Impressionism Without the Color

John Haberin New York City

Georges Seurat: The Drawings

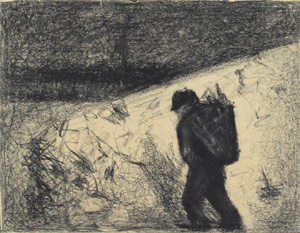

Georges Seurat saw the world in black and white. At least he drew it that way, and a survey of his drawings shows him at his most rigorous and personal. He seems determined to press black Conté crayon to paper until he has squeezed every last thing out of nature except the light.

Vision, structure, or pure color

One often thinks of drawings as opposed to painting in just that way—as merely black and white. Leonardo took to the streets, pencil in hand, as part of his training, discipline, and endless curiosity. Artists had to trace anatomy or a perspective grid over and over until they got it right. Even Vincent van Gogh loved monochrome, with his quill pen and brown ink.

Georges Seurat, however, stands for something, for color. Call it Pointillism, Divisionism, or Post-Impressionism, the term coined by Félix Fénéon. Call it what you will, but it supposedly reduces painting to dabs of pure hues, unmixed and with nothing in between. Many an artist wishes paint on canvas looked as good as when squeezed right out of the tube. For Seurat it does.

Seurat died of diphtheria at age thirty-one. Even Raphael lived longer, long enough to find his way to the High Renaissance and then even Mannerism. Seurat pursued one thing, but it pointed everywhere. For Paul Signac, realism had become a science of vision. For Camille Pissarro, painting had achieved a structure and solidity that Impressionism lacked. For Henri Matisse, a generation younger, this art set color free with its own laws—or lawlessness.

One should feel the shock of Seurat's drawings, or one has missed out on the experience. The Museum of Modern Art helps, by resisting the urge to include his finished paintings along with their preparatory studies. It does include some oil sketches, including a spooky version of the painting everyone now knows as "Sunday on the Park with Georges" without its familiar cast. Figure studies, including studies for the monkey and the dog in mid-leap, have their own sheets, where they appear much more domestic and spontaneous. The larger scene looks so realistic and yet so lifeless that the only figure, a swimmer, could almost be drowning. One could call it A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte without the Sunday afternoon.

That already suggests some reasons for all the black, and they parallel what other artists found in his color. First, again, Seurat drew because he could draw fast, and he was in a hurry. He exhibited that warhorse at only twenty-six. Second, as Signac saw, he sought the essence of light, and how better to analyze and purify it than in black and white? Third, as Pissarro felt, he cared about moments beyond one Sunday afternoon, and he never gave up the academic tradition of working things out on paper first, not just painting en plein air. Fourth, as Modernism and Matisse saw, he set his medium free to fill every corner of the image, with or without its ultimate subject.

More interesting still, all those contradictory motives co-exist just fine, without getting in each other's way. On one sheet he writes, "Harmony is the analogy of opposites"—not resolution or reconciliation, but some kind of correspondence mysterious enough to leave poles apart. The Modern arranges his career logically enough. First come opposite walls for academic work and sketches from life, then opposite walls for figure and country, and finally separate rooms for the path to each major painting. Here, too, however, opposites attract. In fact, they interpenetrate.

Shades of black

Okay, I lied: Seurat does not work strictly in black and white, even aside from the oil studies. An early sheet has colored pencil—naturally enough, the three primaries. Toward the end of his life, he overlays highlights in other media, typically in blue and white. They remind one that, scientific or not, his mature oil paintings do not rely on red, yellow, and blue alone to construct light and shadow. They have green, purple, and plenty of white on top.

To call the works in Conté crayon black and white misrepresents them, too. One might better speak of black alone. Many an artist treats drawing as mixed media, and Jean Antoine Watteau defined his own virtuoso combination of three chalks. Compared to Seurat, however, even black-and-white photography has way too many shades of gray. He does not trace across or stipple a sheet. He burrows into every inch of it.

Artists traditionally used Conté crayon, a mixture of graphite and clay, for its discipline and precision. Unlike Picasso in black and white, Seurat values its softness and its range. He can sharpen it, thicken it, or smudge it. It can build up to the solidity and flight of a locomotive at top speed, the haze of its smoke, or the harsh, jagged edges of the houses, tracks, and sky. Shadows can have depth or sudden leaps. Even with Ad Reinhardt, one may never see so many shades of deep black.

That leaves the white of the paper as one pure shade with varying degrees of luminosity. It has much less space than with most artists, but it can penetrate anywhere. Typically, Seurat starts with faint outlines or firm, short parallel strokes. These define a figure and also allow him enough control to leave a near-perfect circle of moonlight. Then he goes to town, but often with a distinct halo of white surrounding a figure, lifting it forward, and adding to its presence. At times he finishes by scraping off or erasing a spot, for the most startling highlights of all.

His accomplice is the handmade paper. Michallet paper comes in fairly large sheets, and he tears off whatever dimensions he needs. It has a smooth side, like felt, and a ribbed side, and he prefers the latter. The academies taught one to respect and to work with the paper, but not to this extent. His black brings out the ribbing, as a kind of preparatory grid, then largely effaces it. By the end, its texture creates a kind of Pointillism in black and white.

