Pour It On

John Haberin New York City

Pour, Trudy Benson, Canan Talon, and Abstraction

Go ahead: pour it on.

The nine artists in "Pour" do that and more. For one thing, they combine techniques and media to mine the potential of poured paint. They also look to back color-field painting, when stained canvas for many critics came fraught with lightness and excess. They allow me to start again on my regular gallery tour, with a dozen versions of abstraction's toolbar. Trudy Benson, for one, means that literally, with an illusionism inspired by software as much as history.  Meanwhile Canan Talon, Bob Zoell, Wyatt Kahn, and others rein in the excess, leaving past models as present-day enigmas.

Meanwhile Canan Talon, Bob Zoell, Wyatt Kahn, and others rein in the excess, leaving past models as present-day enigmas.

More than pour

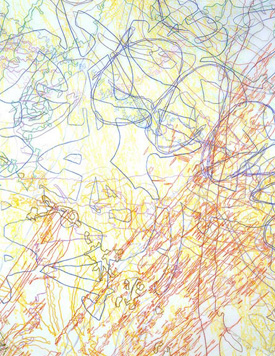

The artists in "Pour" do much more than pour. They also work with lines and traces, like Ingrid Calame in colored pencil as intricate and obsessive as laboratory studies. They work with collage and transfer, like Jackie Saccoccio blending mica into oil or Kris Chatterson with patterns receding into murky perspective. They work with media resistant to stain at all, like Calame or Carrie Yamaoka on reflective Mylar. They leave their mark or its illusion, like thumbprints and color fields for Carrie Moyer or the brush itself for David Reed as the subject of his art. And then they fix those marks in place as pouring never could, like Yamaoka in lacquered slabs.

They do not even look that much like the classic drips and pours of Jackson Pollock and Helen Frankenthaler, and they hardly exhaust the possibilities. Right on opening night in Chelsea, Sofia Maldonaldo elsewhere was spilling so much paint that it landed in the corners of the room as well as on canvas. In "Pour" alone, Angelina Gualdoni recalls the ragged edges of Pollock's black enamel, but in acrylic, and Carolanna Parlato recalls Frankenthaler's fluid primaries. Roland Flexner, though, works in a medium that postwar Americans never knew existed unless maybe they worked as locksmiths, liquid graphite. Moyer even speaks of turning to pours in order to leave painting's history behind. If she ends up associated with precisely the last generation for which a painter's gesture mattered, enjoy the overflow.

They mark a revival of abstraction tempered by allusions and digital media, the kind that led to at least half a dozen coordinated summer group shows in 2011, although not simply a return to the past. Flexner appeared in the 2010 Whitney Biennial, Gualdoni in a 2006 group show called "The Trace of a Trace of a Trace." I have singled out eight of nine before, including two solo shows each for Ingrid Calame and Carrie Moyer. (I guess great minds think alike.) Reed's early oil and alkyd at Max Protech, on a high floor in Soho, was one of those gallery shows that changed everything for me—and I can hardly see the picture of a single brushstroke from James Nares, Mark Sheinkman, or (in video) Anthony McCall without him. And yet, for all that (and I have borrowed the two images here from past reviews), I never thought of these artists together.

Elisabeth Condon and Carol Prusa did, enough to curate the exhibition in a slightly different form for the Schmidt Center Gallery of Florida Atlantic University. (See, if you cannot find a museum in New York, you may yet find the resources, although in smaller spaces three miles apart.) And the artists look so obvious together, to the point that one can have trouble telling them apart.  But alike in what? To ask is to raise the question of what has changed since the 1950s. This is not your parents' (or Clement Greenberg's) color-field painting.

But alike in what? To ask is to raise the question of what has changed since the 1950s. This is not your parents' (or Clement Greenberg's) color-field painting.

For one thing, it represents the shift to other media, starting with thinned acrylic in the 1960s but also with Minimalism's industrial materials. It also points to the breakdown between media. As with Sam Moyer, Scott Lyall, or Jacob Kassay, abstraction draws on photography. Almost all prefer the acid colors of a negative, and Flexner's graphite black looks obviously out of a darkroom. (Carbon is an impressive molecule, even apart from buckyballs.) They can revisit the sincerity of poured paint, but only through the appropriation of the "Pictures generation."

