Richter After Richter

John Haberin New York City

Gerhard Richter: Painting After All and STRIPS

Gerhard Richter is looking back—at his life, at his nation's history, and at his art. And why not? Who else has done more to test the limits, the possibilities, and the very nature of art?

Besides, he has been looking back all along. "Painting After All" presents him as an older artist still testing his own limits. It emphasizes the conceptual side of an accomplished realist and abstract painter, and it brings out the melancholy in an artist who can still knock you off your feet. Born in 1932 in Dresden, Richter had already had quite a career by the time of a MoMA retrospective in 2002. That show had twice as many works as the Met Breuer now. They included riffs on Pop Art and other early work that he might just as soon forget.

One might think of the new retrospective as picking up where the first left off, with later work and a critical agenda with no room for mere beauty or sentiment. For all that, they will not vanish any time soon. (I can only ask that you follow the link to my earlier review, where I asked why.) Just eight years ago, in fact, Richter already knocked me off my feet, with a foray into digital art, the STRIPS. As ever, as he looks back on art, he repeats his own history. He sustains the present by a battle with the past that brings its strategies newly alive.

A deeper history?

This is and is not a retrospective. Gerhard Richter gets two full floors of the Met Breuer in its last show before turning over the building to the Frick Madison, for more than a hundred works. Wall text spells out his origins in East Germany and his insistence on destroying work from those years. One can only speculate at how an enforced social realism nonetheless informs all his art—from his skilled realism based on photos to the uncanny blur and continued questioning of his series based on the Baader-Meinhof gang. Still, the show's heart is abstraction from the new millennium, including full series, some never seen before in the United States. It selects from older art to put newer art in context.

It starts by laying out the possibilities. One room has approaches to abstraction, one more stunning than the next. Flow from 2013 has the sheen of poured paint on aluminum. 4,900 Colors from 2007 fills a wall with five big panels. It looks back to his first foray into algorithms and color, his Color Charts from 1966. The room has space, too, for denser, crustier colors right out of Willem de Kooning—and for tools that may encourage or preclude expression, including a brush and a squeegee.

An adjacent room has Richter as a realist with a complicated family history. He paints his wife in awkward but determined poses while going through a divorce, and he gives a daughter the complexion of a marionette. Laurie Simmons has nothing on this. Another room takes art history as his "Atlas"—including cloud studies out of John Constable and seas out of Caspar David Friedrich. One last room has a still deeper family history, just as Nina Katchadourian curates hers, with Uncle Rudi in uniform from 1965. Next to a portrait of a Nazi mass murderer from the same year and a panorama of the Alps, it becomes Germany's dark history as well.

With the possibilities in hand, the floor below turns to the series, particularly recent series. Here abstract painting wins out, on a titanic scale. Does Richter leave nothing to chance? Cage from 2006 pays tribute to John Cage, whose music thrives on chance procedures, but does it leave him trapped? Or does his turn almost exclusively to abstraction relieve him of a burdensome history? Forest from 2005 connects the space of pure painting to dark woods and Nazi elevation of the earth, while Birkenau from 2014 began with archival photos of the death camp.

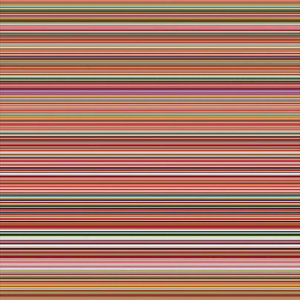

Can the crusty surfaces efface that history? Richter has yet to efface his own, if not for lack of trying. Technology only extends the conflicts and the possibilities. A mural painting of the Elbe from 1957 that he was sure had disappeared surfaced in Dresden in 2008. He photographed them, smeared the photos with ink, and converted the results to inkjet prints. The single largest panel digitizes his painted colors as horizontal stripes.

One last room returns to the tension between abstraction and figuration. His seascapes grew colder after a trip to Greenland in 1972, but his third wife and their child reflect a new tenderness in 1995. Never mind the blur in black and white. Smears and blurs at once heighten and efface his colors as well. Abstractions from 2009 bury photographic images in white. One can take either floor in the opposite direction, but the narrative will never run only one way.

Resurgence and modesty

The resurgent abstraction offers hope, and so does the show's punning title. Richter is still painting, after all. At the same time, he is painting despite it all—despite his past, Modernism's pasts, and the terrors of the last century. The curators, Sheena Wagstaff and Benjamin Buchloh with Brinda Kumar, refuse to shy away from the worst. As a veteran with Rosalind E. Krauss and Hal Foster of October magazine, Buchloh necessarily inclines to "theory." One can see it in the show's lack of chronology and often puzzling groupings.

One can see it, too, in the inclusion of conceptual art and sculpture. One floor opens with eleven panes of glass leaning against each other and the wall, the next floor with an ordinary framed mirror. A larger grey mirror shares a room for abstract paintings. Richter had his first four panes of glass in 1967, rotating at angles as if to let in the air. They also play on the Large Glass of Marcel Duchamp. Here, though, there is no getting around the refusal of a mirror or window onto nature.

