Targeting Modern Art

John Haberin New York City

Well, a painting of a flag is at once a flag and a painting and there's no avoiding that.

—Jasper Johns (in conversation with Irving Sandler)

Jasper Johns: A Retrospective

Jasper Johns in retrospective is overwhelming. This museum blockbuster extends far more than a block. It crosses state lines.

The Whitney Museum gives it every nook and cranny of its largest floor, for more than two hundred works. An opening wall of prints, hung salon style, brings home how many of them have become central images of late modern art—and then the career survey starts all over again at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, on much the same scale. It is overwhelming for another reason, too: it sums up an artist's life, from youthful exuberance to anticipations of death. If you have lived through those years, it may sum up your first encounters with art as well. Nearly sixty years after his first target paintings, he is still targeting modern art.

How can all that be true? What can maps, flags, numbers, and targets conceivably say about Johns himself? What can they say about modern art or, for that matter, the United States? The show's title, "Mind Mirror," speaks to the inner world of an artist's mind and the outer world that art can hope to reflect. It speaks to the motif of doubling in some of his best-known works and the mind games that they play. Oh, and it speaks of the show's wild layout over two museums, comparable but never quite the same—and its overwhelming challenge for you.

These are flags and targets, but not where you expect them—up a flagpole or on a distant tree. They are literally in your face. Johns is not waving his white flag in surrender, and the boldness of Three Flags, one in front of the other, still pops right off the wall. It makes them all the plainer and all the more unfamiliar. Things are what they are and are not. With Johns, so is art.

Keeping to himself

With the death of Robert Rauschenberg in 2008, Jasper Johns rules unchallenged as greatest living artist. At least I cannot name a challenger, and I often wonder who that will leave after his death. For now, he keeps reflecting on his past and working out his future in sculpture, collage, and paint as he enters his nineties. Not everyone, though, is buying. You may think of great artists as the de facto leaders of a movement, like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning in Abstract Expressionism—Helen Frankenthaler and Joan Mitchell in color-field painting soon after. In movement after movement, Johns plays instead the great contrarian.

Born in 1930, he painted big and brushy like AbEx almost from the start. He adopted the blacks rich in color of Ad Reinhardt and the bright primaries of Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, and ever so many others. What, though, was he doing when he allowed images into art, years before Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, as recognizable as maps and flags? Was he mocking the heralded triumph of American art or wallowing in it? When he moved to New York in 1953, he seemed determined not to join the crowd, but to find his own. His beach house in South Carolina caught fire in 1966, as if he had personally destroyed his work to put the past behind him.

His turn in the 1950s to familiar images inspired the next big thing, Pop Art—but just what do they have in common other than an alternative to abstraction and academic realism alike? He has no interest in keeping up with fashion like Andy Warhol or the comics like Roy Lichtenstein. Neither, no doubt, did Rauschenberg, his friend and for a while his lover, whose combine paintings inspired Pop Art as well. Like him, Johns preferred the experimental scene to art's bar crowd or popular culture. Rauschenberg, though, was by nature a collaborator, as Johns was not. At the very center of a movement, he kept to himself and apart, like Michelangelo to Rauschenberg's Raphael.

The black of his abstractions and the stripes of his flags lead directly to the black paintings by Frank Stella. And Johns had his museum breakthrough at the Whitney in 1959, the very year that Stella appeared in a group show at the Museum of Modern Art. (The Jewish Museum, gave Johns a solo show in 1964, a reminder of how much it meant back then to contemporary art.) Still, he was not giving up on imagery any time soon—and then he did give it up for crosshatch painting, just as Minimalism was losing steam. Even then, though, he claimed an inspiration in a painting by Edward Munch, in the appearance of a passing car, and in dance. He named one in honor of Merce Cunningham, as Dancer in a Plane.

What had he given up, and why? He still turned to everyday life for casts of Savarin coffee cans, Ballantine beer, and a flashlight that look like appropriations but are not. It gave his art a still greater conceptual edge, just as artists were turning to conceptual art. One can is hollow and its mate is solid, but you would never know without lifting them both—which of course you never can. Still, he was again leading the way while standing apart. And then, against all odds, he began instead to look back.

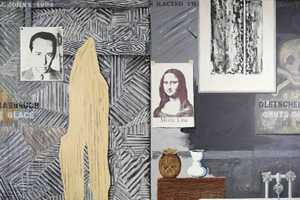

Nothing else has so infuriated his critics. Paintings within paintings quote his work and his life. Not that Johns himself appears, apart from the cast of a leg or a silhouette. With a warning sign for falling ice over bathtub faucets, in Racing Thoughts from 1984, one can picture him wallowing in hot water or his fears. A photo in the same painting of his dealer, Leo Castelli, looks downcast, too, and a print resembles an x-ray. That is a long time now to be obsessed with mortality.

Mirror, mirror

Mirror, mirror on the wall, what gives? If he has kept changing, it merely affirms his continued relevance—and if he refuses to change, his motifs still look fresh after nearly sixty years. He never quotes himself without adding something. In the last room at the Whitney, overlooking the Hudson River, Johns recasts portions of a number painting in four different metals. He is still living between two and three dimensions, still drawing on the impact of monochrome, still a colorist, and still thinking aloud. For all that he learned from another close friend, John Cage, he leaves nothing to chance.

