Abstraction Yet Again

John Haberin New York City

Carrie Moyer and the Recent Past

Anna Leonhardt, R. J. Messineo, and Nathlie Provosty

How often can painting come back from the dead? As often as you like, only then you have to live with it.

That may not sound like much of a burden, especially if the painting is your own, but consider. One nice thing about seeing some of the rising stars of not so long ago, from Carrie Moyer to Sue Williams, is seeing how much they have in common. Taken together, their work looks bigger, brasher, more allusive, and more concerned for squeezing as much as they can into the picture plane. The human presence, especially a woman's presence, is never far off stage.  What, though, does that leave for newer discoveries, from Anna Leonhardt to Nathlie Provosty? The old complaint that "painting is dead" may not go away any time soon, but abstract art can still make the dead newly alive.

What, though, does that leave for newer discoveries, from Anna Leonhardt to Nathlie Provosty? The old complaint that "painting is dead" may not go away any time soon, but abstract art can still make the dead newly alive.

The living dead

It seems only yesterday that abstraction was back, big time, in the hands of a new generation of painters. Thanks to them, it looked different, too, this time out. Critics could complain of "zombie formalism," but at its best it has little space for either zombies or formalism alone. Rather, it has thrived on the collision between the two. Elements of comic strips, photography, collage, and mass reproduction could all enter freely and deceptively—for artists were also putting the burden on you to figure out when they were miming them all in paint. Where Postmodernism had privileged appropriation, as a means of debunking art and culture, it had become just one more element in the mix as well.

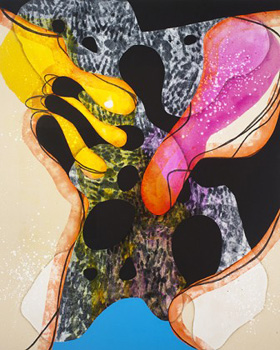

Success being what it is, you can now look for them in classier galleries. Indeed, you may have little choice. You could look for Cecily Brown in Chelsea or Brown in retrospective at the Met, her feverish gestures and quotes from art history given the breadth of a frieze or mural high on the wall. You could head barely a block away for Carrie Moyer. There, too, colors have brightened and contrasts heightened, with large curved or irregular fields framing or layered over splashes, scrapings, and gradations. They suggest a deep or entirely mental space at night. They make it hard to know, in contrast, whether to identify the foreground reds with dreaming or day.

You could head for midtown, for more of Moyer and where Nicole Eisenman was reporting on somewhere at least as trendy and pricy, the Hamptons. Eisenman has typically alternated between mask-like faces and domestic comedy, including a family Seder at the Jewish Museum. That can breed mystery or complacency, and her new drawings and a couple of paintings might have to count as time off from other challenges, but then it was just a brief "Valentine's Day Show." On the Upper East Side, Amy Sillman, too, stuck to "Mostly Drawing," but instead as a fresh challenge. Elements of silkscreen only confuse the layering of paint and print or of gesture and grid that much further. Further uptown, Sue Williams finds a still more luxuriant setting for works from 1988 and 1989.

Does that mean that painting has never looked better—or rather that, once again, painting is dead? Has it moved all too quickly from the Lower East Side to art's equivalent of a funeral home, zombies and corpses intact? Not necessarily. Painters often complain that just a few galleries represent the contemporary artists in museum retrospectives, and they see the power and influence in the hands of big money. It might be better to see money as still playing catch-up ball, snatching artists and estates safe enough to have already found a home in the museum. And the same tendency for artists to move up the food chain means that, inevitably, they take the bait from the higher end of midlevel galleries as well.

That could simply confirm the importance of the wide range of galleries between collectives and big money. Dealers who lose artists can play a continued role by adding anew to their depleted roster, even if they deserve to cash in. In turn, a slightly posher realm can give artists more space, more attention, and maybe even more freedom. They can also put the changes in perspective, and the new shows are also learning opportunities. Williams still sneaks flowers, animals, and body parts into abstract swirls, but she seems halfway prurient after all. She marks something of a transition, just as artists were learning how to bridge styles and media as new ways to get "in your face."

The breaking of boundaries can be another dead end, if anything goes means only that the market rules. Yet it has also meant the needed tools to get over the very dichotomies that had threatened painting, like geometry versus gesture. Collage, popular culture, or the mere appearance of both in paint has played a similar role for excluded voices, such as African Americans after Romare Bearden, and it is no coincidence that every painter that I have mentioned thus far is a woman. There are still plenty of retreads of Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism, some of them interesting. There are still, too, plenty of reasons for fear or despair. For a moment, though, consolidation has not looked all that bad.

Dead heat

What does that leave for others now? Do they, too, hang together, or are they already back to old choices of gesture, geometry, and slapdash representation? If they look familiar enough, is that boring, and if anything goes, who gets to decide what gets left out? If I face this dilemma every, say, six months, is that just my usual complacency when it comes to abstract painting? Probably, but a few more artists suggest the possibilities, all on the Lower East Side. Naturally enough, they are all in their way looking back.

Anna Leonhardt looks back most obviously to the choice between Minimalism and expressionism. Her lightness of touch has something of early Philip Guston—which, be it duly noted, already bordered on complacency, enough that Guston abandoned all-over painting soon enough for the cartoon angst that one remembers today. Yet she also has a tactile quality closer to Hans Hofmann, with a gob of paint sticking to each canvas.  She might have deposited it as a signature or an afterthought, but the contrast of shimmer and extrusion defines a style. It also defies expectations, for Leonhardt may apply both fields with a palette knife as well as a brush. They become a record of process and signs of painting itself.

