Between the Covers

John Haberin New York City

Dialogue and the Artist's Book

Beyond the Visible: Odilon Redon

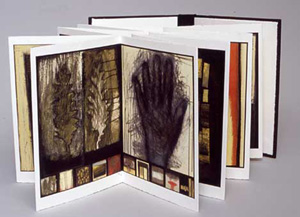

The artist's book can so easily get lost in the space between art and printed matter. As art, it has a way of hiding among other small objects in a display case, more than half its images unseen, the others vying with words that insist on running from left to right. As a book, one may never get to hold it in one's hand, to turn its pages, to discover its stories, and to take them for one's own.

That tension, however, also makes books a natural for the chaos of art these days. Who does not face hybrid media, word painting, the revival of craft as fine art rather than "woman's work," museum displays of fashion, and the puzzle of art in an age of mechanical reproduction?

"Dialogue," an exhibition with six different locations for an artist's books, does a particularly good job of bringing out their eclecticism. An actual dialogue among the artists themselves helped further to probe what it means to read a work of art. So does an exhibition of Odilon Redon in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Redon's lithographs to accompany a novel function as independent prints, but they help one see text and art alike as far less linear and retiring.

Making book

With "Dialogue," a curator's sensitive response to each New York venue underscores the puzzle and possibilities of hybrid media. For starters, but only for starters, books can add images to words or give greater space to images than a single print can allow. At the Abrons Arts Center, prints most often hang traditionally, on the wall. Yet a silkscreen Portrait of a Mermaid by Desirée Alvarez suspends a white curtain right across the gallery space. Anne Gilman lets unnumbered "price tags" overflow a white box, as if to attest that the value of things and the images they evoke will always overflow their origins, and Miriam Schaer suspends little girls' dresses above a floor of autumn leaves. A few weeks into the show's run, air circulating from the heating vents added its own fashionable narrative to the empty dress.

At the Center for Book Arts, art has to share a floor with an active school and workshop. The old-fashioned letter presses make it hard not to think of books as objects in a tradition of their own, like the book covers of my childhood by Elaine Lustig Cohen. The display cases include everything from an upright, unfolding urban panorama by John Ross to a paper building on paper stilts by Kumi Korf and a wall by Maddy Rosenberg, its stone unfolding in soft blue. In the third New York segment, in downtown Brooklyn, the glass-enclosed Humanities Gallery of Long Island University has a way of suspending art itself between image and object.

The eclecticism makes for a good lesson in technique after years of modern drawing, including the usual reproducible media as well as monoprints, computer sketches, and handmade work. Rosenberg, who somehow managed to curate all this (even before opening her own gallery for artist books, Central Booking, often with themes of art and science), even contributes flip books and the tiny drawers to hold them. The exhibition's richness also brings out the many varied associations with books themselves. Shirley Sharoff nestles sheets of thick, folded paper as if to make palpable the leaves of a book. Rene Lynch wraps Prospero's Island in lightweight colored paper, like a stone. I thought of Prospero himself at the end of his story, promising to "drown this book."

One can think of the exhibition as a reminder that illuminated manuscripts and their imperial splendor such as a Medieval Housebook and Le Livre de la Chasse predate Western museums—and that artist books continue to evolve. Alvarez calls another silkscreen curtain A New Book of Kells, updated with cell (or perhaps kell) phones, and Hilary Lorenz designs Phrenology with the size and weight of a medieval text. However, Lorenz's Predetermined Heart incorporates not the text of a poet but genetic base pairs, and both Louis-René Berge and Luce embellish recycled VCR boxes. I felt grateful for the absence of goth CD covers, but I suppose an exhibition would be incomplete without a graphic novel, and David Lantow supplies one.

Besides images and words, art and poetry, the title "Dialogue" refers to New York and Paris. Half the artists are French—ironically, including one born in New York State—and the remaining three installations unfold in Paris, sharing the freer landscape of an artist's book. Generally speaking, the French give greater weight to text, with a more traditional division between word and image. They also trust more to shades of gray and provide more frequent evidence of pressure by the artist's hand, as by rubbing across images and wet ink.

Between these visual choices and a more conservative style, rooted in early Modernism, their themes more often suggest reproduction as a trace of absence—in Florence Hinneburg's title, Empreinte de l'Absence. The Americans run more to color, the natural world, and urban realism. However, a number of the Americans have adopted a subdued palette for the occasion, like Sarah Plimpton's Black Palette or the ghostly undersides of Douglas Bennett's Coney Island roller coaster. Either there really is a dialogue, or Americans are just better at learning and experimenting.

