Becoming Modern

John Haberin New York City

MoMA: The Lillie P. Bliss Collection

Hilma af Klint

Imagine the Museum of Modern Art without The Starry Night. Now imagine what it would have become without its founding director, Alfred H. Barr. Not easy, is it? At one point, a turning point, as the museum approached its landmark opening in 1929, the two were at odds, and just try to guess who won.

The outcome brought the museum that much closer to a canon for modern art, thanks in no small part to Lillie P. Bliss. Now MoMA gives her and her collection their due, to put its finger on what was at stake. Ah, but the museum also finds room for a woman that both curators left out—an artist with a most old-fashioned fixation. Artists have long delighted in flowers. It puts to the test their powers of observation and commitment to nature. It brings out the possibilities in media such as watercolor, with its fluid line and still more fluid color.

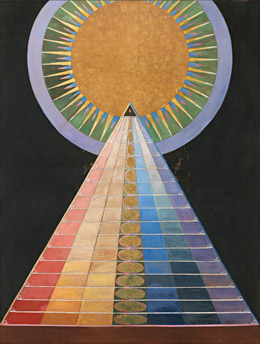

All well and good, but Hilma af Klint wanted more. She asked "what stands behind the flowers." A show of that name asks with her, at MoMA, and it reinforces the case for af Klint as a progenitor of abstraction. Ah, but then what lies behind that? If your answer is nature, she would not mind a seemingly vicious circle. She felt pure form as essential to both.

MoMA without modern art

Few exhibitions rewrite history, although more than a few try. With just forty works from the Lillie P. Bliss collection, the Modern rewrites its own history. Generations, me included, have learned how a young professor at Wellesley College gave modern art a defining history, one that lasted the rest of the century—and, to its credit, one that MoMA itself has worked hard for a while now to revise. Alfred H. Barr created a canon that started in Paris and found its fulfillment in New York, on the cutting edge of the present every step of the way. That is why he planned the new museum's opening show on Fifth Avenue to stick to then contemporary American art. It took just three women to shoot it down.

As MoMA tells it, Bliss, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, and Mary Quinn Sullivan were its true founders—with the indulgence at most of John D. Rockefeller himself. The three got the idea and contributed its core. Sick and tired of the crowds in front of The Starry Night, which is not even modern? Now you can see it much as it once stood in a private collection. Bliss also allowed her work to be sold to fund new acquisitions, a museum no-no today, but that helped pay for such stalwarts as Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, by Pablo Picasso, as well. (That work still hangs in the main galleries.)

The founders saw a growing interest in the art that had shocked New York in the 1913 Armory Show, where Bliss first publicly exhibited her collection. She showed again at the Met, but she was not a precocious or instinctive collector. She met Arthur B. Davies, a painter of nudes and landscapes, and John Quinn, among the first collectors of modern art. Both had her looking back to the last century, with the Symbolism of Odilon Redon. She collected Georges Seurat as well—like the precision of Seurat drawings in Conté crayon in black. She found a new freedom, though, well into her fifties, with the death of her mother, who had needed no end of care.

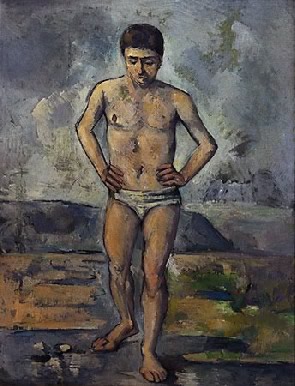

And that freedom had her looking to the present—and to a future museum for modern art. I, for one, could easily leave The Starry Night to Vincent van Gogh on loan a year back to the Met. I could not imagine the Museum of Modern Art, though, without Paul Cézanne. No one else so embodies a vision of modern art as rigorous but constantly probing, even as the artist all but despairs of finding completion. And that vision was Barr's. Still, Bliss collected work spanning Cézanne's career, including Uncle Antoine, Pines and Rocks, Still Life with Apples, and the large Bather.

