Realism as Reckoning

John Haberin New York City

Bradley McCallum and James White

Alejandro Campins and Melanie Vote

Realism in art has taken a beating. Who would settle for it, so long after abstraction and conceptual art, and who still trusts in representation or the truth? Could the hard edge of photorealism stand for truth—or an artifice and death?

Some artists, though, demand a reckoning. They seek it in politics, culture, or within, and they locate it in the very artifice of realism. For Bradley McCallum, photorealism conveys the horrors of genocide with the chill of a photographic negative. With James White and Alejandro Campins, one can turn from painting to painting and style to style in hope of an escape.  And Melanie Vote puts those possibilities to the test in a single show, to imagine death in her own person. By then realism has given way to an installation and a dream.

And Melanie Vote puts those possibilities to the test in a single show, to imagine death in her own person. By then realism has given way to an installation and a dream.

Painting with impunity

Bradley McCallum paints with impunity. At least he calls his latest series "Impunity," and it is punishing. Each subject is a war criminal, from some of the most horrific acts of recent memory, from Africa to the killing fields of Cambodia. One with loose hair, from the former Yugoslavia, even went by the name of the Butcher. The men are all the more terrifying for that decorum. It could stand for indifference to human life, but they wear their suits and ties because they are on trial for crimes against humanity. The artist is concerned for remembering and the truth.

McCallum supplies each man's name, where he stood trial, and the source of the photograph from which each painting began. If each indeed wears a dark suit and tie, perhaps the most frightening of all makes it difficult to be sure. Like the others, he leans forward, pressing up against the picture plane. His forehead alone, beneath a receding hairline, takes up almost half the picture. His hands, clasped tightly to his mouth and obscuring his tie, take up much of the rest. Even at rest and wearing a wedding band, they could be about to deliver a knockout punch.

That leaves only his broad nose and eyes, for McCallum crops his faces tightly, right to the tops of their heads. This man's ears up against the left and right edges allow no space for anyone to breathe. They only emphasize his brooding pose and fearful symmetry. The white glare of his eyes stands out against the dark background and his black skin. They are aimed at you. Their very stillness becomes a refusal to go away.

One can turn to adjacent portraits for a more comforting presence, but it will not come easily. Another man wears glasses, which one can choose at one's peril to associate with book learning or introspection. A third has a thin face and that loose hair. Still, they, too, will not turn away. Besides, they have the ghostly presence of a photographic negative—their suits, mouths, and wide eyes an electric white. So, for that matter, does a second portrait of the first man, right by his side.

The demand for truth may explain their photorealism a little too easily. McCallum converts each image into its negative, with a filter in Photoshop, before rendering both by hand in oil on linen. He closely pairs the two in a series of small paintings, where the color image feels almost comforting by comparison and the ghostlier image a testimony to the lives that can now return only as ghosts. They loom equally nasty and more effective in separate larger canvases. The pairs will travel to the Hague, where many of the men stood trial, and then to countries where atrocities took place. People there are unlikely to have forgotten.

Photorealism almost always has its creepy overtones, a fact exploited by Gerhard Richter with German terrorists and Philip Pearlstein with his Neo-Mannerist poses and less than sexual nudes. It also has its documentary side, much like photographs of war for Bettina WitteVeen. A second series adopts an oval format, like an antique mirror, to ask Americans to see their reflection in how the world goes. Here McCallum excerpts from protests abroad that culminated in the burning of the American flag, so that one sees little more than the flames. It presents a one-sided view, no doubt, of blame for events today, and it may well run counter to the purpose of trials for war crimes—to bring not just justice, but also closure. And yet the images are impossible to forget.

Time lapse

With James White and Alejandro Campins, one could breathe a sigh of relief at turning from one to the other. It hardly matters where one begins. No wonder they get along so well together. White calls his series "Aspect Ratio," after the dimensions of a monitor or picture tube, to invoke an image at a digital divide from experience, but Campins has all the more invested in the ratio of width to height. Campins calls his "Lapse," but White is at least as obsessed with visible signs of neglect and with measuring out time down to the second. Both can claim to a stark realism.

White's sophistication and photorealism may have the more obvious claim, while Campins has a greater claim to paint itself. For both, though, surfaces are designed to draw one in and to keep one out. White works strictly in black and white, while Campins adopts soft colors in enamel and oil, with a dark yellow or pale gray set against the blue or green of fading skies. Both, though, avoid the full range of color associated with natural light and realist traditions, and both occupy the long wee hours of the night. White sticks to close-ups of confined spaces, like kitchen counters and doors just barely ajar behind a deadbolt and chain, while Campins can never bridge the distance across near empty space. Both, though, are describing barriers to escape or entry.

White's sophistication and photorealism may have the more obvious claim, while Campins has a greater claim to paint itself. For both, though, surfaces are designed to draw one in and to keep one out. White works strictly in black and white, while Campins adopts soft colors in enamel and oil, with a dark yellow or pale gray set against the blue or green of fading skies. Both, though, avoid the full range of color associated with natural light and realist traditions, and both occupy the long wee hours of the night. White sticks to close-ups of confined spaces, like kitchen counters and doors just barely ajar behind a deadbolt and chain, while Campins can never bridge the distance across near empty space. Both, though, are describing barriers to escape or entry.

