Dark Angels

John Haberin New York City

George Tooker

Had enough midcareer retrospectives celebrating youth and fashion? Not four months ago, Louise Bourgeois, now ninety-seven, ended her Guggenheim retrospective and a show of new work. Elliott Carter, the composer, turned out in December for his hundredth birthday at Carnegie Hall. Now George Tooker, too, is not just a part of New York history—or is he?

Not only did he live to receive the National Medal of Arts from George W. Bush, but a retrospective makes the case for his realism as very much alive. It shows him fully engaged in the politics of his time, including gay rights and the civil-rights movement. It shows his painting as increasingly personal, from his early urban scenes to softer curves and spiritual encounters. In his self-portraits in the lobby at the National Academy, one remembers most his clear, wide eyes. One may wonder, though: is their subject really alive, or has he returned from the dead?

Back from the dead

Born in 1920, Tooker studied at the Art Students League, when Reginald Marsh still taught. His early Coney Island scenes conjure up a city that was already vanishing. So does his best-known work, Subway, which entered the Whitney in 1950, just as abstraction was asserting a new American art. Its hallucinatory terrors look back to magic realism, a kind of Surrealism as seen through American eyes and American cities. Its leaders included Paul Cadmus and Philip Evergood, both born soon after the turn of the century, although some have also applied the term to René Magritte or Joan Miró. Tooker's retrospective begins traditionally, too, with that handful of self-portraits—one of them presented to the Academy as a requirement for membership.

Compared to René Magritte, his eyes might be seeing through to another world. He must sense at least one of its inhabitants, a black angel, who lays an open palm on his skull for inspiration. Or the eyes may belong to a man who has seen death at first hand. The artist himself describes the 1950 subway travelers as trapped in a kind of purgatory. In a later painting, Martin Luther King, Jr., returns from the dead, posed as Jesus in the Supper at Emmaus.

Tooker strips the scene to its basics, beyond even the early Baroque murkiness and clarity of Caravaggio. Jesus has only the bread, the table, and two disciples. All appear unnaturally solid, spare, light in color, and on a shallow stage, without Caravaggio's dramatic gestures and public scandals. Jesus has the artist's usual penetrating stare, but the eyes of his disciples remain inexpressive or blind. An explanation lies in the rounded perfection of that loaf on the table. Jesus has not broken bread, and the moment of revelation has not yet come.

Perhaps it never will. Perhaps Jesus is protecting his disciples from ever experiencing it. Tooker depicts emotional and spiritual communion as ambivalently inspiring and menacing, but more often close to impossible. The dark angel's gesture reappears in a painting from the 1960s, of a father with his young son. We see the boy, hair cut short, from behind. The father's fingers press in on his head as if sizing up a ripe melon.

When Tooker looks at people and politics, he finds a desire for spiritual release. Late in life, he converted to Catholicism. Still, release never quite works out to connection. The dark angel's wings flatten as they spread toward the picture plane. They could be cutting the artist off from this realm or the next.

In an imaginary portrait, a young Latin-American poet gives his benediction over the viewer, art, and nature. Crouching, he also appears trapped by the surrounding trees. His expression is ambiguously caring, needy, and afraid. Elsewhere, lovers appear not so much in a passionate embrace as in mutual suffocation. As they say, love hurts.

Little boxes

Tooker's anxiety, however moving today, is necessarily a period piece, and that has interest in itself. Think of the organization man and the bomb. Think of the fashionable existentialism of the 1950s. Sartre's No Exit, which made its Broadway debut in 1947, announced that hell is other people—or maybe other artists. Mark Rothko had moved to abstraction from his early subway scenes by 1949.

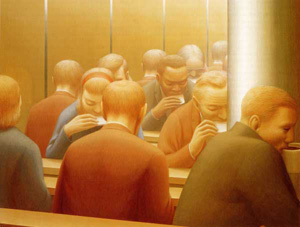

Here, though, hell is not other people. Hell is large enough and divided enough that everyone can have his or her own circle, although small and tightly packed. Everything and anything can divide them—subway phone booths, metal crates, office cubicles, lunch counters, hospital wards, or supermarkets reduced to a chaos of numbered aisles. Even the perspective tiling on the outside of buildings enforces divisions.

Mirrors and windows often serve as compositional devices, particularly in the self-portraits and bureaucratic interiors. In one late work, a still life on a window ledge shows Tooker's lifelong debt to the early Renaissance. It also brings a hint of nature, as part of his art's increasing calm. Just as often, however, mirrors and windows add confusion and isolation. They pile virtual barriers on top of physical boxes.

These divisions do not often allow human communication. Although I called them phone booths, one cannot say for certain that this element of subway architecture contains phones. No subway stairwell leads to the street, and the entrance gates have their prominent bars, like a spider's cage by Louise Bourgeois. In a still life, office mailboxes contain only blank, white sheets in place of letters.

The subway corridors rush back at left, right, and center as in a wide-angle lens, further dispersing the potential for communion. Only a woman at dead center stares forward—and with a look of crushing anxiety. A few at left are descending another stairway. Is it to hell? The descent appears quite voluntary. After the purgatory of this life, hell might represent a welcome change.

