Smoke and Mirrors

John Haberin New York City

Roy Lichtenstein: Early Paintings

Brushstrokes and Chinese Landscapes

You probably know the story. Art today is all a rush to the top. Sure, Modernism shocked, but it had class—or at least upper-class white buyers. Now art takes its lumps from politicians, too, but happily. Young artists, you see, need shock tactics. How else can they go right for fame and find it? Irony rules, and the art world, that hoary institution, looks more settled, elegant, and downright trendy than ever.

Something remarkable happened this fall. The story came true without my complaining. Roy Lichtenstein took up his cartoons and pretend brushstrokes. Yet one would have missed plenty in seeing only pat answers.  Lichtenstein shows how much beside irony he puts in. As a postscript, I return to him late in life for his "Chinese Landscapes." Can it be entirely a coincidence that they go on display in the same space as dot paintings by Damien Hirst barely a week before?

Lichtenstein shows how much beside irony he puts in. As a postscript, I return to him late in life for his "Chinese Landscapes." Can it be entirely a coincidence that they go on display in the same space as dot paintings by Damien Hirst barely a week before?

Give and take

Of course, you should know the story. It comes as part of the sales pitch. It also allows backward-looking critics like me to complain how everything is going downhill, just as we look eagerly for the latest and trendiest successor.

The puzzle of categorizing years of art as modern or postmodern remains. Yet if one generation really fell between the cracks, I vote for Pop Art, with its gentle humor and identity crises. Two exhibitions only mystify the missing years that much further. Gagosian brings together some of Roy Lichtenstein's very first Pop compositions, from 1961 and 1962. Barely two blocks further uptown, Mitchell-Innes & Nash leaps ahead to later work based on brushstrokes.

Whereas Gerhard Richter and Richter's late work represent brushstrokes indirectly, Lichtenstein has done it with flair for almost forty years. In his first attempts, not on display, he simply introduces a brushstroke as an image, much as Edvard Munch had once used one reproducible medium, lithography, to represent another, a woodcut. Its bold, black outline cuts across his trademark open fields, Ben-Day dots, and industrial-strength colors. Already he relishes the drama of abstraction while reducing it to a cartoon, and already it functions both as technique and subject matter.

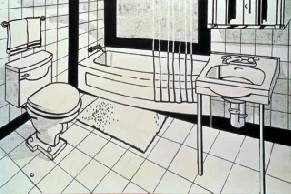

But then, art worked that way for Lichtenstein. Modern artists had already incorporated commercial paint and even automobile fenders and billboard ads, in part because it seemed the only appropriate way to represent objects in an increasingly manufactured world. When Lichtenstein takes on dots and outlines, well before Philip Guston took on Krazy Kat and abandoned abstraction, he extends the logic even while parodying it. An early Bathroom holds a disturbingly gritty edge alongside its deliberate artlessness.

One sees the give-and-take more obviously in composition books labeled Composition or pedantic diagrams of a Paul Cézanne portrait or Picasso women reduced to a textbook of their own. Yet it also goes into Lichtenstein's cartoon images as blown-up cartoons. One easily forgets that Ben-Day dots never dominate his work, especially in the early paintings. They stand as but one device among many, in a structural analysis of modern art that frankly admits to its own reductionism.

Modern art enters its dotage but keeps on painting. It sounds like de Kooning's encounter with Alzheimer's—or the visceral relation to oil and image—made literal.

Have fun!

Once the game gets going, there is nothing for it but to play harder. Compared to the famous Pop works of the later 1960s, the rough plainness of the first black-and-whites comes as a shock. So, too, do the new devices—and simple pleasures—that he throws into the mix.

Were cartoon brushstrokes not enough? Soon come somewhat smaller smears of loosely blended color. More personal and less satirical, they still blow up a brushstroke as if on a slide. More mind games come in three dimensions, with brushstrokes shaped into art-deco furniture and public sculpture. One out front of the Seagram Building right now mimes an Alexander Calder—and puts him to shame.

On canvas, brushstrokes start to cavort more far freely and densely than in the brushwork illusions of David Reed and James Nares. If Richter's sense of pleasure and control emerge only slowly as one looks, Lichtenstein has nothing to hide. But then these are only cartoons, right? Go head, they seem to say, for better or worse. Have fun!

Modernism always had two sides, its philosophical puzzles facing off against instinctive rewards. Bare refusals of art stood besides art that reveled in its spiritual and material pleasures. For rigor and indulgence alike, think of Joan Mitchell. More than perhaps any artist after Jasper Johns, however, Lichtenstein merges the two traditions. And unlike Jasper Johns, he has no interest in challenging the viewer. One may not know where to stand in front of a flag or target, but the black-and-white paintings and brushstrokes remain comfortably as art objects.

