Are You Satisfied?

John Haberin New York City

Jennifer Packer and Adam Pendleton

Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturism Period Room

Jennifer Packer calls her show "The Eye Is Not Satisfied with Seeing," but do not let that fool you. She is just plain not satisfied. How could she be, as a black woman in America? At the Whitney Museum, she asks to leave you restless as well. So does Adam Pendleton at the Museum of Modern Art, and so does an entire period room at the Met.

Finally, Richmond has knocked Robert E. Lee off his pedestal. His twelve-ton statue came down from its monumental position on Monument Avenue, to a cheering crowd. It was the Wednesday after Labor Day,  a time of new beginnings and getting down to business, not least in art. The Proud Boys are still proud, but the rest of us could, for once, have felt a little pride as well. And then just three days later it was back but this time in MoMA's atrium, thanks to Pendleton. Yet he, too, could take pride in cutting Confederate myths down to size, with Who Is Queen?

a time of new beginnings and getting down to business, not least in art. The Proud Boys are still proud, but the rest of us could, for once, have felt a little pride as well. And then just three days later it was back but this time in MoMA's atrium, thanks to Pendleton. Yet he, too, could take pride in cutting Confederate myths down to size, with Who Is Queen?

Space Is the Place. It is for white males with too much money and no clue how to spend it, but it was nearly fifty years ago for a keyboard player and composer with a still more ambitious vision. Their film of that name and its soundtrack album took Sun Ra and his Arkestra to another planet, which they proposed to settle with young African Americans—and their sole means of transport was music. That and a willingness to push the envelope and a healthy sense of humor. For the Met now, the means instead is art. It opened its Afrofuturism period room as "Before Yesterday We Could Fly," without a hint of free jazz.

Not waiting for an answer

Jennifer Packer painted a policeman for the 2019 Whitney Biennial, demanding in himself. Now back at Whitney, she opens with her largest single canvas, of a black victim of the police. Blessed Are Those Who Mourn honors both the mourners and Breonna Taylor, whose killers still go free. A subtitle all but screams her name, Breonna! Breonna! Packer is not the only one to have known, as a near abstract painting has it, Cumulative Losses. At its center, a blue could belong to a squad car's glass or to Mark Rothko.

Her subjects are not satisfied either—far from the African American icons of Amy Sherald, Mickalene Thomas, and Kehinde Wiley, and wall labels solicit comments from a fine painter of others herself, Jordan Casteel. Most are friends, at ease in her company, but at ease only to show their restlessness. It appears in a woman, uncertain whether to engage the artist or to look away. It appears in a man's posture, as The Body Has Memory. They might not be any more comfortable day in, day out. The next largest canvas, a domestic interior, is A Lesson in Longing.

The title quotes Ecclesiastes, the verse right before "there is nothing new under the sun," and she paints what she knows all too well. That means people and flowers, and she does not necessarily distinguish them. The people, like Taylor herself, hardly exist apart from home, the sole exception a pool hall, and Parker calls a flower painting Say Her Name. Another still life speaks of Absence, a Condition, but that policeman still has a very human presence. He is even, dare I say, enjoying himself. He is not waiting around for an answer.

These are not comforting portraits or interiors. A man hangs upside down, a reference to Marsyas, flayed alive by a Greek God. A nude crosses his hands behind his head as if under arrest, as Transfiguration but also, in its subtitle, He's No Saint. Clearly they have been around, and things are not changing any time soon. Taylor's bedroom is not the only one to include box fans, and a portrait includes a plain old typewriter. No one bothers to dress up, but the flowers sparkle with paint.

Parker paints what she knows, too, in the sparkle of paint, but that leaves gaps in what she sees. Drips run freely, less as drawing as for Jackson Pollock than as surrender to a messy reality, leaving blank areas. The yellow covering the nude's crotch could be a gap in what she knows as well. It is a modest show at that, of barely thirty oils and a very few drawings in pastel and charcoal, but then she is not yet forty. One wall hangs bunched up, salon style, so she is still not satisfied with what she sees.

Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta, who also curated that biennial, stick to just the last ten years. They note a shift to monochrome in the last five years alone, but accents of further color still bring seeing alive. In the single largest painting, from 2012, windows or spare paintings within a painting add cryptic presences. The diptych could represent an interior or a fire escape, with a woman visible and a man insistent. The title, The Fire Next Time, places it within the urban landscape of James Baldwin, but you may call it Parker's and yours as well. I hesitate to call this so much as a midcareer retrospective, but there is more than enough for now to be seen.

Off its pedestal

Adam Pendleton towers over my candidate for art's least manageable space. The atrium has defeated way too many artists and taken up way too much room in the museum since MoMA's 2004 expansion, and its 2019 expansion by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (in collaboration with Gensler) can do only so much to give it a function. It was at its best in 2021, in fact, when Amanda Williams pretended that it was no more than storage for museum furniture. So why not turn it into a theater? Pendleton's main screen faces the viewer coming in, and for once an installation seems to fit. It lacks only tiered seating.

It comes close, though, for the artist is just getting going, even apart from his standout role in the 2022 Whitney Biennial. As at the movies, the video comes with a soundtrack on speakers well apart from the screen. The entire installation becomes sound art, although deciphering the words takes doing. He also takes full measure of the atrium, with a black construction on all three walls, a full five stories tall. He might be rubbing in just how much space has gone to waste, but he sure makes use of it. One can imagine its tiers as tenements and fire escapes, for residents to hang out on a summer night to catch the show.