She might have deposited it as a signature or an afterthought, but the contrast of shimmer and extrusion defines a style. It also defies expectations, for Leonhardt may apply both fields with a palette knife as well as a brush. They become a record of process and signs of painting itself.

Alejandro Ospina looks back further still, to the origins of abstraction. Small areas of color and mere squiggles scoot across as in the late harder edges of Wassily Kandinsky. They look back to when painting was very much in the air. Yet they, too, have associations closer to the present—and to the choice between pop culture and purity. Ospina claims to have adapted architectural drawings and titles many of the works Supergirl. He calls the show "Cryptomnesia," meaning memories that one mistakes for original thoughts, but then how could he name his sources? The results are trendy, fun, knowing, and sure enough familiar.

R. J. Messineo trades on familiarity, too—all the more so by making the familiar difficult to acknowledge. She looks to a choice as well, between representation and abstraction. (This is, after all, the gallery that first presented Katherine Bernhardt and Moyer.) Her scenes may look like abandoned studio interiors, cabins in the woods, or New York buildings at night from across the street. They are difficult to penetrate, with the most recognizable objects in the background. Collage elements like dismembered stretchers or frames take them that much further into depth, while the brightest marks tend to lie in the picture plane, often as small strokes that make the larger ones beneath them appear to have broken up as the brush dragged them across.

Nathlie Provosty does even more to bridge past and present. Her tall abstractions move among shades of black, white, or a single color. Their slowly unfolding monochrome looks back to Ad Reinhardt or Minimalism, but contrasting areas of matte and high sheen are at home in mixed media today. Those curved areas may look back to Henri Matisse as well, pressed against a painting's edge like the leg and torso of a grand nude—even as that very edge takes on a touch of bare canvas that seems to change its dimensions and to divide a painting into two slightly misaligned panels. Add in the show's punning but near meaningless title, "My Pupil Is an Anvil," and a press release is begging to be written. For all their gamesmanship, though, there is no getting around their outsize ambition and allure.

These, then, are the choices, for now. They could serve as proof that the decisive moment of artists last time is already past, but then what could be more trendy than to claim a trend that lasted only five or fifteen years? They may not be uniformly super, not even Supergirl, but then could painting's love affair with cartoons and anime have faded already as well? Not likely, but one can always hope. Enjoy painting while you can. Before you know it, it will have died once more and returned from the dead.

The next challenge

In reviewing here some terrific shows, I had to ask: are they the ultimate rejoinder to skeptics? Are they fully alive? You know where I stand, but I had to say it. Then again, you might complain, is the whole frame itself a zombie that was never alive but, against all odds, no one can kill? Let me append a few thoughts on why we have to hear that again.

So is that it, then? Has "painting is dead" become a dead letter? It may seem that way, if only because we have heard it so many times. It must sound like just another complaint that people no longer talk to one another, thanks to television, computers, and now smartphones—or even Groundhog Day. Still, the phrase is not just a timeless, empty litany: it has a history worth remembering.

It was often declared in response to new media. Paul Delaroche coined it in his awed reaction to photography, as I noted in covering Ethan Greenbaum, and it lies behind Dada. Besides new media, though, their rallying cries turn on something else: they were aspirational rather than factual, since they challenged the dominance of painting. They need not have believed that they could ever succeed. Much of their best work, including that of Man Ray and even at times Marcel Duchamp with their haunting surfaces and assemblage, actually filled the creative role of painting, only in other media.

By the 1970s, that dominance had become less real, thanks to conceptual art and more. Yet it was also more dogmatic, thanks to Clement Greenberg, the beatification of Frank Stella at MoMA, and schools. Many graduating college then would have known and admired painters like Michael Goldberg. Even more, they wanted to be the next Stella. The big news just ahead upset the formalist creed, but it also elevated painting. That includes the Neo-Expressionism of Georg Baselitz and Julian Schnabel, but also the likes of Eric Fischl and David Salle.

I was not writing then, so I can only mention my start in the 1990s. Yet it is not just my story, for something had changed entirely. After critical theory and the "Pictures generation," painters were no longer defending the canon: they were beleaguered survivors. I had to go to Snug Harbor on Staten Island to see them, for my first entry into the debate. Now to deny that painting is dead was itself an aspiration. And now, in yet another phase, the comeback is itself a new dogma—enough to raise a fresh challenge to the work of art.

That challenge could take many forms, not least having to live as one medium among equals. It includes the challenge of having to prove one's worth, when art has seen so much before. It includes, too, the challenge of living without an avant-garde. If anything goes, what matters? And how does that differ from the public's dismissal of art as "anyone can do that"? Maybe one needs critics after all, to remind people of how much work like this takes—and to embrace, whenever it comes, the next challenge.

Cecily Brown ran at Paula Cooper through December 2, 2017. Carrie Moyer ran at D. C. Moore through March 22, 2018, and at Mary Boone through April 21, Nicole Eisenman at Anton Kern through February 24, Amy Sillman at Gladstone through March 3, Sue Williams at Skarstedt through April 21, Anna Leonhardt at Marc Straus through February 9, Alejandro Ospina at Johannes Vogt through March 24, R. J. Messineo at Canada through April 8, and Nathlie Provosty at Nathalie Karg through April 15.