Confession and Spectacle

John Haberin New York City

Gallery-Going: Soho in Spring 1999

Tracey Emin spews out her feelings. Chance sketches and loaded phrases, obscene graffiti on torn notebook sheets—they cover the gallery walls with what seem unmistakably an immediate record. A voice on video plays against grainy pans across seedy city streets, the turf of fearful side alleys and repulsive personal histories. And of course the voice is her own.

What does it meant to document oneself when one expects art? Is it obsessive, a harsh, compulsive recording of time and impulse? Or is it on the contrary a casual disregard for making art the old-fashioned way? Emin forces one to ask.

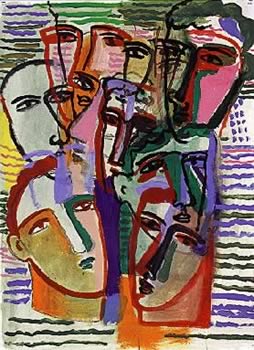

I wanted to ask anyway down in Soho, where Neo-Expressionism ruled supreme. Julian Schnabel, as well as Sandro Chia and Philip Taaffe, was on display, bringing back the tumult of the 1980s. Emin, a British star of the moment, brings one back to the puzzle of the prefixes—neo and post, and all the conflicts they demand. They make a pretty good excuse to hit Soho, before Memorial Day brings another gallery spring formally to an end.

Confession and cliché

Secret narrative or direct personal confession? Eternal repetition or blatant refusal of the past? Oddly enough, they all sound just like art. Art concerns each of them, in one cliché or another.

Iconography finds hidden symbols in religious painting, like the postmodern fascination with art as text. Art as self-expression holds all the creator's psychic conflicts. The canon, which no good conservative should be without, locks every artist into a relationship with tradition. The avant-garde tosses it all away with gusto.

Postmodernism is supposed to thrive on cliché, undermining Modernism's elitist vision of fine art. It is also supposed to critique them to death. So one should not be surprised to see the elements all hanging when Emin goes to work. Postmodernism does not resolve Modernism: it just keeps banging into it head first. It insists that the theater of self-expression is always in part a stage set. Jean Baudrillard, the French critic, calls it spectacle.

Emin certainly likes text. Her writing, hard enough to read on paper pinned to the wall, sometimes expands into neon light tubes. Horrible spelling only adds to the puzzle of care for the self or disregard for art.

The narratives speak of early, constant sexual activity, wavering between pleasure and relief, victimization and fear. Occasionally I found the headlines pretty funny. More often, they feel explosively angry, sad or threatened, or just too obscene for a family medium like this one. Her favorite image is her splayed crotch, going right back to Egon Schiele.

At first the trivial tone, personal focus, and politicization of sex all made me want to walk off. I longed for the maturity with which Maria Epes can handle feminism and violence. I stayed only for the funny lines. Before long, though, it dawned on me that the immediacy has little in common with Robert Longo and his daily memorabilia or Hanne Darboven and her meticulous, formalist calendars. For one thing, much of it addresses the same actor, Emin herself—and a quite distant past. For another, the air of theater goes beyond life's sordid melodrama. Emin emphasizes not her naked flesh, like John Coplans, but the props.

Children's theater

The collision between confession and theater comes more naturally to Sophie Calle, as well as with a finer and more vulnerable comedy. Still that collision gives Emin's show the bitter edge she does not always have. It does not so much raise the scraps of her work to fine art as make her very life an ongoing theater—oh, that postmodern spectacle. Paradoxically, it makes the viewer's life part of the spectacle as well. Has the art scene become all about sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll?

A tiny portable TV shows her (as ever) face and genitals forward, talking about her sex life. It rests on a low, raised platform, facing two small chairs, the kind from a child's furniture set. Is she talking about her past or addressing it from a distance of years? Neo and post are at it again, with exactly the puzzle that makes the best contemporary art so haunting.