They also move easily between abstraction and representation, as with Calame's organic structures, but also in representing brushwork with or without a brush. Frankenthaler did begin with landscape, as with the breakthrough poured paint of Mountains and Sea, but Flexner's earth is on the scale of geologic time. They also push all-over painting hard enough to squeeze out almost all the bare canvas from Jackson Pollock or Frankenthaler's bare canvas, although Gualdoni uses gaps and concentric black circles to suggest a bursting through. Most of all, though, this is a revisiting of the pour. For these artists, pour it on becomes as much metaphor as medium. It is that eternal dance between presence and absence and then some—that trace of a trace of a trace.

Abstraction's toolbar

I just knew I had seen it all before. I had seen the layers clinging to a painting's surface, the kind that have an artist reaching for a straight edge and a trowel. I had seen the freehand curves and skewed squares, never quite conforming to geometry. I had seen the drips and shadows, some of them even real. I had seen the long trails as if squeezed right out of the tube—and maybe a toothpaste tube at that. I had seen the semicircle, like the keel of a boat sailing across a comic vision of abstraction and out to sea.

It just did not quite register where I had seen it all. Trudy Benson could be running through a brief history of abstraction or a catalogue of abstract painting, as fast as humanly possible. She claims inspiration, though, less in other artists than in Windows Paint and an old Mac SE. Sure enough, her elements have a way of turning up in more than one painting, as if recombined with a mouse click. For the off-kilter squares, typically neutral tones, she might have hit Ctrl-N. She plainly enjoys starting with the most primitive software possible, and (as the dealer notes) she never does find the Undo.

Quite a few artists these days are having trouble with that Undo command. A wave of abstraction is everywhere, less as tribute than as compendium—cutting across media, across imagery, and into quotation. "Pour" insists on real pours, and an older artist at Benson's gallery, James Hyde, has pushed painting more and more into the third dimension, sometimes under glass. Her playfulness makes the most of that dimension, too, with the familiar toolbar of filled circles and freehand curves the mostly thickly painted. She is like Mary Heilmann or Jonathan Lasker with a tablet.

Surely a proper toolbar for abstraction should include rectangles, and a proper fill should include black. For Don Voisine, make that several shades of black. He represents, along with Gary Petersen, a kind of Bushwick Neo-Neo-Geo, where that extra Neo- brings a genuine return from the conceptual to the visual. He still frames a thick black X with colored borders that bring out the color buried within any black. More than ever before, he also allows the overlaps and indentations to create the illusion of mass. If Tony Smith, who began as a painter, had brought his late sculpture to canvas, it might have had this depth of black.

Others, too, are clicking on the recent past. Greg Goldberg approaches stained canvas with thin layers of color, which could have allowed Violeta Maya into the group sa well, while Holton Rower goes for actual pours, sometimes dried on a curved or vibrating surface. Where one artist turns to washes for elegance and economy, the other has in mind excess. Indeed, his gallery calls its larger show "Xstraction," with the accent on extra. Its thirty-nine artists include such performers as Mark Flood and Cory Arcangel, and this is art for an age of market excess. The gallery's director played the same role before for Deitch Projects, and if Jeffrey Deitch turned his usual blind eye to abstraction, it would look like this.

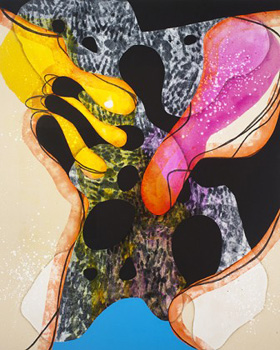

Benson escapes the blindness, but for her, too, the fun comes with a combination of surfeit and familiarity. Her paintings run to maybe four feet on a side. Yet a single panel packs in acrylic, enamel, spray paint, and oil. She recalls another time when abstraction was chafing against its limits, in what Barbara Rose briefly heralded as "abstract illusionism." Rose was writing in 1967 about such formalists as Frank Stella and Jules Olitski, but the term caught on in the 1970s with James Harvard, Michael B. Gallagher, and others now mostly fallen by the wayside. Benson has their painted drips and shadows, 3D doodles, and the illusion of thick tubes created from parallel brushstrokes and alternating highlights. She may be reaching too hard for meaning with supposed references to venus pudica, the classical female figure, but she is hardly alone in wanting to squeeze art history into the computer age.

