Bringing It All Back Home

John Haberin New York City

Martha Rosler and Sarah Lucas

In 1965 Bob Dylan bid farewell to the protest movement, with "Bringing It All Back Home." Just two years later, Martha Rosler began House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, her farewell to painting in favor of photomontage and politically engaged art.

Speaking of political engagement, if you want to make an omelet, you have to break a few eggs. For Sarah Lucas at the New Museum, make that hundreds of them, on her way to a thousand. First, though, an older artist with women, walls, and food on her mind. It takes Rosler to bring those concerns back home.

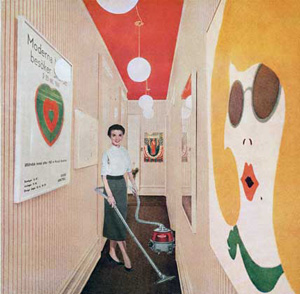

Like Dylan, she, too, could be alternately bitter and lyrical, from a Vietnamese mother with a bloodied child in her arms to an American mother and child on a bare mattress while the father zooms in with a toy airplane. Had her subtitle already become a handle for post-traumatic stress disorder in veterans?  She could also be relentless. The series resumed in 2003 for the second Iraq war and spookier tableaux, with young women caught up among duplicates like zombies—or just teens on the cell phone. In each case, the artist is bringing the war to the ideal home of architecture and fashion magazines, and she asks whether that ideal is making war on women as well. Like so many of us under George W. Bush and now Donald J. Trump, she is still an insufferable know-it-all. She is also far funnier and harder to dismiss, at the Jewish Museum in retrospective.

She could also be relentless. The series resumed in 2003 for the second Iraq war and spookier tableaux, with young women caught up among duplicates like zombies—or just teens on the cell phone. In each case, the artist is bringing the war to the ideal home of architecture and fashion magazines, and she asks whether that ideal is making war on women as well. Like so many of us under George W. Bush and now Donald J. Trump, she is still an insufferable know-it-all. She is also far funnier and harder to dismiss, at the Jewish Museum in retrospective.

"Irrespective" runs to just over sixty works, even counting each photo or photomontage in series as distinct, but it feels relentless all the same. As curated by Darsie Alexander and Elihu Rose, it confronts visitors with a woman at her makeup, selections from Body Beautiful: Beauty Knows No Pain—and that is just the entrance wall, barely six years past Rosler's 2012 Meta-Monumental Garage Sale at the Museum of Modern Art. She gained attention in late 1974 with The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, a large grid in black and white alternating photos and text. The first are blank and empty of life, even impoverished life, in favor of a shuttered bank front and empty liquor bottles. The second pile on the synonyms for drunk. Either way, this photojournalism is part of a continued struggle, not a "decisive moment."

No pain, no gain

She left a still more lasting impression the next year with Semiotics of the Kitchen. At least her heroine threatened to leave one, wielding knives like Julia Child gearing up for a marital confrontation or a street fight. Still, for her every system is halfway inadequate or out of control. Synonyms on the Bowery run to lush and wino, but also to lit up and happy. And the deadpan woman in her kitchen is Martha Rosler herself, not to mention hilarious. When she returns to the streets for her Greenpoint Project in 2011, with the photos and stories of nonwhite residents and aspiring artists or restaurant owners moving in, neither is the obvious villain in a class war.

Besides, these are her stories, too. She lives in Greenpoint, somehow long pulling off the commute to teach at Rutgers in New Jersey. A native New Yorker and graduate of Brooklyn College, she spent over a decade in Southern California beginning with grad school in 1974, but her themes and media were already falling into place. She photographed the Bowery at the time of East Village art. She may go gentler in the kitchen in real life, but she did cook and raise a child. She made a tapestry from his diapers, thankfully laundered. The lettering in ink then takes her back to sarcasm and politics. Her son, Josh Neufeld, must have inherited both on the way to becoming a sometime collaborator and alternative cartoonist.

The thresholds of the Bowery are also what current art jargon calls liminal spaces, or places of transition, like the thresholds of a dream. And Rosler has often returned to them, too, with photos of subways, airports, and Rites of Passage like bridges or highways around New York. She combines her obsessions with these and food for a series on airplane meals. All adopt saturated colors, drab compositions, and odd points of view to keep them strange and unappetizing. She anticipates as well a contemporary concern for liminal spaces, surveillance cameras. A huge eye in Body Beautiful already overlooks the bathroom.

Still, she wants others to pass through on their own transitions. Her largest installation and performance space centers on a banquet table, where anyone can take a seat. The Dinner Party, with its banquet for goddesses by Judy Chicago, is blessedly far away. Rosler has had her transitions between generations at that. She has exhibited among women in Pop Art, and the woman vacuuming in House Beautiful has much in common with "Better Homes" for Richard Hamilton before her. Yet she also anticipates images of women in the "Pictures Generation," like Laurie Simmons and Cindy Sherman in the 1980s, or further ahead in Lucas.

Yes, she can be hectoring, all the more so after Trump. She overlays his ranting with the names of the dead to show that black lives matter and tapes a toy soldier playing "God Bless America." At least in 1988, a work was still defending Ethel Rosenberg, and an image of Patricia Nixon in House Beautiful, like so much political art, has dated all too quickly. Still, there is more. A 2006 reading on authority, from Hannah Arendt, ends with hope that "the surest way to undermine it is laughter." One may not associate the author of The Origins of Totalitarianism, with laughter, but for Rosler "an artist in the twenty-first century" has little choice.

