Painting and . . .

John Haberin New York City

Lily Ludlow, Trisha Brown, Sam Moyer, and ". . ."

Someone writing in the 1960s would have had a hard time not returning again and again to abstraction. It was not just everywhere—assuming that a still relatively small gallery scene and uncomprehending public count as everywhere. It was everywhere in artists' heads. It was dominant. It was the canon. It was a paradigm.

I missed all that, but now I have an even harder time not returning to abstraction, but for a different reason entirely—a newfound diversity. It can slip in an instant between gesture and geometry, rigor and impulse, high and low, or parody and sincerity. It can begin or end as painting or photography, old or new media, and even representation. With Lily Ludlow, a canvas shares space with fashion and design. With Trisha Brown, it extends the collective movements of dance and performance. With Scott Reeder, Sam Moyer, Kadar Brock, and Matt Jones in ". . .," it erases itself.

Once everyone knew quite well what abstraction was, and once everyone knew quite well that it was dead. Of course, there was a time in between, with labels like "New Image painting," and that label might apply now. It is a good reminder of another recurring theme of this site: when people complain about pricey installations at the expense of painting, they are flogging a dead horse. Painting is getting along just fine, thank you. It just may or may not be painting.

It also is not simply turning back the clock, to what a show at MoMA calls "the forever now." Postmodernism has been very hard on the claims with which I started, about canons and paradigms. And now that Postmodernism itself can sound downright dogmatic, abstraction can start to look past those claims, at recent history. In the 1960s, it flourished alongside Pop Art, Minimalism, and earthworks—and even Jackson Pollock or William de Kooning was not always so abstract after all. Ludlow's tailor shop recalls an older, more comforting, and yet also more confining Lower East Side, but also a combine painting by Robert Rauschenberg. Brown has always lived on the edge of late Modernism.

The artists in ". . ." are still haunted by its ghosts. Not so much by the ghosts of abstraction past, although they will surely haunt the viewer, much as for Alix Le Méléder today. Who left so many thin traces and dense weaves? Who left several decades if art obsessed with poured paint and spatters, geometry and randomness, gaudy colors and absence of color, inscrutable layers and scarred canvas, abstraction and excess? Ghosts being what they are, I must leave it to you to provide the names. With an exhibition title like this one, something must go unsaid, and someone must connect the dots.

Old-fashioned new images

Lily Ludlow might have turned her dealer into a tailor or dress shop from nearly a century ago. It only makes sense so close to Orchard Street—or, fittingly enough, Ludlow Street. So what if now one can buy mostly cheap socks and expensive art? So what if the space now nestles instead between offices in Chinatown? So what if Lower East Side fashion consciousness has taken on a whole new meaning? One still has memories.

She includes at least one mannequin, although it wears just an unflattering white top more suited to a hospital. It also stands precariously on wheeled pieces of wood, as if unwilling to stand still and not quite ready for rollerblading. A rough-hewn slab in place of legs serves as another's brutal pedestal, a strange white mass as its "fish head." She derives her more delicate arms from a fancy chair and her curves from a table leg, the kind that Sherrie Levine gives to a pool table after Man Ray. An old-fashioned chair sits empty nearby, untouched but for a lightly stained seat cushion. I would not have dared sit in it anyway. Call it art or design, Dada or Surrealism, combine painting or period room, history or the present.

She includes at least one mannequin, although it wears just an unflattering white top more suited to a hospital. It also stands precariously on wheeled pieces of wood, as if unwilling to stand still and not quite ready for rollerblading. A rough-hewn slab in place of legs serves as another's brutal pedestal, a strange white mass as its "fish head." She derives her more delicate arms from a fancy chair and her curves from a table leg, the kind that Sherrie Levine gives to a pool table after Man Ray. An old-fashioned chair sits empty nearby, untouched but for a lightly stained seat cushion. I would not have dared sit in it anyway. Call it art or design, Dada or Surrealism, combine painting or period room, history or the present.

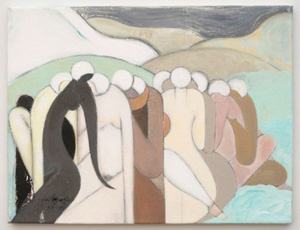

So do Ludlow's paintings, but they are also more interesting. The show's title, "Ten for Aidas," puts them front and center, although I would not give up their context in madness, fashion, and history. They, too, depict women, in spare curves of graphite and acrylic. Their short, perhaps bobbed hair would look just right on flappers. The soft, mostly light colors and all-over compositions would fit just fine amid the murals of Rockefeller Center. The darker reddish-browns might come from the mannequins.

