A Visible Blackness

John Haberin New York City

Shaun Leonardo, Wardell Milan, and Kenny Dunkan

Just when white America thought it could ignore "those people," the Bronx Museum makes clear that it cannot, with Shaun Leonardo and Wardell Milan. With his drawings this spring, Leonardo bears witness that black lives matter. He could just as well, though, be witness to a haunting. Now, too, the Bronx takes a long look at contemporary art by women, where women of color have pride of place. Evening performances display in turn The Black Male Body, The Female Body, The Trans Body, The Migrant Body, and The Quarantine Body. So much naked flesh should cover it all.

Right on the way in, Wardell allows black males to strut their stuff in collage, with boxing as their Battle Royale. How, then, can he follow them up with the epitome of the angry white male? If blacks are invisible to Donald Trump's America, that could be point. Meanwhile in down Tribeca, Kenny Dunkan dances in public and constructs a sculpture from nuts. No, not nut cases, although his art might seem dedicated to them, and he carries on more than a bit himself.  Even at his tackiest, though, and in hardware, he just wants you to recognize what you might prefer to ignore.

Even at his tackiest, though, and in hardware, he just wants you to recognize what you might prefer to ignore.

Witness to a haunting

Just whose breath fills "The Breath of Empty Space" at the Bronx Museum? It might be the breath of a young black man, facing forward, as if to insist that he is still there. It might be lost in the darkness of a road at night or hovering like a ghost in the headlights. It might have been visible once, had Shaun Leonardo not cut away large swatches from other sheets of paper. It might be your own breath, for he has replaced some of those swatches with mirrors. The mirrors can multiply images or make them that much more confining, for there may not be nearly enough breadth in the breath of empty space.

Blacks, he seems to say, feel haunted all the time. They have seen the ghostly presence of headlights, from police cars in the rear-view mirror. Police had stopped Philando Castile, for one, more than fifty times before another pointless encounter ended in his death. They may by now feel like ghosts themselves or on the point of death. Leonardo nurtures that experience in charcoal, which can take on the sharpness of photorealism or the blur of many a photo. It can capture the shadows or the glare, just as Alfredo Jaar captures the sensation of tear gas in video at the 2022 Whitney Museum.

Even in the museum's smaller gallery, he piles on those devices, but with the consistent silvery contrasts of charcoal, mirrors, and ghosts. He immerses precise portraiture in indefinite spaces. He adopts the "decisive moment" of photojournalism to keep up with the news of African Americans at risk, and the unreality of a photogram. He may need them both, just as Sigmund Freud found entirely banal images at the heart of "the uncanny." He explains no more than he has to explain, in the work's titles. Who at this point can remember one killing from another anyway?

If Leonardo piles it on, he may feel the need to do so, to avoid giving in to sentiment. When it comes to premature deaths or police violence, people know what they know. Mine is surely a sentimental review. Then, too, he has to rely on the photographs of others—from the families of the dead, from social media, from mug shots, or from the media, conventions and clichés intact. In response, he can fall back on skill or turn the focus, with cuts and mirrors, to the museum and to you. He may pile it on to keep up with the sheer number of the dead as well.

With its name alone, Black Lives Matter demands that one think in the plural, and that is never easy. As with #MeToo, it invites one to feel empathy and solidarity, but numbers can be numbing enough to stand in the way of action. I confess that I had to check that Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd in Minneapolis, rather than yet another victim of police violence somewhere else. That, you may think, is just what political art can contribute, a dedication to particulars, like the sensation of tear gas in video by Alfredo Jaar at the 2022 Whitney Museum, but I am not so sure. Art is not by its very nature about individuals and personal expression—or, conversely, about universals like religion, structure, and form. Rather, how artists deal with the choice defines periods, movements, and the artists themselves.

Leonardo does pile it on, and you may have your doubts. He also has to decide where his subject begins and ends, and that is not easy either. He includes not just the dead, but also the Central Park Five, unjustly convicted of assaulting a white woman jogger in 1989 and in prison for up to thirteen years. He includes as well not just individual encounters and outright innocence, but also the Attica prison uprising of 1971. Hostage taking and tense negotiations ended in more than forty deaths, ten of them of police and staff. His charcoal is no less sharp for that—and the mirror no less on you.

Terrorists in terror

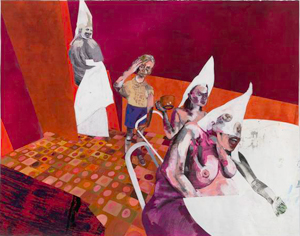

In truth, there is more than enough grief and grievance to go around. That survey of women, "Born in Flames," has its share of body parts, dismembered or in pain. The performances are Five Indices on a Tortured Body, a play in five acts. Zachary Tye Richardson, the dancer and choreographer, takes on the harsh colors of stage lighting by Billy Ray Morgan. The stage set looks grim as well, broken only by bars. And Wardell Milan introduces it as "Amerika," with images of the Ku Klux Klan.

Milan harkens back to protests in the 1960s—when German was the language of Nazis rather than a social democracy from which America with a c could learn something. A subtitle, "God Bless You If It's Good to You," is at best resigned. The Klan seems newly relevant at that. And Milan began with a question that situates the action firmly in the present, after a January assault on the Capitol "What," he asks, "do terrorists do when they're not terrorizing?" Whatever it is, you may wish to answer, they are up to no good.