Beyond the child's furniture, in a back room, a rumpled bed enacts the scene of illicit sex. Money lies among the crushed props on the floor. Of course, Emin could not really conduct her sex life in the gallery office, at least I think not. (Some recent video art has me guessing.) If I had any doubts that a British woman had staged a drama for a New Yorker like me, on the floor she dropped American money—and cheap stuff, too, ones.

Outside the videos, in fact, Emin chooses props so American that I could have entered a Whitney Biennial or two. (Talk of postwar art as the "American century"!) I could well mistake the wooden shed for the Spinning Room by Paul McCarthy. And no question, the postmodern spectacle has its drawbacks. It is only fair to report that I can attach no particular meaning to McCarthy's shed either. Sometimes a theater of anger and pain needs more clarity and fewer props.

I could not imagine Emin's urban England from these generalized images of anger and pain. As with McCarthy, I mostly shrugged off her history. Along with others influenced by graffiti's first wave such as Barry McGee and SWOON, I wanted the sadness of the real streets. I wanted her to get a life. And my reaction is not necessarily a good thing for issues of emotional depth and feminist outcry.

Not coincidentally, her postmodern forebears, such as Schnabel and Chia, have always had to struggle for respect. They suffer the charge of shallowness, while they work with serious issues on a scale not even Jackson Pollock might recognize. Like Emin, they themselves are the spectacle.

Sincerity and stardom

My visit to Soho felt like a step through a time warp. Schnabel had brought together his famous plate paintings. (I want to say "assembled," but, no, the plates still lie broken.) Elsewhere, Chia showed his latest. I could almost call it all Neo-Neo-Expressionism. Talk about the art world's spectacle.

Postmodernism typically stands for irony, political awareness, or cynicism. It means the heritage of Cindy Sherman and her Untitled Film Stills, even when Sherman addresses something as frank and disturbing as eroticism in Robert Mapplethorpe. How strange, to remember the very first postmodern spectacles. The events that shattered the old consensus pretended to almost pathetic sincerity.

Schnabel actually took up his dishware in 1978, but it got big publicity only after Georg Baselitz, Chia, and others had brought their Neo-Expressionism from abroad. The simultaneous work of two continents hit Modernism doubly hard. It suggested a new consensus, foreign to the quiet care of abstraction and Minimalism—and one no longer centered in America.

I consider Schnabel more than just shallow and cynical. For one thing, he took modernist painting seriously indeed, right from the start.

The broken plates make a painter's gesture into a tangible object, perhaps even more than his later ventures into sculpture. Think of formalism, which demands that one appreciate paint's physical support for what it is. Even when covered with oil, Schnabel's plates also project forward, a second echo of Modernism. Think of the Cubist planes, which jut out of the picture. Picasso's clever illusions and collage both overlay the traditional space of still life. For a third modern memory, Schnabel's wall-size canvases and broken skein of color allude to Pollock and "all-over painting."

Yet each of these devices does something it never would for Stella or Picasso, a big part of the spectacle: it shouts him. Pollock's own legendary image, captured on film and cultivated in Life magazine, nonetheless fell upon the shy, insecure, alcoholic painter as a fatal intrusion. It literally drove him to drink. The night after his last photo shoot, he went on a deadly binge. By contrast, Schnabel has no problem moving between stardom and a serious career.

Horny artists

Pollock loaded his work with his dreams and fears. The veiled male stick figures and maternal metaphors never disappear: they just learn their place. In the mature, magnificent abstractions, paint takes over the joint. The artist's gesture becomes paint's own dance.

By contrast, one knows nothing of Schnabel's special anxieties, but he never lets go. All one can gather from his work is that he cares about himself. A broken plate comes not from some unconscious, but from the five and dime. And yet the very anonymity of its history compared to a paint tube or Cubist newsprint allows it to take its associations entirely from the artist.

In the same way, the force of a shard's intrusion forward becomes Schnabel's demands for himself. If the abusively macho stance were not clear enough, one gets to stare down antlers. He sticks these props right out at the viewer, as obsessively male as Baselitz's drinking sessions. By comparison, Pollock's dance with paint seems delightfully effeminate.