He was a gestural painter from the start, and every crosshatch is a gesture. The largest maps are just plain exuberant. Paint cans hang down over a canvas to represent Johns in his studio while another panel juts out the bottom, because not even painting can contain his art. Something ominous was present from the start as well. An early target print looks like a human eye, and four plaster faces without eyes loom over some of the first targets as well, with intriguing echoes in Philly in a show of Emma Amos a floor below. It is not a long way after all to his skulls.

The curators, Carlos Basualdo of the Philadelphia Museum and the Whitney's Scott Rothkopf, are not alone in attributing a darkened mood to his breakup with Rauschenberg in 1961. He paints Disappearance in black and Good Time Charley in gray, an allusion to his lover's sociability and the fading of love. A ruler descends, swiveling on a point, to knock over a drink. Still, it is not so easy to date work to before or after the break-up. In Memory of My Feelings sounds autobiographical but quotes Frank O'Hara, the poet, and Diver refers to the suicide of Hart Crane. As the saying goes, all of life is slow dying.

This is his life all the same—and not just in later work. Johns must himself have favored that cheap coffee and beer. (Try to imagine Andy Warhol doing housework with the contents of Brillo boxes, although he did, he liked to say, make a lunch from Campbell's soup every day.) Nor was mortality outside the mainstream even then. Warhol, too, kept returning to images of death, like the electric chair or a skull in the Jack Shear drawing collection. If Johns is guilty of self-pity, so is Philip Guston, equally in your face and equally behind a mask.

This is his life all the same—and not just in later work. Johns must himself have favored that cheap coffee and beer. (Try to imagine Andy Warhol doing housework with the contents of Brillo boxes, although he did, he liked to say, make a lunch from Campbell's soup every day.) Nor was mortality outside the mainstream even then. Warhol, too, kept returning to images of death, like the electric chair or a skull in the Jack Shear drawing collection. If Johns is guilty of self-pity, so is Philip Guston, equally in your face and equally behind a mask.

That persistence marks his place apart, apart from abstraction or realism. "Mind Mirror" alludes to art's old claims to imagine and to mirror nature. And he did say that he adopted "things that the mind already knows." The impulse to paint a flag came to him in a dream. A flag print, Moratorium, came in support of the 1969 moratorium to end the war in Vietnam, a demonstration and teach-in—when nationalism took on a bitter edge. Still, realism is something else again.

I have a pet peeve about crossword puzzles in The New York Times. They keep cluing eta, the Greek letter, as "resembling" H. It does not, no more than the first letter in art resembles A. It simply is H. In the same way, Johns is not representing things but making them. Not that he was above illusion, like the painted bronze or the shaded edges of a painting within a painting. Yet the numbers really are numbers—or are they?

Lying in plain sight

Can you see things for what they are? That could be art's most pressing question, and Johns never stops asking. To a degree, it is up to you. I have a poster of a Johns map, and I check it all the time for help with geography. You can, should you see fit, salute his flags or shoot at his targets, if at a cost. And that cost is part of the work's logic as well.

The logic of the literal extends to another persistent motif, art of its own making. The string in a Johns Catenary takes its shape under nothing more than gravity—in one case (wordplay alert), next to a painted photograph of the Big Dipper. When a ruler or a broom sweeps across the canvas, who needs a painter? Yet these could also be gestures of effacement. Jacques Derrida spoke of texts as sous rature, or "under erasure," and Johns might well agree. The mark of a censor extends to shades of gray.

Does his significance lie in the literalism or the subtlety? Philosophers like Rosalind E. Krauss and Arthur C. Danto argued for the art of his time as indistinguishable from what it copied. Krauss trumpeted an end to the "originality of the avant-garde," Danto the beginning of understanding. Others, like Nelson Goodman, saw instead an invitation to look harder, where every difference counts. As I have written before, they could stand for dueling impulses in modern art, from Dada to abstraction—to know and to see. And no one has combined those impulses more than Jasper Johns.

It still keeps him apart, even as he keeps up with his times. He has a particular liking for Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp. He uses early and late paintings by Picasso as motifs, while the silhouette of Duchamp appears in According to What, along with color names spelled out in 3D and in all the wrong colors. Both were leaders of a movement, Cubism and Dada, who became soloists without an orchestra. Johns, too, has his differences. They make him inescapable but ever so hard to know.

The mirroring of two museums comes with its differences as well. Both proceed more or less chronologically, but with rooms that focus on a single motif—the Whitney with flags and maps, Philadelphia with numbers and skeletons added only recently to his own silhouette, in that growing consciousness of impending death. Each also has a focus room on a single painting, Philly with Untitled from 1972, gliding from crosshatching to cast body parts of unnamed friends, so that the patches between them become suggestive of human skin. The Whitney settles instead on According to What, that virtual compendium of his literalism and deception from 1964. Each, too, recreates an entire exhibition at Castelli. Both museums claim a special relation with the artist, although the Met contributes White Flag, MoMA the most iconic flag and the largest and most thrilling map.

In both museums, things are what they are and are not, including the face of the artist. Johns could be the most reticent of painters, even as he inhabits so much of his work. He could be the most truthful as well, while lying every step of the way. Is he no more than Guston, with all the self-pity but without the Ku Klux Klan hood? He is not so much wallowing as sticking to his guns. For nearly sixty years, he has been lying in plain sight.

Jasper Johns ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art and the Philadelphia Museum of Art through February 13, 2022. Related reviews look at Johns in gray, his "Catenary" paintings, "Three Flags," and "Regrets."