The vanishing act

Will others welcome the experiment? Will the trace retain the power of an artist's living presence, and should it after Modernism? Can printed words survive as detached art objects, as in the work of Simryn Gill? Is there really that big a gap between books and conceptual art? No doubt every artist faces those questions, but few understand as deeply as printmakers the problem of gaining their due recognition.

Reviewing Odilon Redon at the Modern, The New York Times noted that most of its 140 works would fit in a drawer. Of course, stacking them all might take its toll on the fine charcoal and thick pastels, but the Times is not really advocating new standards for conservation. Rather, Holland Cotter is grappling with Redon's "self-effacingly small, visually hyper-discrete" art. Actually, Redon devoted much of his career to lithography, and his illustrations would dwarf many a coffee-table book. However, even today, artists who devote their lives to prints know well the frustration of competing for respect and attention.

Reviewing Odilon Redon at the Modern, The New York Times noted that most of its 140 works would fit in a drawer. Of course, stacking them all might take its toll on the fine charcoal and thick pastels, but the Times is not really advocating new standards for conservation. Rather, Holland Cotter is grappling with Redon's "self-effacingly small, visually hyper-discrete" art. Actually, Redon devoted much of his career to lithography, and his illustrations would dwarf many a coffee-table book. However, even today, artists who devote their lives to prints know well the frustration of competing for respect and attention.

One evening during the run, several contributors to "Dialogue" gathered at Abrons, on the Lower East Side. They talked about what drew them to the media and what still sets them apart. They spoke of the sense of play, when slight changes can alter an impression and different printing techniques keep opening new possibilities. They spoke of the immersion in technique, as itself a pleasure beyond simply painting in words, along with the pleasure of holding the art object in one's hands.

They spoke of collaboration with other artists, whether in the shared space of printing facilities or in trading prints among themselves. Multiple impressions, some felt, quite generally strike a blow for artistic democracy, compared to exclusive and more expensive media. However, they in turn command less regard and a lot less income—a fate long shared with photography as well as design, craft, and other such supposedly "women's work." The artists I know do not sound self-effacing, small, and discrete, and I love them very much for that. Yet dealers so often treat their brand of magic as a vanishing act.

Other artists may yet find these issues oddly familiar. One could argue that claims for the media mean only that printmakers have found what they most want to do. Painters and welders treasure the touch and smell of their work, too, and digital art requires perhaps the ultimate kind of patience—debugging. Art itself represents the ultimate form of adult play, even apart from the turn these days toward work that resembles video games or overpriced playground sets. An artist in Brooklyn recently turned his gallery into a toy city, invaded by spider-like space aliens. Boy, is he having fun, even if you are not.

The assault on the aura of the work of art should sound familiar as well. Most famously, Walter Benjamin hailed mass reproduction, decades before Andy Warhol silkscreens, Warhol self-portraits, Warhol in camouflage, Warhol's influence, and Robert Rauschenberg's combines, and Rosalind E. Krauss found a postmodern paradise even earlier, in Rodin's endless casts. New-media artists have talked of digital dissemination and open-source coding as alternatives to the gallery system. Conversely, I found it interesting how the panelists simultaneously clung to the artist's books for something older and more intimate, the feeling of a book in a digital age. Should one see the conflict as intractable or exhilarating? For a reminder of little artists this talented will settle for mere discretion, consider for a moment an older model of printmaking, in the hands of Redon.

Architect of the imagination

Imagine, if you can, Odilon Redon as an architect. If you feel like laughing, so apparently did his teachers. The artist of ghostly figures in a dark, undefined inner world first meant to design real spaces for real people, and it did not go well. He had little success, too, as a student of Jean-Léon Gerôme. The artist of demons in the mind's eye seems singularly ill-suited to the Salon painter's leaden realism. The artist who rubbed, stumped, and nurtured so many shades of black has little in common with an academician's firm outlines and lavish color.

The Modern calls its mini-retrospective "Beyond the Visible," and Redon did become a rebel against realism. The principal exponent of Symbolism in art, admired by Paul Gauguin and many modernists, he discovered his themes in nineteenth-century poetry and fiction, including a novel often known in English as Against Nature—as well as his own troubled life. (One might better call J.-K. Huysmans's tribute to fin-de-siècle alienation Against the Grain.) Still, one refers to the visual arts with good reason, and I should not laugh too quickly at his origins. His first works on paper attempt crisp, bright seascapes after early Camille Corot. Even in his mature art, he remains like Gerôme an illustrator of the exotic, as a window onto human desires.

No doubt only the Modern could assemble a career survey from its permanent collection. Of the more than a hundred works, many come from a single recent gift, the Ian Woodner Family Collection. They show Redon exploring a wide range of drawing and print techniques before settling on lithography. In each medium, he labored over the surfaces to create shades of black—and, in the process, often to rub or wash them away.