Again Seurat's technique brings out contrasting aspects of his work. He can come across as academic or impulsive, the realist or akin to abstraction. His care for the material nature of the paper would fit just fine with late Modernism's talk of the art object. This sheet of paper is literally a shallow space, even before the artist gets involved. And does he ever.

In the zone

Of course, to place Seurat in a space between tradition, Impressionism, and Modernism is no more than to place him in his time. He was a toddler when artists headed to Barbizon and a little boy when Edouard Manet shocked Paris. He was fourteen when Claude Monet drew others to Argenteuil.

The Modern picks him up at eighteen, three years after the first Impressionist exhibition. He is preparing for formal studies, with mythological scenes and copies after Classical statuary that would surely have earned a passing grade. The first command the sleek outline of J.-A.-D. Ingres. The second show a fine modeling of anatomy. His pencil shading has a hardness akin to silverpoint.

The facing wall could show the dark night to his day job, except that it is his life. He finds poverty on the streets and art in the dance halls. He finds men paying the price of war, does his own brief service, and returns with thoughts of the academy behind him for good. One gets to thumb through his sketch books with a touch screen for more. The Morgan Library already has computer terminals in its spacious Renzo Piano lobby, and the idea is bound to spread. Here it really does help with the small, thick bound books only a couple of inches tall, and it lets one imagine that one is flipping the pages.

Already, the tidy categories have broken down. Seurat takes the mythological scene from his imagination, and he gives anatomy fleshy folds of less than ideal proportions. Meanwhile he finds stasis in the poise of a dancer or a homeless person huddled in sleep. When he draws a drummer pounding away, he stills the action and conveys his appreciation of the drum's perfect cylinder. Till the end of his life, he prefers scenes of motion, instability, or exhaustion, even in the midst of middle-class leisure. Yet he describes it as an assemblage of patterning.

By the second room, he has fastened on his media of choice, and his explorations go further, in society as well as in art. The opposition of town and country may help in comparing subjects. But here, too, he does not simply take sides. In practice, he is documenting a whole new Paris, "the Zone" between city and suburbs.

As Baron Haussmann created the great boulevards connecting intimate and elegant side streets, as seen by Charles Marville, he was pushing the working class and industry to the edge. That division came to the surface again just a couple of years ago, with rioting. However, Seurat preferred edges all along. His art lives in a zone, open to forces from all sides. It is significant how often he portrayed the theater and light sources within the work—artifice and artificial light.

Objectivity and intimacy

Mostly he stays in the Zone, while Monet and others leap from the Seine to the suburbs. Where Monet painted a departure point, in a great train station, Seurat sketched the train passing factory sheds. Where Monet followed the middle class away for the weekend, Seurat found it on that island east of the city's center. Even there, smokestacks provide a backdrop, like that of a stage set, but large enough to contain multitudes. Maybe that scope and artifice help explain why La Grande Jatte has proved so difficult to interpret. Critics have found everything from modest urban comforts to ostentatious displays of wealth like that pet monkey to prostitutes trolling for clients.

Formally, Seurat navigates between two and three dimensions. He isolates the outlines of a dancer or the fullness of a dress's bustle, and they can seem as flat as patterns on a vase or as full as statuary. He often takes someone from the rear, just as Giotto used rear views to create depth and to draw emotions from a figure's bowing or trembling. He likes buildings in perspective edge-on, and the trapezoids do not easily resolve into cubes in space. A drawing of Haussmann's great spaces looks so open that the Place de la Concorde becomes unrecognizable.

Then the light fills everything. Take away the objects, and the light would vanish, but the light alone defines the deep space of Western painting. The oil sketch of La Grande Jatte looks even more realistic without the people. The other Post-Impressionists lost something when they flattened things out.

Emotionally, too, Seurat lives on the edge. Monet faces up to modernity well enough, more indeed than early modernists. He also finds joy in it. His almost abstract but also deadly accurate London skies need the fog of the industrial revolution to exist. His train station, with clouds of smoke billowing up to the glass and steel enclosure, conveys excitement. Seurat's darting Conté crayon accepts the ugliness of soot, freight yards, and ragpickers. He updates themes like Courbet's stone breakers and Millet's reapers, but without ennobling them.

I find something ambivalent, too, in Seurat's point of view. He can seem not simply formal but ice cold. I cannot think of a less sexy portrayal of a woman's waist than Seurat's profiles. He rarely makes eye contact, even with his own family. At the same time, he has more intimacy with his subjects than others of his time. He allows grownups to toil and children to suffer.

The drawings enhance that ambiguity, which may explain why they show Seurat at his most tender, accurate, and memorable. The black casts a haze over everything, but the luminosity invites one up close to penetrate it. One feels closest of all in his portraits, including a friend at work on his own art, his mistress in near squalor, or his mother embroidering. This art invites contemplation, and that, too, can imply objectivity or intimacy. It also leaves one unsettled, like Seurat in the Zone. Instead of shades of black, one could think of shades of blackness.

"Georges Seurat: The Drawings" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through January 7, 2008. A related review looks at "Seurat's Circus Sideshow."