Milan harkens back to protests in the 1960s—when German was the language of Nazis rather than a social democracy from which America with a c could learn something. A subtitle, "God Bless You If It's Good to You," is at best resigned. The Klan seems newly relevant at that. And Milan began with a question that situates the action firmly in the present, after a January assault on the Capitol "What," he asks, "do terrorists do when they're not terrorizing?" Whatever it is, you may wish to answer, they are up to no good.

The curator for both current shows could only agree. For Jasmine Wahi, Milan lays out "the violent undergirding of contemporary American society," and violence here is the disorder of the day. A cross dominates his largest painting, set against an acid red that all but swallows the bare landscape and the Klan alive. Reclining nudes out of Edouard Manet have their extremities cut off. A man holds one hand to the side of his head in puzzlement or fear. A woman thrusts out her breasts, in self-assertion or in agony, while caught in a scream.

Those tormented faces, though, might not be so quick to agree. What are they really doing? The answer, it turns out, is not much at all, for they are terrorized themselves. Those figures in a landscape are just standing around, and the most active among them are women. They are not even all that white. Anti-Negress may from the sound of it insist on whiteness, but it depicts blacks, and the title could just as well refuse a demeaning label, the N-word.

Milan's charcoal, graphite, pastel, china marker, and oil slick encompass the coarse and the smooth. Brushwork straight out of Francis Bacon disfigures faces and flesh. Etchings add excruciating detail, as The Balcony. In a play of that name by Jean Genet, men bring their loathsome fantasies to a brothel in the midst of a revolution. Nearby, Morgan translates the echoes of Bacon into plaster. He leaves exposed its literal undergirding in polyurethane and plastic, like a deep physical wound.

The press has its own clichés about a reactionary's downtime. Surely all Americans are just people, with loving families and personal stories, if only liberals would listen. Milan gives every Klansman and female warrior a face and a name, but not just in sympathy for the devil. He may muddy racial identity, but in order to clarify a country torn apart by race. His collage boxers appeared back in 2007 at the Studio Museum in Harlem, as warriors but also dancers and dreamers. He has his shortcuts and his stereotypes, but he is still dancing and dreaming.

Twin towers

Tourists had no idea what they were missing. People out for the Eiffel Tower on a sunny day shared the Champs de Mars with Kenny Dunkan, who was creating his own work of art, from himself. His back to the tower, he kept up an improvised dance, while others turned their back on him. He is still dancing at that, on video, in a show all about the body—his body, as a person of color, and what others choose to ignore. If the tower has pride of place even now, its slim curves almost framing his, all the better for a French artist from Guadeloupe with a hip-hop tone to his work's titles. As the show's title has it, "Affinities Are Miracles."

Do not be too quick to blame the tourists. Dunkan's shuffle, on the face of it, is nothing special, and I, for one, am used to ignoring street performers as at best a nuisance in New York. Besides, they had come a long way to see Paris, and what counts as art is up to you. The body, too, Dunkan argues, is a "construct of identity," with shifting meanings in shifting contexts. If a European landmark can supply one of those contexts, he is not out to sustain a unique, indigenous Latin American art and Latin American architecture in reply, no more than the modernist photographers on view at MoMA for "Fotoclubismo Brazil." He values his birthplace for what he terms its multiform Caribbean culture.

Still, ignorance need not be bliss. Drawing on Edouard Glissant, a French writer from Martinique, Dunkan wants you to know that what you do not see may come back to haunt you. Like Glissant, too, he has played out the Afro-Caribbean diaspora in reverse, away from "the new world," knowing full well that it subjects him to western eyes that may refuse to see. That may seem an odd message right now, when Black Lives Matter rightly insists on the heightened scrutiny accorded African Americans, included unwarranted searches, arrests, and outright murder. Yet it matters, too.

Dunkan plays on both the discomfort in seeing and the ignorance. In other videos, of little more than his eyes and nostrils masked by makeup or his hand squeezing and peeling a fruit, he is hard to see. In a photo, I looked a long time at an odd, squishy shape before I pieced together his naked brown body squeezing into matching leather furniture. Even when he indulges in glitter, he may show off no more than his ankles. In his most unmistakably physical work, he does not appear at all. As for a larger context in morality or politics, he is not saying.

It is clear enough all the same. The Eiffel Tower is not the only metal or lattice frame here for the body. One assemblage consists largely of those nuts, another of coins or tokens from an unstated economy. (That slippery context again.) The black plastic ties that hold them together look spiky enough, but other sculpture in the shape of the body is more formidable still. You may not ignore it, but you will not wish to touch.

The work is haunted by nuts of all kinds, Dunkan included. How much, in the end, is he on view? The nutty assemblages could be armor, as protection, or the body itself. The sheer number of materials in one work has elements of both—laser engraved and cut PMMA, nylon hose clamps, after-shampooing, natural hair, and LED. But then "natural" for him is a construct, too. You may still distrust the showing off, but you had better appreciate the discomfort.

Shaun Leonardo ran at the Bronx Museum through May 30, 2021, Wardell Milan through October 21. Kenny Dunkan ran at Postmasters through June 19.