In groups women nurture one another or vanish together into an art deco dreamscape. Alone, and more recently, their tapering curves double back on themselves like swans, but more in sleep than in pain. One simply bends her head atop the long cylinder of a neck. At least one nude's hair covers her face, but most appear from the back, that much more stylized and sculptural. Rubbing gives the acrylic texture and lightness, but also the thicker look of tempera on gesso. They appear to have been around a while, if only in memory.

One knows this terrain not only from an earlier America. The space between abstraction and imagery is all over the place right now, much of it firm in its outlines but fluid, sketchy, and painterly in detail. Carrie Moyer at the same gallery occupied that terrain only a month before. Many practitioners are women, like Amy Sillman, Ethel Lebenkoff, or Jennifer Wynne Reeves—in counterpoise to another kind of fashion, for macho installations. Perhaps it all goes back to that "new image" painting of the 1970s, like Susan Rothenberg. Still, this new new imagery is less iconic and more personal.

For more of the connection to women and to the past, it is hard to top "Eva Zeisel at 105." Zeisel's furniture and ceramics reflect more than her experience with the Bauhaus. A vase from the 1930s adopts its pattern from Piet Mondrian, ewers from the late 1950s have the coarse curves and geometry of early Modernism's "primitive discourse," and Vienna leaves its traces everywhere as well. When rows and rows of objects assemble on the floor, packed more tightly than in any showroom, something else happens, too. The space between art and design finds a physical place before one's eyes.

Dance class

It makes sense somehow to think of a dancer as a visual artist—and some in the early twentieth century who went about inventing abstraction surely did. It suggests the affinity of modern dance with performance art, both so often silent except perhaps for music. Make that often plotless as well. It gives new meaning to that old phrase for sculptors like David Smith and Alexander Calder, drawing in space. It captures the tricky qualities of some great painting—the tactile and the visual. And that combination surely applies to Trisha Brown, a dancer who can make one think of works on paper as painting or as choreography.

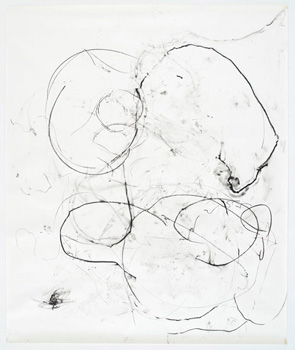

And I mean large works on paper. They stretch nearly eleven feet tall and wider than a human body. Identification with the body only grows, too, the more time one spends with them. Most sheets have a vertical format, like a person standing. Step back from the spare black marks, and hints of a figure or two appear—perhaps to vanish and then to appear again. One could be crouching, an arm raised high to pierce the air. Others could have backs, breasts, or buttocks thrust forward, and I could swear that I made out two faces kissing amid the swirl of black.

If one has any doubts, a back room has a video of, lo and behold, dancers. They move slowly and portentously but fluidly and constantly. They may touch, but barely, as if to insist not so much on communication or mutual desire as solitude and sensation. On paper, bodily sensation arises from texture, too. The sole small work, by the entrance, introduces the vocabulary of smudges and traces. Brown uses graphite and oil pastel, the lines close to breaking apart as she stretches or presses them across the the white expanse of paper.

Historically, seemingly opposed terms like tactile and visual have often described art its most classical. Giotto gave the Renaissance what Bernard Berenson called "tactile values," but also a formal and visual unity. The sculptural form and symmetry of High Renaissance painting seemed their logical extension. The opposition returned with a vengeance in late Modernism, in calls from Clement Greenberg for "flatness" and Harold Rosenberg's for "action painting." These critics wanted "pure painting," but also an extension of the living and breathing painter. One can picture Jackson Pollock circling a drip painting as a dance.

In fact, Brown's designs, all from 2002 and 2003, look like nothing so much as late Pollock, when the canvas all but emptied out, color vanished, and the human figure almost emerged. A painter of Pollock's time only wished that he had sheets of paper this large and, compared to stretched canvas, this close to the wall. Her ten large drawings are not identical in size, but they can easily look it, and they make the gallery a kind of theater. Yet Brown is of quite another generation than, say, Alvin Ailey, a postmodern dancer born in 1936 who collaborated with Robert Rauschenberg. Perhaps one should picture the collective dance rather than Pollock's brooding loner. Perhaps one should sense the visual comedy of Pop Art—or those diagrams for where to place one's feet in dance class (already the subject of a "performances score" for Clifford Owens).

