The Point of Art

John Haberin New York City

Paul Signac

Helen Frankenthaler: The Lighthouse

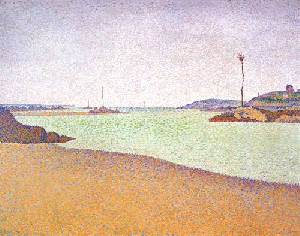

Paul Signac dreamed of a science of color, but he had little patience for experiment. All his life, from his socialist youth on, he wanted answers. Naturally, he found them, too—in middle-class interiors and trendy seaside resorts. In the invention of the modern, he can seem a minor setback along the way.

Or am I wrong? The Met makes the case for an artist very much aware of my objections. It suggests an alternative track to Modernism. Indeed, a new series by Helen Frankenthaler returns to Signac's seaside vistas and intensity of color.

Modernism: the mummy

One can see why I have put off writing this for days, just as I put off seeing the show until its last weekend. Signac takes up Georges Seurat and his painstaking analysis of primary colors, but he leaves daubs of whatever paint he chooses. He reduces Seurat's summer heat to light, seaside breezes. Misunderstanding a revolution, he founds a school.

Without Post-Impressionism, of course, Modernism is plain unthinkable. In Vincent van Gogh's heightened brushstrokes and pen strokes and in the palpable weave of canvas for Paul Gauguin, one already sees art's reflection on itself and its materials. In their strange colors, van Gogh's all-too-violent emotions, his Cypresses, and Gauguin's search for the primitive, one sees how both art and nature came to mean more than a mirror image. With his later work or Monet in Venice, Claude Monet approaches abstraction. Above all, Paul Cézanne feels his way around each composition and the representation of space as if making them up from scratch every time.

Seurat may look backward by comparison. His Neo-Impressionism, as the name implies, points to the preceding generation, although it resonated with a champion of the avant-garde like Félix Fénéon. Like Impressionism, he still puts color at the service of sight. While Pierre Bonnard and others escape to distant or private worlds, Seurat sticks to the urban middle-class at leisure. He codifies the rules, some might say, for an old ball game. In fact, however, he takes a decisive step.

Like Cézanne, he anatomizes space, and he finds that its structure belongs entirely to art. Compared even to Cézanne, perspective goes right out the window, and a strict grid fills the pane. Within that grid, human beings take their place as one more object among others. They litter the scene almost evenly, without a hint of emotional contact, and bare-armed men relax not far from well-dressed women. So much for proper bourgeois pleasures.

Starting with the visible dots, a painting emphasizes its painstaking creation. One catches a creature in mid-leap, something Monet himself never dared, but it produces less an illusion than an unsettling stillness. He exposes the Impressionist moment in time, of pure seeing, as trickery, but a trickery peculiar to great art. A woman's bustle takes on the exaggerated curves of statuary. Light shines as if from within, and those dots of paint that define it also create a second, painted frame. Separation of the inside of the work from the world outside—or the inside of the museum from an esthetic creation, too—becomes impossible.

By contrast, Signac feels less timeless than mummified. Compared to the shock of raw primaries, from Seurat to Mark Rothko, his colors run to a dimmer palette. Painting after Cubism agonizes over pictorial space. Signac's landscapes, like those of much American Impressionism, just look flat. Followers of Clement Greenberg sneer at "decoration." Signac embraces it, with curves of carnival colors for their own sake. No wonder Henri Matisse quit Neo-Impressionism in record time, along with the Matisse family business.

Stepping outside

However, Signac knew perfectly well what he was doing. He would have derided my concern for depicted space as Romanticism, but he had hope for progress. In his retrospective, I began to see why. Sure, he never captures Seurat's warm light and coldly analytic vision, but he finds his own Modernism after all. He asks for modern art as visionary as science, as ideal as color for its own sake, and as down to earth as soil.