I still marvel at how his uncle plays the artist himself, how firm the bather seems, and yet how evanescent he is as well. I still marvel at how the weave of a forest both invites and defers the sun. I still marvel, too, at how the pattern on a cloth seems to tumble out onto a table with the already unstable apples. Bliss had caught onto something, and Barr must have been a welcome discovery as well. Still, she and her co-founders had to object when his planned opening show excluded Europe. Maybe her relative conservatism was at play, too, in starting with Post-Impressionism, but not altogether. Still, the women did not have to threaten a veto to change Barr's mind, for he knew all along how much lay at stake.

The show will never be "major," and work will return to galleries for the museum's collection when it is done. It includes letters, a telegram, newspapers, and the guest book from the museum's opening for those who want to rewrite history for themselves. To the end, though, Bliss was still helping the museum keep up with its times. She bought Paul Gauguin woodcuts and a grandly flat portrait by Amedeo Modigliani. She bought Picasso's Woman in White and the view out a window by Henri Matisse with an empty violin case and sunlight's silent music. She died in 1931, never to see MoMA in its own building just blocks away from its first home, the one she knew.

Behind nature

Hilma af Klint was on hardly anyone's radar when the Guggenheim served up a 2019 retrospective, but then neither was abstract art when she began to make it. She had a reputation, to the extent that she had a reputation, as a Symbolist, and that could upend the history of abstraction. Her first nature studies at MoMA date to 1908, when itself was barely in flower, and the Swedish artist may not yet have heard of it. Born in 1862, she came late to the job, but she had an interest in flowers even as a student, in essays and notebooks. It took a direction not even she could have expected.

She kept her studies of nature and design separate at first, but barely. Her first dated studies could be symbols in an unknown code. Curves break away from larger circles, condensing into bulbs, buds, or seemingly nothing at all. Undated studies keep their eye on the ground and the forest canopy, with ferns and soil running densely the width of the paper. You are likely to remember them for their texture without quite known whether that derives from botany or art. Subsequent studies, starting in 1918, focus on the radiance of circles and squares without a flower in sight.

She kept her studies of nature and design separate at first, but barely. Her first dated studies could be symbols in an unknown code. Curves break away from larger circles, condensing into bulbs, buds, or seemingly nothing at all. Undated studies keep their eye on the ground and the forest canopy, with ferns and soil running densely the width of the paper. You are likely to remember them for their texture without quite known whether that derives from botany or art. Subsequent studies, starting in 1918, focus on the radiance of circles and squares without a flower in sight.

Still, her drawings have a single impetus, and within a year or two they came together at last. A flower study follows the vertical course of a branch or stem. So, to its side, do small colored circles, like stills from a cinematic color wheel. More often, she pairs flowers with an actual color wheel or rectangle, with diagonals that need never meet. Are they the components of art for art's sake—like color wheels or nested squares in the days or Josef and Anni Albers—or even today? Do not be too sure.

In those same years, she was pursuing comparable shapes in painting, as suns, pyramids, and altarpieces. They make a point of their radiance, but are they bringing a heavenly vision down to earth? Without the obligation to compose a major painting, the madness is all the greater in drawing. She has a parallel, too, in the painstaking course from nature to abstract art in Wassily Kandinsky. Yet she is less inclined to leave flowers behind, not even when, with her Atom drawings, the lure of science shifts from botany to quantum mechanics. She worked in series and soon had her largest, Nature Studies, and she spoke of all her work as a botanical atlas.

Notice, though, how nature keeps its distance, behind the curtain behind the curtain. Some studies allow words back in, as in her student essays, but perched on spirals. In the show's last series, radiance becomes the aftereffect of an explosion. Here she unleashes the fluid nature of watercolor, with shades of blue, yellow, and especially red changing its shade as it covers a sheet. Notice, too, though, the humility, even banality, of her approach to nature, much as in her early ferns and fallen leaves. If a fly or an ant enters the scene, it counts as both nature and art, too.

She may seem to have outstayed nature's welcome, as modern art was coming to be. The popularity of nature studies reflects the ideals of Romanticism, from John Constable to Beatrix Potter, in observation and expression. It comes with a moral, too, ever since flowers in Flemish still life became a parable of decay and death. Still, af Klint refused all that quite as much as Modernism. Swedish winters hang on way too long for her to abandon the first signs of blossoming. What lay behind the curtain was the impress of the curtain itself.

The Lillie P. Bliss collection at The Museum of Modern Art through March 2, 2025, Hilma af Klint through September 27.