Parroting Modernism

John Haberin New York City

Birds of a Feather: Joseph Cornell and Juan Gris

Martí Cormand and Sherrie Levine

On ne truquera plus les objets d'art: the work of art can no longer be faked. With Postmodernism, the thought had become something of a cliché, to be dismissed as quickly as possible. How, though, did it read at the very birth of Modernism, in 1914?

Juan Gris must have been delighted to stumble on just that headline in the morning news, alongside warnings of imminent financial collapse. He must also have taken it as a challenge. He had experience in fakery, whether the older art of illusion—or, with Cubism, the art of undoing illusion with its mind games and found materials. With Man at a Café, that page from a newspaper became one of those materials.  It became material, too, for Joseph Cornell, and the Met brings their trickery together as "Birds of a Feather." Closer to the present, Martí Cormand revisits the postmodern moment in the work of Sherrie Levine after Walker Evans.

It became material, too, for Joseph Cornell, and the Met brings their trickery together as "Birds of a Feather." Closer to the present, Martí Cormand revisits the postmodern moment in the work of Sherrie Levine after Walker Evans.

Fooling with art

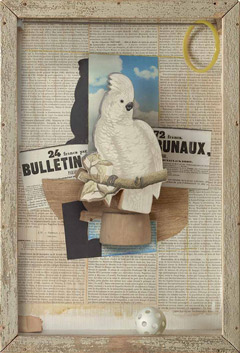

Joseph Cornell must have taken the headline as a challenge, too, but also the painter and the painting. He encountered it at a legendary midtown gallery, Sidney Janis, in the fall of 1953, and his admiration for Juan Gris only deepened after a MoMA retrospective in 1958. Together, they spurred twenty-one assemblages—all but three, like so much of Cornell's work, in the form of a modest wood box. Now the Met rounds up twelve of them from public and private collections. Behind their glass fronts, the café has become an aviary and the man its prized cockatoo. The work itself has become a transcontinental journey, and the morning news has faded into night.

The show marks the promised gift of the painting. Where Cornell pays tribute to Gris, the Met pays tribute to the donor, Leonard A. Lauder with the first of several "dossier exhibitions," each based on a work from his collection. And where the Met has catered to donors far too often at the expense of its finances, with museum expansions and the Koch fountains out front, Lauder may have earned it. He displayed his collection as a compact introduction to Cubism in 2015. The museum has already put on admirable "focus exhibitions" from its collection, in its galleries for European painting, but here its ambitions grow at that. Twelve of eighteen is not bad, especially when the location of at least one of the rest is unknown.

It can also boast of the painting, which threatens to outshine Cornell. Truquer can mean to take advantage in the sense of stacking the deck, and Gris knew, too, how art can stack the deck in its favor. Here a fairly large painting allows him to take advantage several times over. Where Pablo Picasso introduced fake wood grain with the carpenter's trick of a comb, Gris adds competing grains on two scales of fineness. He also adds multiple shapes and shadows, with paint itself as collage—to the point that one can hardly locate the man. There is his hand holding the paper, but is that his hat, his hair, his face, or his absence behind it? Is that silhouette on the wall his shadow or a waiter?

The Met can boast, too, of connecting Cornell to Cubism. He can come across as the belated heir of Kurt Schwitters and Surrealism in America—or as a folk artist and outsider obsessive enough to have turned out so much in this one series alone. Where others in 1953 celebrated the triumph of American painting at the Cedar Tavern, he at age fifty was on Utopia Parkway in working-class Queens. Yet he was sophisticated enough to have kept up with shows like those of Gris, and he knew Marcel Duchamp at first hand. His taste in art books appears in a display case, including one on Gris and a classic survey of Cubism. He browsed Manhattan bookstores for the texts and illustrations in his assemblage, and he was capable of puns in French.

He can pun on his own role as an artist with the great white-breasted cockatoo. The bird never appears in Gris, but Cornell can parrot him nonetheless. He borrows the painting's palette of faded newsprint, blue, orange, and yellow. In place of newspapers, he often has book pages in French or in one instance Spanish, in homage to the Spanish painter who worked in Paris—both within the box and on the back, along with the artist's signature. An ad for Apollinaris mineral water stands in for Guillaume Apollinaire, the poet and defender of Cubism, and the logo of Hôtel d'Etoile, or Star Hotel, for Cornell's absent hero and star. Silhouettes and shadows multiply as well.