When Rosler reads from Vogue on video, one might stumble past just in time to catch her recite "the brass handles of a coffin." Soon enough, she reads about a wealthy man who "stood as if encased in plastic." Yet "he was a man who above all else loved women," and "he was cunt crazy." And then Rosler shifts to the ads. Scarier still, Vogue fully intends the piling on of contradictions and clichés. I leave it to you whether to laugh.

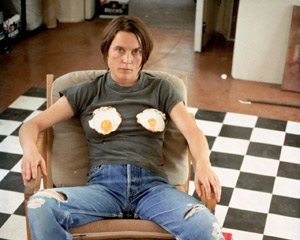

Break a few eggs

Sarah Lucas poses with fried eggs over a t-shirt in lieu of showing her breasts, their yellow for nipples. She has crushed many more for her retrospective without a thought of cooking. This is not about ruthlessness, pragmatism, or breakfast. It is about what goes into making art, being a woman, and having enough sex. She titled a commission for the Freud Museum in London Beyond the Pleasure Principle, and she could well have meant not a death wish, but a surfeit of pleasure. She asks aloud why the world, "given infinite possibilities," is so shabby and then proceeds to make it so—and you get to decide whether to join in her revulsion or delight.

Sarah Lucas began One Thousand Eggs: For Women just last year and declares it ongoing. She has flung its eggs against a museum wall, leaving long vertical streaks, a horizontal band of reddish crud just off the floor, and a pool of yellow below. It could be the ultimate drip painting, without apologies to Jackson Pollock—but then she is not in the habit of apologies. As two other t-shirts read, she is a Complete Arsehole, Selfish in Bed, and proud of it. She smokes often in her photographs (Marlboro, should you care) and lines a toilet with no end of cigarettes. Unlike Marcel Duchamp and his urinal, she cannot leave well enough alone.

Sarah Lucas began One Thousand Eggs: For Women just last year and declares it ongoing. She has flung its eggs against a museum wall, leaving long vertical streaks, a horizontal band of reddish crud just off the floor, and a pool of yellow below. It could be the ultimate drip painting, without apologies to Jackson Pollock—but then she is not in the habit of apologies. As two other t-shirts read, she is a Complete Arsehole, Selfish in Bed, and proud of it. She smokes often in her photographs (Marlboro, should you care) and lines a toilet with no end of cigarettes. Unlike Marcel Duchamp and his urinal, she cannot leave well enough alone.

She started showing in 1990 with maybe the most macho movement ever, Pollock and friends notwithstanding—but the Young British Artists have not aged well and are no longer young. Damien Hirst has become at best a nuisance, and I dare you to recall several others, despite an auction record for Jenny Saville. Art has a way of losing its shock value, but they depended on it. Lucas can seem a period piece, too. Like another woman in the group, Tracey Emin, she relies heavily on Britishisms and one-liners—and not just on t-shirts. Who associates cigarettes with rebellion anyway this long after James Dean?

She and Emin did, though, bring a much needed woman's point of view and a sense of humor. Titles like Laid in Japan have an unfortunate way of rubbing both in. So do her encounters with masculinity, like a penis and testicles of crushed beer cans or still another self-portrait eating a banana. The show takes its title, "Au Naturel," from a work—a mattress with a cucumber and oranges for male private parts, melons for breasts, and a bucket for I need not say. The curators, Massimiliano Gioni and Margot Norton, dwell on the pun on natural and in the nude, just in case you missed it, but you will have already moved on. Still, you will have moved on because the artist keeps insisting.

Lucas has only a few motifs, and they grow tired quickly only to gain in time from their variations on a theme. The photographs started almost as an accident, when she liked one of her by Gary Hume, her boyfriend at the time and another YBA. While many are black and white, a few in color reach the scale of wallpaper, like the ironic assertion of femininity and pretension of Divine. (The museum uses the fourth floor for big works, a dismembered car with more cigarettes included, before settling into chronology on the floors below.) She poses with little or no makeup in those t-shirts and torn jeans because what you see is what you get. Vox Pop Doris in the museum lobby, rough concrete in the shape of hip boots, could be a joke or a self-portrait, too.

So might her other recurrent motif, bare legs made of stuffed tights. They begin in a series as Bunny Gets Snookered—long, thin, and splayed awkwardly in found office chairs, with nods to contemporary life and Surrealism. They become a tad more realistic after 2000 before folding back on themselves in tight coils by the decade's end as NUDS and Penetralia. Lucas can never use stockings to simulate balls or distended breasts, like Senga Nengudi. Nor can she stuff them with basketballs like Martin Soto Climent in a show called "A Disagreeable Object." But then she has little patience for gender ambiguity or the seriously disagreeable.

She is way too sure of herself for either one. Her first solo show collaged photocopies from a British tabloid, with headlines like Fat, Forty, and Flabulous. Still in her twenties, she was at once proud of aging less than gracefully in public and disdainful of those who do. As a card-carrying YBA, she has little patience with her elders even now. Her increasingly evocative and compressed bodies have taken to plaster, cast bronze, photographs, and worse as Pepsi & Cocky, with nods along the way to nude photographs by Hans Bellmer and spiders by Louise Bourgeois. She will never have their ambiguity, their sensuality, their surprises, or their fears, but then Lucas will never tread on eggshells.

Martha Rosler ran at the Jewish Museum through March 3, 2019, Sarah Lucas at the New Museum through January 20. A related review looks at Rosler at MoMA in 2012.