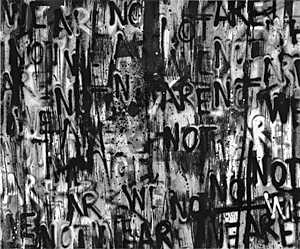

The Lost Cause has lost once again, only this time to black America and a vibrant urban culture. In fact, it already had by the time the statue came down, leaving a hallmark of public sculpture for Jessica Kairé, the pedestal. The video shows it smeared with spray paint, as it was in life. The black wall units serve as a handy place for smaller screens as well, with more words somewhere between street art and text art for Glenn Ligon,  in black and white. Pendleton, who appeared as an emerging artist in a New Museum "generational" in 2005 and Greater New York at MoMA PS1 in 2010, already brought word paintings to the Studio Museum in Harlem as an artist in residence in 2005. He treated graffiti as a weapon once more in "Grief and Grievance" at the New Museum just last spring.

in black and white. Pendleton, who appeared as an emerging artist in a New Museum "generational" in 2005 and Greater New York at MoMA PS1 in 2010, already brought word paintings to the Studio Museum in Harlem as an artist in residence in 2005. He treated graffiti as a weapon once more in "Grief and Grievance" at the New Museum just last spring.

Just what, though, is he saying? The audio combines poetry and protest by Amiri Baraka with crowd noise from Black Lives Matter. Other allusions are less clear, and they keep coming, with footage from civil-rights protests to turbulent natural processes. That makes sense for an artist who contributed to a show about Walter Benjamin—the Marxist critic who intended his "Arcades Project" as a stroll through the entirety of modern life. It can be frustrating all the same. Just who are they all, and whatever does this have to do with Glenn Gould?

What, for that matter, does it have to do with gay identity and queens? One large screen refuses to say, forcefully, with the repeated word NOT. Still, Pendleton is an optimist—the same artist who rendered the Congolese independence movement as a dance for a show of black performance art. The construction alludes to Resurrection City in protest on the Washington Mall in 1968, although it looks at home in New York. And the power of denial is just what took the statue down. It has finally tamed the atrium as well.

It still leaves plenty to the imagination, starting with the question mark in its title. One can picture to oneself the five-story street scene and its vitality, only to remember the inequality it bears. One can picture Resurrection City and the hopes of a movement, only to recognize how long it took to topple a statue and how much that leaves undone. One can hear the voices of Black Lives Matter, only to wonder when they will become clearer and whether anyone will hear. One need not trust to Pendleton alone to sort it all out. That still leaves the countervailing NO.

Space Is the Place

Yesterday does not sound all that long ago, although Sun Ra died in 1993. At this rate, I am going to designate my dorm from back in the day a period room. Right off at the Met, you may feel nostalgic for what you may or may not remember. A big, box-like TV drones on just as it might have before yesterday, rabbit ears intact. Almost above it, Ini Archibong suspends equally preposterous tubes as his Venus Chandelier. Yet the face on television is Jenn Nkiru, from Nigeria via Detroit's techno scene, and Archibong, son of Nigerian immigrants, is under forty. Just what period is this?

You may be asking before you get there, to a spot between medieval art and the Met's American wing—and just off British galleries from an age of imperialism and luxury. Sun Ra had his intergalactic conversion experience as early as the 1950s, but Afrofuturism is having a revival, with such adherents as Beyoncé. Roberto Lugo includes her among his colorful "portrait cups" along with such African American artists as Horace Pippin and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Zizipho Poswa draws on early American and South African ceramics as well. With them and others, the room accommodates two continents and at least two traditions, while messing up the distinctions. It just does not have much to do with Afrofuturism.

Part of the period room pays tribute to Seneca Village, with a recreation of hearth and home, even as the Brooklyn Museum rehangs its American wing with a map of the Lenape nation out front and greater weight to Native American art—before, a year later, changing its mind. A community of Irish immigrants and, predominantly, free African Americans, it stood west of the present-day museum, only to give way to Central Park—a process that MoMA PS1 sees at work in the bulldozing of community gardens today. (The Met has been taking revenge with its nasty expansions into the park ever since.) To the curators, Hannah Beachler and Michelle Commander, "We walk on hallowed ground." Wall text also takes due note of displaced Native Americans, the Lenape people, and Corlear's Hook, a black neighborhood closer to today's financial district or Lower East Side. Art in New York is doomed to navigate between gentrification and reclamation.

The other side of the story starts an ocean away—and between art and design. Yinka Ilori from Nigeria, the country of Onyeka Igwe, assembles six chairs as Swimming Pool of Dreams, while Jomo Tariku builds on chairs from Kenya. Cyrus Kabiru has his Kenyan eyewear and Fabiola Jean-Louis a corset dress from Haiti. In this context, it could be liberating or confining. So indeed could the room. It has only a narrow space to circulate around those two components, with more art on the facing walls.

That means a space in New York, where the cross-fertilization takes place, for all the lost opportunities. Any period room shows off the permanent collection, but the Met acquired some work in building this one and commissioned others. Much of the decor goes to Njideka Akunyili Crosby from Nigeria, for wallpaper that approaches abstraction for all its hints of other landscapes and histories. Willie Cole created his African totem from black high heels as long ago as 2007. Tourmaline, better known as a writer and activist than an artist, inserts her queer trans totemic self into saturated color photographs. They may not be Afrofuturist, but they do hold out hope for the future.

Highlights may come down to Western art after all, sophisticated but African American. It, too, commemorates the past from the perspective of the present. Whitfield Lovell brings a precise charcoal portrait of a figure from early in the last century, while Henry Taylor finds a hero in an African American woman. Andrea Y. Motley Crabtree, a pilot in the military, sits at ease with her helmet on her lap. The tall acrylic has the casual fidelity of Alice Neel, but with greater impasto. Before yesterday, she could fly.

Jennifer Packer ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art, through April 17, 2022, Adam Pendleton at The Museum of Modern Art through January 30. The Afrofuturism room at The Metropolitan Museum of Art opened November 5, 2021.