There is a method to this profligate madness. Schnabel holds up the greatness of modern painting and watches it shatter on him. It falls apart like the plates. No expressionism, he says, Abstract or otherwise, can encompass his feelings.

Schnabel compliments himself shamelessly—in fact, twice over. The artist stands as the gold standard: his art defines paint's limits, and his ego exceeds his own art. The sentimentality extends to the obnoxious male posturing. He even gets to hedge, making a grand artistic success out of pretended failure. As with Emin's self-abusive record of male abuse, I find all this more than a little revolting.

Nostalgia and competition

Postmodernism always has a sentimental side, and it comes with the prefix, the post. There is a word for looking back and seeing oneself unable to recapture the past's greatness. It is nostalgia, another word in Jean Baudrillard's lexicon.

Emin's stage sets never let go of a nostalgia for childhood, any more than Schnabel can live without nostalgia for art's grandeur. Neo-Expressionism has not influenced critics nearly as much as postmodern irony, but it lingers through that neo, in such artists as Katherine Bernhardt with her consumption habits. The shows from Schnabel or Chia add a special irony, for recalling Postmodernism's origins takes some nostalgia of its own.

Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente, and Philip Taaffe thrive on nostalgia. No wonder they have become more sincere over the years, more comfortable with their art. Ironically, for the same reason I can no longer take them all that seriously. As with Emin, I want to feel the bite, and I do not. I actually miss cynicism.

Chia began with fat, pink, strutting figures. His oversized revisions of early Modernism depended on looking big and meaningless. Over two decades since then, he has kept the pudgy males, but he now aspires to something he considers truly serious, narrative painting. It sounds a lot like Fernand Léger's career, and it gets just as boring.

In the new paintings, people sit in cute little forest scenes or self-important public groups. Chia always made the main figure an emblem of the artist as poet. (I have reproduced a painting from last year's show as much for its gorgeous title, The Enigma of Flight as for the work.) Now the poems are narrative idylls. To ensure that one appreciates the forest properly, paint mimics Cézanne's blue-green patches. I doubt that anyone will stay with the thick, cracked swatches of cloying color long enough to follow the story. I sure did not.

Taaffe came from yet another neo, Neo-Geo. His early pattern painting treated abstraction with heavy irony. He still makes linen or canvas look like velvet, but he enjoys art more now, and his patterns have loosened up. He simultaneously competes with abstract painters and Andy Warhol with his irony, a huge mistake. Recent shows of the late Rorschach and urine paintings, not to forget Schnabel's own fine movie about him, proved that Warhol never gave up on the dark side of his art. Taaffe is taking a competitive risk, and it backfires big time.

I confess

Confession and spectacle—they explain why Emin and Schnabel, for all their failures, have me so intrigued. Ostensibly as opposite as the Brit pack's ironic manipulation and overblown human expression, they push the same buttons and probe the same dilemmas. Yet they also explain why I can never fully give up my own nostalgia.

There I was with my own obsession, returning to Soho on a broken leg. I imagined my doctor scolding me for all the stairs. I saw everything from busy abstractions by Tony Berlant to Nancy Rubins and her mammoth, mangled overhead construction. It looked like an airplane formed of crushed airplane parts. Compared to John Chamberlin's crushed automobile parts, call it a take-off in more ways than one.

For one last layer of irony and nostalgia, Chia's first New York gallery was showing calm, meandering abstract art. Guillermo Kuitca, an Argentine painter, starts with elements of architectural plans, then lets his imagination go.

I confess: the abstract paintings made my afternoon. But then again, my nostalgia for the good old days of modern painting is another part of the art-world spectacle. It mean only that I as a critic, like Schnabel as artist, wants to be taken seriously. Maybe I should spread my crotch.

Tracey Emin showed at Lehmann Maupin, Julian Schnabel at PaceWildenstein, Sandro Chia at Shafrazi, Philip Taaffe at Gagosian, Tony Berlant at Lennon, Weinberg, Nancy Rubins at Kasmin, and Guillermo Kuitca at Sperone Westwater, all in May and June of 1999.