Seurat reflects on the illusion of space and of a moment in a time. Signac breaks with the tradition entirely. Seurat chooses themes, such as a suburban resort or a carnival, that take on the middle-class culture implicit in Monet's seascapes. Signac scorns the bourgeoisie. Seurat makes color into a science of light. Signac grants art and color a science to themselves. Seurat blurs the line between pictorial space and the frame, as if the viewer had no certain ground outside the work. Signac wants the artist firmly outside the scene, so that art can stand as an object in this world—and a rather special one at that.

One can spot his belief from the very start, before that excited encounter with Seurat. In the very first work on display, Signac turns the Impressionist point of view inside out. He paints the scene inside his studio, looking directly at the bright rectangle of an open window. One sees the edge of an easel at left and a man's legs at right—but almost nothing else, and certainly not a landscape. Instead, one looks directly into a blinding light. Only the long, brilliant stroke within a dark brown pants leg shows what color can do.

Signac shows his virtuosity, but he grounds it in the cramped environment of a working-class novel—or a struggling artist. He takes Impressionist light and color as his subject, but as elements within the painting. The human leg, like the easel's, could not conceivably belong to the artist at work on this canvas. Yet either leg could stand for the painter taking a break from the serious business of art. Somehow, he has walked out of his own painting. Signac asks art—and the viewer—to step outside for a fight.

He certainly walks out on the suburbs and cafés so dear to Impressionism. Influenced by Emile Zola's realism, he returns often in those years to the industrial and working-class outskirts of Paris. At around the same time, Eugène Atget was at work documenting those bare streets and shantytowns, Paris's "Zone." Both painter and photographer capture wide-open boulevards and bare walls too poor to support a more vibrant life. Yet both, too, transform their environment by the nostalgic aura of their art. They give Impressionism, photography, and modern art at once a social history and an esthetic declaration of independence.

Impressionism invites the viewer into the landscape, to share in its light and the artist's point of view. Signac wants the viewer, like himself, outside the painting and the landscape. He wants to examine both with a critical eye, as objects in their own right. Even more, he demands that one do the same. From scientific socialism to a science of art and color, Neo-Impressionism and Modernism lay almost at hand.

Ode on a Grecian urn

Seurat's all-too-brief career came as an explosion, but Signac had to gravitate right to it. Just as obviously, he and other Neo-Impressionists took what they wanted. Seurat showed how to treat color for its own sake. It took science, the precise observation of tones in close proximity.

Science offered vibrant color and truth to nature, whatever that was. And Signac's circle admired him for both. More important, he could now let go of what he hated in Impressionism—subjectivity, chance, and the passing moment. The group called its art Divisionism. One thinks of Zola, bringing to art the smallest units of biology, genes. One thinks of Marxism, with another kind of strict determinism, in units of money.

Science offered art not just a means of analysis, but a truth of its own. It brought not only firm, lasting principles, but also a chance to reach for the eternal. In La Grande Jatte, Seurat adds people to a quieter scene he had sketched from life. In this way, he can better define a grid for his cabinet of momentary forms. Signac pulls off the reverse. He empties his beaches of men and women, so that nothing transient can stand in the way of art.

The largest of Signac's paintings return indoors. He lets men and women back into art, not to relax and play, but to ignore each other over breakfast. A woman gets the silhouette of a Grecian urn, like Seurat's great lady, but not the commanding dignity. She echoes the modest pitcher on the table. People have more emotional closeness to furniture than to one another, but objects still have a shot at art.

That same pitcher casts multiple shadows, part of the myriad lines and curves breaking up the surface. Seurat asks for the perfect unity of mathematical perspective and surface order, with diagonals of pure tone and horizontals of art. Signac ditches the grid, so that a surface can have a life to itself. In perhaps his most daring painting, arbitrary pinwheels of color spring from the hand of a writer, who holds his hat and cane like a magician's props. Art and words alike spin their illusions, and the more one recognizes the trick, the more dazzling it gets. Not even Matisse anticipated anything that flat, decorative, and programmatic.