If Lichtenstein's later work gets weaker, it always aimed for entertainment—and for gallery walls. Mitchell-Innes & Nash cheats, though, when it claims four decades. One painting, a cheerful, colorful mess, dates to 1959, before the breakthrough years. From there, the show skips briefly to the 1970s before lingering on the more recent past. (One does have to sell art.) It leaves one with an old artist at best recycling his history. Hmmm. The similarity to Richter looks stronger all the time.

After the smoke of Abstract Expressionism comes the mirrors. If modern art still looks defiantly at the present, Lichtenstein comes off as an Old Master by turning on the past. Modernism and Postmodernism survive once more thanks to each other. Can they do it forever? Apparently, it takes some clever tricks and some posh uptown galleries. I guess I should linger on them while I can.

A postscript: "mechanical subtlety"

Roy Lichtenstein may have his brushstrokes, but someone else just will not give up on dot paintings. Eight years later and back at Gagosian, more than a month has passed, along with hundreds of paintings and untold thousand of colored circles by Damien Hirst. Now all are gone from eleven galleries on three continents. Yet dots remain in place, at least on 24th Street, by the man who can fairly boast he did not invent them, Lichtenstein. I wish I had thought of the juxtaposition in time—and he might well have, had he not died after finishing them in 1997. They make a fitting ending to a career begun in Pop Art but immersed increasingly in the history of art and design.

"The Chinese Landscapes" have all the ethereal precision in Chinese art that Hirst consciously rejected. So, however, did Lichtenstein, if one can take anyone him at his word. "I'm not seriously doing a kind of Zen-like salute to the beauty of nature. It's really supposed to look like a printed version." After all, he did introduce Ben-Day dots into painting, with images right out of comic books and printed matter. Not even Andy Warhol and Warhol's influence made appropriation so visible.

Still, the beauty is real, and if the landscapes are not, blame the Song Dynasty from before 1279. Hirst and Lichtenstein shared Gagosian once before, as part of "Ecstatic Abstraction" in 2009. Maybe neither ecstatic nor abstraction comes to mind when one thinks of either artist, but here they do. Overlapping hills come bathed in light, and they dissolve up close into dots and the space between them. Lichtenstein took his subject from fine art—twice over in fact, after seeing Edgar Degas and Degas prints at the Met in 1994. As a hybrid of Chinese screens and colored dots, the canvases partake of both painting and calligraphy.

Is he an answer to Hirst, then, or more of the same? Are Degas and China a double inspiration or two calculated removes—the mountains of Asia or mountains of stereotypes? Gagosian keeps one asking, and the dealer has kept returning to Lichtenstein in series since at least 2001, with his early work in black and white. And some days his entire career seems a falling-off in energy from the comics and the handmade. The "Entablatures," say, seem to me the worst of both historical pretension and glibness—but even the metal sculpture here, for rocky crags out of Asian landscapes, never lets its die-cut process stand in the way of routine. Still, his "Brushstrokes" carry their wit and punch, enough to compete with James Nares and Reed, and Lichtenstein exited perfectly by dissolving into mist and, in his words, "mechanical subtlety."

Of course, mechanical and subtle are not always at odds, or everything from Post-Impressionism on would be in big trouble. Even beyond Hirst, dots have seemed everywhere this year, as cryptic marks of personal identity. Kathy Goodell crafts them from ink on paper before pasting them into grids curving outward behind glass lenses. Just the month before, Richard Kalina had his share of dots, along with ovals and other layerings of tracing and cut paper. He finds ideas in molecular structures, but I thought more of stained glass and tinker toys. Jaq Chartier turns DNA testing into color charts.

If Lichtenstein was closest to Pop Art when he painted more obviously by hand, Joseph Masheck sees even Andy Warhol as depending on the handmade—only not his hand. Where Arthur C. Danto interpreted Warhol's Brillo boxes as indistinguishable from the original or from each other, Masheck argues, Warhol relied on the Factory precisely because it entailed a more "slapdash" means of production. If he is right, those plywood boxes, in all their silkscreened color, were a direct assault on the deliberately unsubtle geometry of Donald Judd. Not that Minimalism strictly precludes the luminous either, as with Dan Flavin. Its immersion of art and viewer in a shared space also undermines regularity, because the object enters an ever-changing theater. Lichtenstein's unique contribution may have been a return to the mechanical and the subtle.

Roy Lichtenstein's early black-and-white paintings ran through December 22, 2001, at Gagosian uptown and "The Chinese Landscapes" in Chelsea through April 7, 2012. His four decades of "Brushstrokes" ran through January 12, 2002, at Mitchell-Innes & Nash. Joseph Masheck's "Brillo, Warhol, Danto, Bidlo: Da Capo" is reprinted with light edits in Texts on (Texts on) Art (Brooklyn Rail/Black Square Editions, 2011).