Their variation alone sets works apart, with an obvious heir in the 1970s in Bob Smith. One box stands nearly empty but for the bird on a shelf and its outline in black paper seemingly fallen to the floor. Its toys, like a ball or chain rolling along a metal track, imply a birdcage. Still, whether a thick wood cutout or a clipping from a nineteenth-century naturalist, it stands triumphant over all. The names of European hotels proliferate, too, as if to deny the bird's or the artist's confinement. Cornell never crossed the Atlantic, but art could take him anywhere.

If he meets Gris on his journeys, it will be somewhere between day and night. Where Picasso's Cubism leans to neutral tones and Georges Braque to warmer ones, Gris captures the raking light of a café at night. The man nurses a foamy beer even as he reads Le Matin, or "morning." For Cornell, that paper has become Le Soir, or "evening," when Hôtel d'Etoile can rest literally beneath the stars. Yet Gris can also juxtapose sky blue with a more regal shade, while Cornell can paste pictures of the daytime sky, with the bird's crest echoing in the shape of clouds. Perhaps he took the headline to mean that one can no longer fool works of art, but he took that as a challenge, too.

After the copy

How long before an act of rebellion becomes a settled history? For Modernism in the 1980s, many believed, the time had come. Its very triumph, the story goes, had rendered it at best irrelevant and at worst a lie. Maybe, like many a revolution, it had rested on a lie all along. For Sherrie Levine in 1981, it was long since time to call it on its lies. With her photographs after Walker Evans, she sought to dismantle its claims to authenticity and progressive politics, so that she could reclaim them as a woman's own.

Still, the worm turns, and could it have turned against Postmodernism? "American Photographs," at MoMA in 1938, contained work by Evans for the Farm Security Administration, and a different selection appeared in book form soon after. Levine simply photographed twenty-two of its images and displayed the prints in Soho.  Now Martí Cormand copies Levine in her entirety. He did not quite wait another forty-three years like Levine, but the pace of change is faster these days. Is he piercing Postmodernism's myths, or is he, too, claiming the past for himself?

Now Martí Cormand copies Levine in her entirety. He did not quite wait another forty-three years like Levine, but the pace of change is faster these days. Is he piercing Postmodernism's myths, or is he, too, claiming the past for himself?

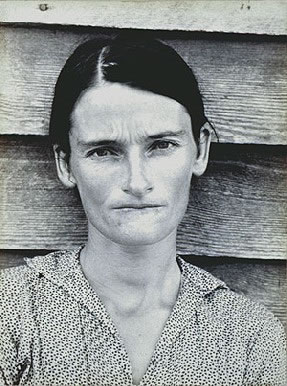

His small drawings sure look familiar, much as Levine, Cindy Sherman, and the "Pictures generation" traded on familiarity. They have the iconicity of the Dust Bowl, wood-frame churches, and a struggling family of five. And there is no mistaking solo portraits of the tenant farmer and his wife. The drawings could almost be photos, but that is the nature of a copy, and it gives new meaning to photorealism. They could also be directly after Evans, rather than, as the show has it, "after Levine, Evans"—but then how would one know? Score one more point for Evans or for Postmodernism, as you see fit.

Cormand is good at scoring points, from his grasp of technique to his grasp of history. His pencil has the spare precision of patterned dresses, the cross on a wooden church, or the raised collarbones on a tenant farmer's wife. It also has the softness and smudges to place them in a more comforting realm of memory. His subjects had their comforts, too, even in poverty, like the pictures on a wall or the portable clock on the mantel. Originally from Spain (assuming that one can talk here with a straight face about originality), Cormand is at home these days in Brooklyn, but these people were at home, too. Their churches stand empty, because Evans testifies to ordinary circumstances and not Sunday sermons.

He calls the show "Formalizing Their Concept." That could echo Modernism's demand for formalism, the conceptual art that rebelled against it, or postmodern jargon in discussing both. The gallery cites Lucy Lippard, who identified conceptual art with "dematerialization" in 1967. It then speaks of Cormand as rematerializing the work after Levine. The word evokes late Modernism's insistence on the art object, but then it places the original at a second or third remove. Besides, conceptual art often has a material element, especially today.

Levine, to me, has not held up half as well as many a contemporary, with a gratingly literal politics and strategy. At the same time, Evans holds up well indeed, with the idealism of the New Deal, an unsentimental eye, and even anticipations of Postmodernism in his postcards and penny pictures. His depth of focus hones in on the Depression with a frankness that could put even Cormand's fine graphite to shame. Call him a dead white male if you like, but the Farm Security Administration employed Gordon Parks, the African American photographer, too. Still, Cormand takes the risk of bringing the dead alive. Copy me on the next turn.

"Birds of a Feather" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through April 15, 2018, Martí Cormand at Josée Bienvenu through March 3. Levine ran in 1981 at Metro Pictures.