The Music of Identity

John Haberin New York City

Julius Eastman and Glenn Ligon

Otobong Nkanga and Nour Mobarak

Ever wonder why pianos are black? Oh, sure, they come in white for the cheesiest of stars and Vegas acts, the kind that stop just short of dancing on the keyboard, but still with a touch of class.

Julius Eastman was both cheesy and classy enough in his day to title a composition Evil Nigger, neither reigning in hell nor serving in heaven. He was, though, a serious avant-garde musician, and don't you forget it. Glenn Ligon, for one, remembers. He builds an exhibition around that composition along with baby grand pianos and his own celebrated paintings,  as the very image of blackness. If piano keys are mostly white, you will understand. You had better.

as the very image of blackness. If piano keys are mostly white, you will understand. You had better.

Still wondering about those piano keys—all the more so if you enter the Tribeca gallery between their bursts of activity, in silence? To be sure, music is a African American's cultural heritage, but can music (or just plain noise) become African American sculpture or an installation? Otobong Nkanga and Nour Mobarak make use of choral music and opera to fill ungainly museum spaces at MoMA. And they do so to evoke not just Western music but an African heritage and its loss. This is the music of identity, but an identity that may be hard to make out amid the darkness. Is this the sound of African American art?

oLive evil

If you cannot decipher that image or pierce the silence, fine. These artists dare you to listen up. Both, too, know their way around jazz, where Miles Davis had his Live Evil. Ligon places a neon sculpture at the very center of the installation, with the opening syllable of Toni Morrison's Jazz repeated and scrambled. Sth already sounds like a whisper akin to silence. But then his art often bears the marks of its own defacement or, deconstruction might add, erasure. The French for "under erasure" in Jacques Derrida is in fact sous rature, or scratched out.

Eastman's composition sounds jazzy enough, too, when you can hear it. Just past the sculpture stand four pianos, with no performer in sight. Three, though, are Yamaha player pianos that kick in once a hour. It is worth the wait. Can music be at once lilting and brooding? His layered riffs on a single note sure is, and maybe a black artist has to be. As for the fourth piano, it is an antique for that touch of class.

The show also includes a print based a later composition, Thruway—where, you might say, the traffic barrels on through. Eastman's rhythms guide a second neon as well, a wall sculpture, with the word speak blinking on and off in response. It appears a good dozen times within an oval, on top of the blinking, for repetition twice over. Ligon, now in his sixties, is a natural collaborator, who takes pride in his blackness but betrays uncertainty with each and every word. Ligon's Whitney retrospective in 2011 seemed to grow out of a single text painting, Today I Am a Man. Rather than start over, allow me to refer you to my longer review then.

He was deceiving himself and no one. As an adult he was always a man, and white America could always deny it. He, in turn, could measure out the toll with repetition and erasure. A large text painting is pretty much illegible, and a still larger one approaches monochrome black. It effaces itself with coal dust, just as coal effaced working-class lives. The word America appears in large type upside-down, backward, and burnt.

Eastman, who died in 1990 at age fifty, gets a full wall for sketches and prints hung high and low. His words, too, could be confessional or a lie. If you cannot read them at that height and cannot make sense of what you can read, it happens. The score to Evil Nigger hangs by the front desk. It could serve as a score should, to lean on, or as just a teaser for his larger career as composer, pianist, vocalist, and conductor. Sth could also be the sound of words caught in his throat.

The gallery has featured blackness before in shows of Bob Thompson, Arthur Jafa, and Tiona Nekkia McClodden. Her title, "MASK / CONCEAL / CARRY," could speak for them all. The space risks becoming making a ghetto for so prominent a Chelsea dealer, but I am not complaining. This is still Tribeca, and Ligon is exploring the limits of community and confrontation. He is also finding himself newly at home in collaboration. This is not one but two evil niggers.

The big picture

Otobong Nkanga invites you to approach her work in stages, and each stage opens onto larger and larger vistas. She calls it Cadence and speaks of it as the cadences of life—but human life, she adds, is only a fraction of the cosmic picture. I want to say a negligible fraction, but it is the part that humans feel most keenly. In fact, the big picture looks indelibly marked by humanity. Whether that is a good thing is hard to say, but it is impressive all the same. On commission for the outsized and unruly atrium at MoMA, she does her level best to run out of space.

There is no right way to tame the atrium, the worst element of MoMA's 2004 expansion, because no one, however adept, really can. I still think of it as little more than a shopping mall whose chain stores have gone out of business. Recent installations, though, have refused to get lost in its waste of space. They can let classic works, like Rhapsody by Jennifer Bartlett or New Image painting by Susan Rothenberg, run its full length. They can play on the furniture and function of the museum itself, like Amanda Williams—or recreate city streets and fire escapes as a gathering space, like Adam Pendleton. Nkanga works on a still larger tapestry, literally and figuratively.

A single image sets the scene, draping down across an entire wall of the atrium, but not the center wall. Is that to keep it from dominating the rest? Rope sculpture hangs down from above, too, coming to rest on shiny black sculpture of craggy rocks. Bulges punctuate the rope, like bulges in wire sculpture for Ruth Asawa. Downright small work has the remaining walls—relief paintings, with caked surfaces like dried earth. They are largely monochrome, even when interrupted by unreadable text.