Redon completed several versions of The Temptation of Saint Anthony, with text from Gustave Flaubert. However, he sought in printing a dream world that even the novel cannot evoke. In his last years, as success allowed him freedom to experiment further and to try more costly media, he creates his more famous pastels. Even in color, though, he smudges his still lifes and blends scenes from romance with clouds or color and shadow. In work like this, one never forgets the limits of appearances.

One should not overlook his reticence, even when he faces his nightmares. One expects something a good deal scarier, but he makes his dark angels bright, shy, and sympathetic. Even when the devil holds out the seven deadly sins, their black smudges do not seem all that tempting or threatening, and the most sinister of spiders seems almost to smile. Where a twentieth-century artist would make his subjects confront the viewer and tumble into the space of a gallery, Redon tends to set them apart, within the space of the work. Some retreat behind bars or within a dark architecture. As with Oscar Bluemner, another sad visionary who began as an architect, one can sense his early aspirations after all.

His reticence links him again to the academic instincts, especially when it comes to his relatively infrequent women. They have even ghostlier forms, and they rarely take much trouble to tempt him. Even naked, his men appear as lost souls, his women mostly chained as victims. Do not dismiss him for that, however. Think of him as enunciating the Victorian unconscious better than a realist ever could. He stands despite himself as the architect of that imagination, with the Modernism he influenced about to raze it to the ground.

Traces and indiscretions

The word discrete has a double meaning—as separate and distinct, like the pages of a book, or as observing the proprieties. One should never forget how Redon disturbs the borders between text and image, image and shadow, or a sequence of images themselves. One should not forget either how shocking his discovery of the unconscious is to this day.

I noted how readily one can dismiss art like this as small. However, Redon imposes his own vision, from the sheer size of his prints to their arrangement. He liked that one could browse or turn lithographs without regard to the sequence of Flaubert's text. In effect, he articulates the paradoxes of an artist's book today. The rush and intensity of Flaubert's demons could stand for an emerging artist's indiscretions now.

One could argue that the artists in "Dialogue" are trying to appropriate the techniques of mass reproduction for the values associated with the unique art object. One could argue that their felt collaboration can never match that of the heady days of modernist art movements. One could argue, too, that art institutions reach a wider public than a limited edition. The modern museum grew in order to provide the greatest access to the most costly works. Perhaps mass reproduction still collides with the aura of the work of art. Nonetheless, the market has absorbed each artistic rebellion, and the star system keeps demanding higher prices and more celebrities.

Perhaps a medium alone cannot determine what makes a work progressive or alive. Perhaps no one can say where media will lead, and perhaps media always respond to and add their own momentum to a changing art. Yet the very multiplicity of the artist's book should demand attention, and so should the art scene's reluctance to accept it. Painting was dead, one heard a little while ago, and now some painters move fluidly between canvas and the computer. Photography entered the artistic mainstream at last in the 1980s and 1990s, because two kinds of appropriation—the print and Postmodernism—found their aims starting to converge. Maybe now, in the digital age, the handmade work will also find a renewed space.

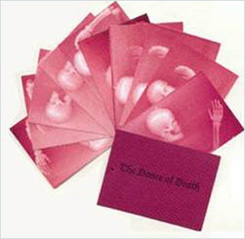

I began by pondering, with puzzlement as well as delight, exactly who gets to turn those gorgeous pages. That question helps to explain those recurring themes of transience, the physical body, and of art as a dangerous exposure. One senses it immediately in Sylvie Heyart's title, En Cet Instant Fragile, as well as her human subjects. It colors Schaer's decaying leaves and the grainy, distended eyes surrounding them on three walls. It colors Rosenberg's flip books, of skeletons ready to execute a Dance of Death. It colors Gilman's images, somewhere between abstraction and Surrealism, "against the evil eye."

A verse quoted by Christiane Vielle could stand for the rest, and it is not an entirely discouraging text for a show of art: Je ne suis / Que / Cette Main—"I am only this hand." The stubborn tension in an artist's book between art and text suggests the fragile nature of both. It also suggests the artist's heartfelt attachment to each. No wonder, for the moment, art is willing to play by the book.

"New York/Paris Dialogue Paris/New York" ran at the Abrons Arts Center, Henry Street Settlement, through December 17, 2005, at the Center for Book Arts through December 3, and at Long Island University through November 11. The panel, one of several presentations during the exhibition's run, took place at Abrons on November 4. "Beyond the Visible: The Art of Odilon Redon" ran through January 23, 2006, at The Museum of Modern Art. Portions of this article have appeared in Artists Books Reviews (Winter 2006).