The hospital could just as easily be a morgue. Its stiff bodies with icy gray faces lie in parallel poses in parallel rows. A few people sit up or walk about, more or less freely and more or less at ease. Still, they, too, do not speak. Maybe they are mourners, or maybe they have not yet died. Or maybe they have awakened from the dead.

Diversity and gravity

If they have, they might finally have come into their own. Tooker himself does not seem to have a gloomy disposition, with good reason. He had early success in his twenties. He admired Cadmus, another gay artist and painter of Coney Island, and he was able to build on the latter's success. Subway made it into the Whitney Annual. The museum promptly snatched it up for its permanent collection.

He settled into Brooklyn Heights, then a far less exclusive neighborhood. In the 1960s, like so much of America, he turned from existential to political subjects, before the personal themes of the 1980s. His admiration of cultural diversity extends to his identification with that Latin-American poet. A portrait incorporates Arabic tiling. Still, it never gets easy to disentangle his empathy, pride, and hope from anxiety. The lunch counter is integrated (barely), but no one talks or even sees one another—or has much room to eat.

His commitment to American realism and American stories carries emotional ambiguity, too. In staking a position at a remove from Modernism, realists were looking for a greater clarity of vision and values. Tooker could take pride in his technique and artifice. However, realism also allowed an explicit disruption of expectations and an eerie weightlessness.

Tooker does more than pay lip service to art history. A self-portrait on paper emphasizes its polish, virtuosity, and tradition. It simulates the Baroque technique of white chalk on red, treated paper, suited to Peter Paul Rubens. And it does so with the still firmer and more demanding media of white pencil and red Conté crayon. Full-scale studies on paper appear finished, even when they stick to the quick, broad outlines of a composition and its perspective grid.

Tooker takes his characteristic medium, tempera on gesso, from the early Renaissance. He borrows a woman's head from Sandro Botticelli. However, his light, warm palette brings the medium closer still to its use in classical portraiture. And there, too, the technique points to a place between heaven and hell. Its dryness, as opposed to the atmospheric depth of oil on canvas, adds to the impression of stasis. Is it a coincidence that ancient Roman families so often used portraits to commemorate the dead?

Cornice, an early painting of a man on a ledge, also looks to both Tuscany and antiquity. For all the geometric detail of windows and cornices, the composition isolates housetops as in first-century fresco. As there, people and objects look solid, and yet gravity hardly rules. Will the man jump? Painting could just as easily doom or save him.

Bearing witness

Staring has another obvious association, too—bearing witness. If political art here looks so otherworldly, Tooker felt compelled to bring it back from the dead. It relates to Tooker's stylistic origins, in the social realism of the 1930s. It relates to his politics in the 1960s and his sexual identity. An awkward early painting shows men costumed in black, like cartoon supervillains, tormenting gay men with heavy sticks. They do not depart all that far from a hooded Klansman by Philip Guston in his WPA days or Wardell Milan now.

His realism, politics, and personal experience must all contribute to making his homosexuality more literal than in most postwar American art. One can debate endlessly how the theme appears at all for, say, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. However, Modernism lets them stress dislocation, displacement, loss, memory, and art's erotic charge as Tooker cannot. Conversely, Postmodernism might reclaim Tooker's art's realism and politics—but as retro and at one remove from reality. They make a retrospective newly contemporary, but as a kind of living history. If it looks campy here and there, such a story goes, all the better.

For all that, he is not just continuing social realism or magic realism as if nothing had happened. He was too young for that and too alive. He has too much interest in ambiguity and the stare to take unquestioningly what he sees. He may also hate to reduce sexual identity to sex. It would run counter to his native empathy, pride, and hope. Besides, he lived with the same man for about thirty years, until his partner's death.

He does not often share Cadmus's single-minded focus on male bodies and exaggerated physiques. His early Coney Island scenes have women front and center, like the sympathetic frightened woman in the subway. That painting of men beating men does not show Tooker at his best, and even there the emotional charge comes more through the rippling decorative surfaces of the buildings behind them all.

He is not, then, anywhere close to the public gay life of Robert Mapplethorpe or the hidden life of Anthony Blunt. More often, homosexuality shows up indirectly—though the politics of diversity, the decorative style, and compositions centered on human bodies. The black angel or, in another painting, a naked black man may relate to the stereotypical association of the black male with virility. The man reaches upward like a Georgia O'Keeffe flower or a vision out of Arthur Dove, a very modernist understanding of sexuality after all.

Tooker had his one big hit in 1950. Inevitably, that makes his painting uneven, as the critical cliché goes. It also makes his work more rewarding when one sees it in a mass. When a painting sticks out, as on an ordinary day at the Whitney, it can look a little hokey—and some works, such as Cornice, look very hokey. This once, though, he gets to look just slightly out of touch with his time, like his stare. That alone makes for a living retrospective.

George Tooker ran at the National Academy Museum through January 4, 2009.