Or is it merely to give the tapestry the atrium's largest wall. (Who knew that the walls differ in size?) It is a landscape, but not a familiar one from planet earth. At bottom, shimmering white curves outline what could be plants or waves. At top, orange fills the sky in bursts, like galaxies without stars or bombs bursting in air without the patriotism. About halfway up, a couple seen from behind contemplates the scene. They seem to take it all in without a care for the damage that people can exact.

Then, too, Nkanga might have chosen that wall because you cannot see it until have entered. Rounding the corner from outside, you first encounter the sculpture and a tempting glimpse of the small paintings. Once inside, you can stumble around fairly uncluttered space. It is officially the Marron Family atrium, and no doubt "family" refers to the donors, but parents do let their kids run about. You have already accumulated a reserve of impressions, varying in size, texture, and color. And then you can turn to discover the cosmos.

You can hear it as well, although not the explosions. A chorus chants something ethereal, while a single male voice repeats just one cadence. Nkanga hardly minds if you cannot understand a word of it. She is not spelling things out. Born in Nigeria, she works in Belgium, but nothing I could see alludes directly to her heritage, and the couple in the tapestry is probably white. And I do wish the work cohered and the text made sense, but everything seems to emanate from the landscape.

Networking with the gods

Nour Mobarak may not sound like a candidate for nostalgia. Born in Cairo, she identifies as a Lebanese American, works (mostly) in LA, and seems no closer to settling down, no more than a sadly conflicted world. Among her media are fungi. Yet she sees them as an emblem of the geopolitical struggles that divide but also give hope. They nestle in soil, laying down mycelium, much like roots. She must like it, too, that the word for its fibers, hyphae, nearly rhymes with Daphne Phono, her studio installation at MoMA.

Her work stops just short of nostalgia, too. Who can remember when a proper home put a phonograph record on the phono—the "talking phonograph" that Thomas Edison invented long ago? Contemporary DJs and a retro admiration for turntables and vinyl cannot make the old vocabulary any more vivid. Yet Mobarak has many time frames, in a disorderly room of "singing sculpture." And what they are singing is Dafne, a candidate for the first opera, nearly ten years before Monteverdi's Orfeo. They may not sing in anything close to harmony or unison, but those are to be found as well. "These are," she insists, "the cadences of life."

Her work stops just short of nostalgia, too. Who can remember when a proper home put a phonograph record on the phono—the "talking phonograph" that Thomas Edison invented long ago? Contemporary DJs and a retro admiration for turntables and vinyl cannot make the old vocabulary any more vivid. Yet Mobarak has many time frames, in a disorderly room of "singing sculpture." And what they are singing is Dafne, a candidate for the first opera, nearly ten years before Monteverdi's Orfeo. They may not sing in anything close to harmony or unison, but those are to be found as well. "These are," she insists, "the cadences of life."

The opera itself can claim a resolution, at the expense of its heroine, Daphne. And it, too, has widely separated points of origin. Greek myth spoke of the sea nymph, or naiad, and her pursuit by Apollo, but it has survived thanks to Roman poets long after like Ovid. It may have grown more wistful in the process. Greek gods, particularly Zeus, had a sorry habit of lusting after lesser beings, stirring up jealousy among the gods and wars among humans. Ovid's Phoebus (or Apollo) cries out to Daphne. He means no harm, for he brings a god's love.

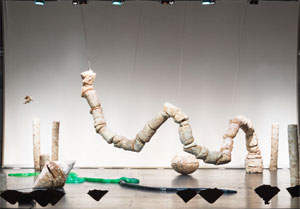

In the end, he transforms her into a laurel, a symbol of Apollo himself. Could the transformation explain the contrast between Mobarak's snake-like sculptures? The largest winds through the air, while a shiny green one lies flat to the floor. Do fungi contribute to either one? The first has a thick, mottled surface like discolored concrete, but its snaking and mottling could echo her dreams of roots. She describes it as akin to a biological system, a technological network, or linguistics.

I would add song. Not that Daphne Phono sounds the least like early Baroque opera. Unlike Monteverdi's breakthrough from modal to tonal music, with key changes and a twelve-tone scale, it sounds more like an incantation. I am still uncertain what to make of it or to name its language. Museum displays of sound art run counter to the arc of musical theater anyway. You can, after all, enter in the middle and exit at will. For once MOMA's studio takes down its front wall as if to encourage you.

The remaining objects, roughly pots and pillars, share the rugged shapes and colors of concrete or stone. Wall text identifies them with the other characters in the story, including Venus and Eros. (Hey, someone had to set off a tragic love.) Never forget, though, that Apollo was the god of light, music, and beauty, which the myth in turn brings to love. As war in the Middle East widens, Mobarak must hope that they will reach there as well. She gives peace a voice, if not any more of a chance.

Julius Eastman and Glenn Ligon ran at David Zwirner/52 Walker through March 22, 2025, Otobong Nkanga at The Museum of Modern Art through June 8, Nour Mobarak also at MoMA through January 8. A related review looks at Glenn Ligon at the Whitney.