The enigma of abstraction

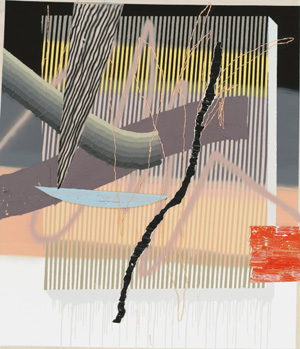

Canan Talon falls just short of familiar—several times over. One could even mistake her for the German master of effacing the familiar, Gerhard Richter and Richter's late work, only which version? Richter has pulled off abstraction, but with a squeegee, and photorealism, but blurred to the very edge of legibility, and one hardly knows which to call more emotionally laden or detached. Talon manages to combine the two tacks in a single painting. She feasts on streaks of black and near monochrome, like Pierre Soulages, but there is no avoiding the subject matter. That just leaves the puzzle of what it is and how it got there.

Talon's industrial landscapes look like silkscreens, although she paints them the hard way. The very repetition of oil tanks and tiered towers, with little or no sign of life, suggests mass production. They even fall roughly into grids, like water towers for Bernd and Hilla Becher. Talon's education has in fact taken her to Germany along with Turkey, London, and Berkeley. Is her urban scene personal or political, and is it lush or bleak? Maybe ask again after seeing it over and over and over.

Scott Treleaven has so much background that I cannot keep track of it all—or, for that matter, see it in his work. Still, he is an obsessive reader and draftsman, and it shows. He also has a predigital medium in mind, with "All-Nite Cinema." A typical painting, on two or three sheets of paper or cardboard, looks like a contact print hastily marked in color for what he has to save, except that the image within the black has already slipped away. Titles allude to subcultures, discoveries, and failures in modern literature and film. Maybe a human body or two went missing along the way.

Someone may have gone missing, too, for Don Gummer. His collages look like jigsaw puzzles, but step back and the puzzle may snap into focus, as a plaza or building—including the Parthenon and a Frank Lloyd Wright dwelling with no one at home. If the torn and cut paper also looks like tiling, this is after all architecture. If it could function as sculptural maquettes, Gummer makes sculpture as well, large and small, with ties to David Smith. And if, in the end, interwoven shades of gray start with the Analytic Cubism of Picasso and Braque, one work depicts a guitar. When it comes to Modernism, abstraction is still playing along.

For Bob Zoell and Wyatt Kahn, painting functions even more like a jigsaw puzzle, and the puzzle may be visual or physical, but never verbal. Zoell bases his compositions on graphic design, effacing the text. The earliest, around 1997, sticks to black and white, with the raw asymmetry of censored documents. When the series mostly ends four years later, it has become clean black bars centered on fields of color. The paint on aluminum no longer looks torn out of the headlines, like censorship in art for David Wojnarowicz and Jenny Holzer. It has gained, however, in both brightness and detachment, like prison bars for Peter Halley or Alex Olson. It is also that much more of a puzzle.

Kahn suppresses the color almost entirely, by binding it like a hit man after a kill. He cuts a wood panel into pieces, covers each piece in colored canvas, and stretches additional white canvas over that. When he puts the pieces back together, never quite snugly, the unseen colors become visible shades of white. Who knew how easy it is to make shaped canvas, and who knew how easy it is for light to penetrate? The edge of one piece may extend to the next, intimating networks cutting across the whole, while the borders of the larger rectangle have taken on gentle curves. It could be the ultimate in white on white, like Minimalism for Robert Ryman. Somehow abstraction is still an enigma wrapped in an enigma.

"Pour" ran at Asya Geisberg and Lesley Heller through May 24, 2013, Sofia Maldonaldo at Magnan Metz through June 1, Trudy Benson at Horton through June 2, Don Voisine at McKenzie through June 9, Greg Goldberg at Stephan Stoyanov through May 31, Holton Rower and "Xstraction" at The Hole through June 20, Canan Talon at Von Lintel through May 25, Scott Treleaven at Invisible-Exports through June 2, Don Gummer at Allegra LaViola through June 1, and Bob Zoell and Wyatt Kahn at Rachel Uffner through June 2.