Seurat aspires in another way, too, to the mundane grandeur of a pitcher. He draws on a limited palette of decorative shades—typically pale blue, bright yellow, orange, and white rather than primaries. These colors do not combine to produce light, but to glow for their own sake. If the atmosphere feels flat, foreground objects shine with a color all their own. Light rakes over a hillside or bank of sand with a steady, somber glow. Painting aspires to ceramics.

Art's dot.com

The show did not teach me to love Paul Signac, but at least I can see why his contemporaries so appreciated his colors. I can see why the first Impressionist, Camille Pissarro, shifted his career one more time—in the process, drifting further apart from Paul Cézanne and Cézanne drawing. With each color, Signac announces a discovery. Seurat has a palette right from the start, the tools of science. Signac treats each color as a discovery, as the product of scientific observation.

Alas, his victory hardly lasted. Soon after the turn of the century, his output drops, and his art grows tamer than ever. He surrounds a whole painting with a single hue, like a Matisse on sedatives. The former socialist moves to pricier resorts. His watercolors forego dots for scraggly lines, like Sunday sketches of café society after all.

Still, I can at last see him as an alternative path to Modernism. Sure, Seurat or Cézanne leads to an art of daring and struggle, modernity's an anti-utopian side. Art as distinct as Cubism and Surrealism shared it. Pablo Picasso or Alberto Giacometti gives viewers no safe place to stand apart from a work. Even now, Jacques Derrida makes puns on the frame into an emblem of the future.

Signac could stand for another strain entirely, the strain of utopians from Alexander Rodchenko and Wassily Kandinsky to Piet Mondrian. Even a Kandinsky Composition refuses the distinction between fine art and decorative or functional media. In turn, these artists hoped for a revolution—in art, the individual, and society. But then, as Philip Ball shows in a wonderful recent book, a science of color may yet make sense, and it can illuminate the entire history of art.

Modern art and science go together in another way, too, for postmodern critics have torn into both. Utopias in art or science, as in nations, turn all too easily into nightmares. Science and the avant-garde, the argument continues, both hinge on individualism, a pretense of eternal truths, and bloated, exclusive institutions. Perhaps the road from Pointillism to dot coms is shorter than I think. The former still grows in market value, too.

Signac's real lesson, however, is that Modernism had many strains and many potentials. For every ideal of objectivity, it offered a contrasting ideal of complexity and criticism. Art had long hinged on the fiction of an untaught, naked eye. Signac demands a critical eye. Instead of the lens of a craftsman, he offers the lens of a scientist. Whatever I may think of his idealism, it is at least a defiantly modernist utopia.

To the lighthouse: a postscript

Painters still have the power to turn one's head around by freeing up color. Does Signac seem too pre-modern to me, just when he is setting the stage for a new century? Helen Frankenthaler heads back at once to Signac's sandbar and the thicker mist of J. M. W. Turner and Turner seascapes. In the process, she runs right through the vocabulary of abstraction. She also makes fields of color so vibrant that they seem on fire.

A lighthouse makes a good metaphor for Modernism's inquiry into light and space. For Virginia Woolf, in To the Lighthouse, it gave a point of reference for fragments of consciousness. Frankenthaler barely hints at its presence, but it anchors her best paintings in years.

In one, blocks of color represent buildings and landscape elements. They define a single horizontal and vertical, enforcing a simple grid onto a white background. In another, a softening of white and gray barely disrupts a saturated red field that covers the work's every inch.

In these and other ways, she plays methodically but instinctively on the possibilities. For once she never has to fuss over paint and composition. And that red is hard to forget.

"Signac: Master Neo-Impressionist" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through December 30, 2001, while the Lehman wing displayed Neo-Impresionist work from the Met's own collections. Eugène Atget's photographs of "The Zone" ran at Ubu gallery through January 5, 2002, and Helen Frankenthaler's "Lighthouse Series" at Knoedler through January 12.