One can see it, too, in the inclusion of conceptual art and sculpture. One floor opens with eleven panes of glass leaning against each other and the wall, the next floor with an ordinary framed mirror. A larger grey mirror shares a room for abstract paintings. Richter had his first four panes of glass in 1967, rotating at angles as if to let in the air. They also play on the Large Glass of Marcel Duchamp. Here, though, there is no getting around the refusal of a mirror or window onto nature.

One can see "theory," too, in the show's distrust of beauty and refusal of sentiment. Back at MoMA in 2002, Richter all but dared a critic to apologize for both. I lingered over a glowing portrait of his wife reading, and Uncle Rudi had me noticing most his foolish grin. Now every moment of joy ends in melancholy. Cathedral Corner from 1987 delights in sunlight and dappled leaves, but then come the frozen seas after Friedrich's The Wreck of Hope. A small monochrome sneaks into the family history, as Blood Red.

Other works turn more explicitly to death. A city from above, the museum explains, refers to Allied and Nazi preparations for bombardment. Art itself, it claims, is in league with annihilation. Who knew? A blurred human skull hangs next to Cage. The impending death is now Richter's and a generation's.

Then again, maybe it is harder and harder for him to confront death. He had not meant those photographs of Birkenau to end in abstraction. He just gave up on representing them. Then, too, maybe abstraction won out because his aging hand can no longer produce such precise and haunting realism. Not that he has given up on strong feelings. He is just honest enough to let them show.

That modesty only adds to the power of Richter's large works and skilled images, continuing to this day. One last sculpture, House of Cards, dates to 2020. It plays on a similar arrangement by Richard Serra, but in glass rather than rusted steel. It places Richter in a line from Minimalism to Postmodernism, rather than from Pop Art and epic abstraction, but it is not imposing on anyone. It may fall to the ground and shatter, just as photorealism here cannot escape the blur. When it comes, the crash should truly knock you off your feet.

Reeling in Richter

Can Op Art have you reeling? Richter sure can. His STRIPS have me reeling in color, in paintings as much as six feet tall and nearly twenty feet across. I was reeling in patterns, an untold number of them, made from more than eight thousand striations running the full length of a painting. They have me reeling in a lame effort to understand them—everything from the medium to the process to the mirrorings and divisions. Besides, up close at his Chelsea gallery I truly was reeling, to the point of sucking in my breath to keep from falling and to overcome the feeling in my stomach.

It may not sound like a compliment: this art makes me sick. But I was speaking figuratively when I said that about the STRIPS (I think), and no one does more to take art's metaphors apart than Richter. No one else has a way of pushing virtuosity to the point of banality and banality to the point of virtuosity. No one else, too, has long moved so easily between photorealism and abstraction—or between versions of abstraction based on the artist's hand and on color charts, long before dark color wheels for John Mendelsohn. And sure, put all those together and one has a decent working definition of Op Art on steroids.

Make that digital steroids. Even after Op Art's inclusion in "Ghosts in the Machine" at the New Museum, it seems hopelessly low tech and obsessed by illusion. Richter started, cleverly enough, at the opposite extreme. He began with one of his squeegee paintings from 1990, a series made by hand by dragging across a largely gray surface. The immersive variations in color and texture more or less took care of themselves. Then he digitally sliced, diced, and mirrored it, until he had by his count four thousand new patterns, an apparent regularity, and a whole series of entirely unique prints.

For the technically inclined, he folded the original over itself, joining mirrored halves. Then he repeated that mirroring, division, and merging again and again until the factors of two in the fractions approached five thousand. He was not satisfied either until the results neared the absolute regularity and impersonality of narrow stripes, combined with the unpredictability of their width and colors. Finally, in a process called Alu-Dibond, he turned them into digital prints on aluminum-based metal sheets, behind Perspex. While scale has a great deal to do with their success, so does the combination of translucent and reflective surfaces. Even in smaller works, the intense colors and ample white stripes can induce at least mild nausea.

A single other work at the gallery, a freestanding frame holding six parallel sheets of glass and first realized in 2002, pursues a related interest. It assaults Marcel Duchamp, the architectural ideal of the glass house, recently an inspiration in painting to Stefan Kürten, and the tradition of painting as a mirror or window. It illuminates why the stripes are more than another exercise in geometry from Kenneth Noland or Gene Davis. One does not have to choose between the meditative glow of oil painting or the metallic sheen of aluminum. Painting, appropriation, and technology may seem like contrary extremes. For Richter, they are as necessary, stable, rigid, and discomforting as the extremes of a three-legged school.

New media have let something loose in Richter even in his eighties. His gallery quotes Buchloh, who argues that he can thus reflect critically on dehumanizing and all-encompassing technology without pretending to a purer past, in nature or in art. Fair and insightful enough, but Richter was always showing how to reinvent himself by quoting a past one would just as soon forget, especially in postwar Germany. No one more embodies the postmodern paradox: make it new, not unlike Modernism, but by reflecting on Modernism as past. Call the results beauty or conceptual art, as you wish, but they will have you reeling, too.

Gerhard Richter officially ran at The Met Breuer through July 5, 2020, and at Marian Goodman through October 13, 2012. By the time of museum reopenings after Covid-19, though, it had already gone, although four "Birkenau" paintings have since gone on display at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 18, 2021. Related reviews examine the 2002 Richter retrospective and his series based on the Baader-Meinhof gang.