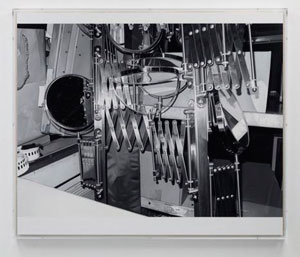

White, in England, could have one looking twice to confirm that this is painting. His varnished aluminum and acrylic sheets, set in Perspex boxes, have the feel of film all by themselves. His subjects, too, lean heavily to the sheen of metal and plastic. Keys lie abandoned and plastic bottles stand open. Plastic or foil sheets have fallen to the floor. Up close, they dissolve into their ghostly highlights.

Someone has stayed up way too long, and someone else is looking way too soon. Photography has become the gold standard, or maybe acetate standard, for realism, but White insists on how much it turns against nature. Anyone who has tried to photograph a tall building only to have it tilt backward should know. He prefers odd angles and cut-off edges. When he paints a sink and bathroom mirror, the twinned images are uncomfortably close to each other and to you, and elsewhere the tap is still running. Time may be running out.

Campins has a smaller room off to the side. His subjects stand at a greater distance, but with a greater intimacy. Their mute colors, awkward shapes, and almost waxy textures have much in common with abstractions from the 1990s by Ilse d'Hollander, a Belgian artist often compared to Raoul de Keyser, at the same gallery a month before. One wants to linger longer. Downstairs, the dimensions, drama, and departure from the square grow considerably, in wide-format paintings of much the same. Angled walls and roads have an intuitive rather than mathematical perspective behind a final spattering of paint, enfolding the viewer even while standing for barriers and distances difficult to cross.

They are also cryptic. The concrete could belong to monuments or prisons, in states of abandonment or still under construction after decades of false starts. Since this is Cuban art, as for Yoan Capote, Juan Francisco Elso, and Belkis Ayón, one can fairly say that the choices amount to much the same thing. Titles help, but no matter. The broad pylon supporting a nonexistent highway and a bunker defending nothing have become suspended in time. For these artists, the night weighs most heavily of all.

Out of the air

If you are on her mailing list, you may know Melanie Vote first from a mere detail. If it has you dying for more, it may have her dying as well. It shows a woman on her back, flowers in her nearly clasped hands, against an elaborate tiling. Its photorealism has the impersonality of Rackstraw Downes or Rudolf Stingel—from its porcelain finish to the shadows that stain her flesh. Yet it shows her from only just below her shoulders to above her knees. A stalk of greenery bends down under its own weight to just past the edge, as if it, too, were cut off from life.

Who is she, and is she dead or alive? The floral arrangement, rich enough for a funeral, is well past its prime. The blue and white tiling brings out the deathly shadows in her white dress. In the painting as a whole, her eyelids are shut, in sleep or a last rite, but her hair runs wild like a harridan's or a ghost's. Her placement breaks the mosaic's symmetry, adding a further disturbance. Her white dress billows out like a ballerina's, and her toes turn down as if in a dance.

She titles the painting Place like Home, but is there no place like home? Vote is her only model, and a smaller painting has her as a child, in the clothing and sepia tones of a photograph from long ago. Pretend wallpaper on the gallery's walls extends its old-fashioned interior, while an actual child's bed across from it picks up the larger painting. It holds flowers, but a missing body. There the stuffing torn from a comforter might stand for mold or old bones. They, too, could be hers.

"Will you walk out of the air, my lord?" Polonius asks, and Hamlet, as always, has a further question. "Into my grave?" Vote paints herself in and out of the grave, in search of life. She calls the show "Overgrowth," and overgrowth takes time. She says that she had on her mind her mother's death, with its burden of the past.

A third and larger painting delves further into past and present. She speaks both literally and figuratively when she calls it Excavation of Life and Death. The excavation of family and self reaches to art, including competing styles of realism. This one has the fresher look of plein-air painting, out of the air. It also contains a naked body, turned down once again to hide her face. Like photos by Cindy Sherman, it could represent an archaeological excavation, a crime scene, or a grave.

The body lies outdoors in a shallow pit framed by wood, to keep it from caving in, and a carpet of large colored circles. They are one part Larry Poons and at least two parts Twister. The painting also faces a small corner piece of dirt and a shovel, like an earthwork by Walter de Maria without his Minimalism or by Robert Smithson without his mirrors. The installation takes her out of the grave and ambiguously into life. "You do me wrong," Lear says, "to take me out o'th'grave." If you are old enough to remember a game of Twister, you are already looking past the tragedy and stretching your limbs for the game.

Bradley McCallum ran at Robert Blumenthal through March 5, 2016, James White and Alejandro Campins at Sean Kelly through March 12, 2016, Ilse d'Hollander through February 6, and Melanie Vote at Hionas through April 16.