Perhaps, but if anything she trumps Pollock's high seriousness and detachment, but without the high tension. How can you know the dancer from the dance—especially when neither is smiling? It may say something that the show looks bland and arbitrary in jpg rather than in person. Now, people long disdained Pollock's late retreat from abstraction, too, not to mention the sweeping gestures of a late de Kooning, which these works also resemble a bit. For all three, though, the tactile values are there all the same, and (come to think of it) late Pollock and Willem de Kooning are looking better all the time. Maybe one can start to see them, too, as postmodern.

The ghosts of abstraction

Scott Reeder, Sam Moyer, Kadar Brock, and Matt Jones seem haunted mostly by themselves. The work in ". . ." all comes with a history, of choices gone terribly wrong, some made more and more explicit and some effaced or destroyed. Reeder's even look like ghosts—or at least photograms. The largest, in black and white, is the densest and ghostliest. Others, only slightly smaller and in pale shades, focus on the building blocks of circles, cylinders, or lines. The actual technique, akin to frottage, combines painterly gesture and the absence of the thing painted over.

Moyer's could pass for negatives in the trend toward photography as object, too, or for more of Reeder's. The elements, though, more closely follow the grid—and then warp it. She also has the show's only hint of representation, for the wrinkled geometry of fabric settles into the illusion of film, akin to painted fabric by Helene Appel. Black, bleached, and ironed flat, it redoubles and distorts the traditional translucency of oil and the opacity of canvas. And where she at once manifests and hides the flat surface, Brock does everything he can to expose it. He abrades his paintings to the point of gaping holes, which in turn could pass for the deepest colors.

Moyer's could pass for negatives in the trend toward photography as object, too, or for more of Reeder's. The elements, though, more closely follow the grid—and then warp it. She also has the show's only hint of representation, for the wrinkled geometry of fabric settles into the illusion of film, akin to painted fabric by Helene Appel. Black, bleached, and ironed flat, it redoubles and distorts the traditional translucency of oil and the opacity of canvas. And where she at once manifests and hides the flat surface, Brock does everything he can to expose it. He abrades his paintings to the point of gaping holes, which in turn could pass for the deepest colors.

One may still insist that Moyer has photographed the results, faced with the overwhelming interplay between forms and media. In her solo show not long after, "Slack Tide," I kept looking in vain for irrefutable traces of a third dimension—proof that, as René Magritte never did say in Magritte's Surrealist years, This is not a photograph. All I had for evidence was the occasional tear or extra strip, in contrast to Tom Burr's folded and tacked blankets and shirts shorn of creature comforts. All I had, in short, was a room of electric black and white. Could Sam Moyer be lying after all? I doubt it, but so much for the truth in painting.

If all-over painting demands geometric rigor and total immersion, Jones carries it one step further. Along with three large paintings, one to a wall, a fourth points down, suspended from the tidy rectangle of a fluorescent light fixture. The thick white spots on pitch black look like star maps, but the black effaces earlier fields of intense color. Up close, one can see color within the spots, almost like making eye contact. Once one catches on and steps back, an entire canvas takes on shades. And then the show has a fifth body of work in actual bursts of color, by one of the four artists, but I had better not reveal the ending of this ghost story.

As for the artists' hauntings, everyone has something to hide. Reeder painted over pasta, which somehow gets him longing for Arte Povera rather than Pollock and abstraction's past, Mark Sheinkman, or a really good dinner. Brock and Jones say that they attacked finished paintings in fits of and anger. Like most genre fiction, these stories may sound canned. Who knew there was such anger out there, and who knew that disappointment and despair could produce such gargantuan projects? The gallery defends itself against the label "self-consciously 'clever' "—another way of saying that some ghosts deserve a rest.

Reeder's smoke and mirrors make me think, say, of Cy Twombly, who just happens to have died last year. Moyer simply takes care to distinguish her manifestations of canvas itself from the deep space of color-field painting. Never mind that Morris Louis in his Veils did more than anyone to identify color and image with the thing itself, while she is the one trading in illusion. Never mind, too, the filmy black and white. Still, the show understands the slippage between conceptual art and abstraction everywhere these days. And the combination of physical presences and optical activity is positively haunting.

Lily Ludlow ran at Canada through December 4, 2011. Eva Zeisel ran at Schroeder Romero & Shredder through January 7, 2012, Trisha Brown at Sikkema Jenkins through January 25, ". . ." at The Hole through February 4, and Sam Moyer at Rachel Uffner through April 22.