Still Bleeding

John Haberin New York City

Faith Ringgold and Dewey Crumpler

After so many years, the flag was still bleeding. Will it never heal?

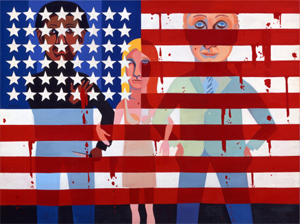

In 1997 Faith Ringgold returned to one of her best known and most potent images. The Flag Is Bleeding had come thirty years before as merely the eighteenth painting in a series, The American People, but it seemed to encompass them all. It held out the promise of the American dream, but a dream that could not staunch the blood. It drips from the heart of a black man, his face and his wound all but obscured by the blue field of stars. It drips from the stripes that match exactly its blood red.  Will the bloodshed ever end, and could a newer painting celebrate the survivors?

Will the bloodshed ever end, and could a newer painting celebrate the survivors?

Ringgold is still asking, and her answers keep growing more colorful, personal, and provocative. Her retrospective has three floors of the New Museum—all but the lobby gallery, with an installation by Daniel Lee. It makes the case for her as an American artist, as important and ever-changing as they come. She encompasses Modernism and folk tradition while recovering the faces and lives of black Americans past and present. She shows increasingly that African Americans can protest exclusion while entering the middle class and the museum, pain intact. But has anything really changed?

When Dewey Crumpler calls his show "Painting Is an Act of Spiritual Aggression," you better believe him. Now in his seventies, an artist with roots in Modernism is still moving "toward the spiritual in art." Faced with Wassily Kandinsky, who wrote a book with that title, he might find a kindred spirit—but not only with him. An African American, he also treats every work as a blow against the empire. Can he reconcile what may sound like utterly opposed views of painting? When this artist turns the other cheek, be prepared for the cheeky.

A pledge of allegiance

Ringgold's 1967 painting came at the height of the civil rights movement, in a decade of ideals, genuine progress, and serious bloodshed. The black man stands with a knife in one hand, narrow as a needle but life threatening all the same. Is the wound to his heart self-inflicted, or is he poised to strike back at those who would do him in? The painting cannot say, leaving open the terror and complexity of race in America. Is the nation's most potent symbols no more than a cover-up for terror and repression, just as the flag covers the man and two companions? Perhaps, but there are signs of hope.

The other two are white—a man in a suit and tie and, at center, a young blond woman. The three lock arms, obliging the men to crook their elbows in a display of solidarity and defiance. Even on his own, the black man raises his right hand to his heart to slow the bleeding. He might make it a little longer, and who knows what will have changed by then? Improbably, he pledges allegiance to the flag. Faith Ringgold need not bleach out its colors, like Jasper Johns before her, or ditch them for the colors of Pan-African unity, like David Hammons to come.

Still, bloodshed was not just a metaphor, and that was before the murders of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and Robert F. Kennedy. Soon after, Ringgold painted Die, inspired by the Newark riots a few years before. People run every which way, but there is no escape, and the drips continue. When MoMA reopened in 2019, after renovation and expansion, Die hung near Les Demoiselles d'Avignon by Pablo Picasso, as a reconsideration and a challenge. Its title could be sheer reporting or an imperative. Still, for Ringgold, her two paintings were a breakthrough, into human dignity and local color.

The American People is a dark series, with muted colors and faces packed close to the picture plane, even as Robert Colescott was lightening his approach to race and racism. So were her Early Works shortly before and the Black Light series just after. She described the latter as the application of color theory to black power although black light seems only right for dark and psychedelic times. Still, she had turned her back on a decent arts education, with abstract paintings to match. With the flag and the riots, though, her work brightens to take in a more plainly multiracial cast and the good old red, white, and blue, with plenty of red. Die also quotes Picasso's Guernica, so that a black artist can lay claim to art history.

Her aspirations are more obvious still thirty years later. Now the flag comes sixth in The American Collection, like proper fine art in a museum or private. At the same time, the series sticks firmly to the recovery of African Americans, famous and otherwise, and her goals go hand in hand. Back in 1967, a painting commemorated lost faces with a postage-stamp series. Now a painting has face after face of Bessie Smith, the blues great who died unjustly, in the style of Andy Warhol silkscreens. The later flag covers a black mother and two naked children, but they shine through.

Ringgold also frames them with pieced fabric, akin to Gee's Bend quilting and Tibetan thangkas. She began her "story quilts" in the 1980s, and they quickly take over the retrospective. Still, she is painting rather than weaving. The American Collection has its Aunt Jemimas and family gatherings, while other series embed famous black Americans in fields of decorative art and flowers. The back and forth between Western art and racial politics now takes place within a single work. That back and forth is the one constant in a rich and varied career.

Every night for dessert

Changes keep coming, with Ringgold a step ahead of anyone every step of the way. The curators, Massimiliano Gioni and Gary Carrion-Murayari with Madeline Weisburg, omit her early derivative work, which she has no interest in exhibiting. It also presents series close to intact, disturbing chronology a bit as needed, as is only right. As ever at the New Museum, I started at the top and worked my way down, which this once meant starting at the end. It had the advantage of a glorious opening, making me more aware of the richness and the back and forth. One can see it even in the early darkness.

Like the real thing, The American People are of all races, however dark, with witty and disturbing variations. An artist and his model are black and white, leaving it to you to decide which is which, but "his" is telling from a time that excluded women. Eyes have dark outlines and cheeks flat colors out of both African masks and European Symbolism or expressionism. If they also have the look of poster art, Ringgold applied herself to just that. She made posters for Angela Davis, the Black Panthers, and the People's Flag Show at Judson Church in 1970, but she moves easily from "free Angela" to "free yourself." She paints a mural for the women's prison on Riker's Island, now on its way to a permanent home at the Brooklyn Museum, and joins protests on behalf of diversity in New York's major museums.

If the documentation can wear you down, a poster's radial color fields, one to a word, break the darkness. Just as important, text becomes integral to work from that point on. The story quilts do indeed tell stories. Windows of the Wedding introduces unstretched fabric in 1974, and a Feminist Series embeds its narrative in floral patterns. Yet she draws back quickly from the abstract triangles of the first and the crowding of the second. Hand-lettered text adds a dimension, including the confessions of fictive alter egos, but it also helps her stay on message.

It may help, too, that she has less to prove. Now in her nineties, she has become an established artist. As a black woman, she can reconcile protest and decoration like Howardena Pindell or Myrlande Constant. Forays into sculpture rival the hacked wood of Beverly Buchanan. Its black assemblage picks up on the masks from her early paintings and the motif of mother and child. It can seem shocking, funny, or just lying around.

She engages the Harlem Renaissance and everyday life uptown. A family scene looks tense and the man worn down, but she can leave Tar Beach to fly over an ice cream factory. A logo promises ice cream "every night for dessert." She moves from Harlem to New Jersey, but she can never leave it altogether behind. "I will always remember when the stars fell down around me and lifted me up above the George Washington Bridge." At last, too, she can enter the museum on her terms.

After The American Collection comes The French Collection—and proof if any was needed of her knowledge of modern art. She enters the studio of Henri Matisse and the salon of Gertrude Stein. She takes Vincent van Gogh and his sunflowers to a quilting bee, positions Picasso as the woman in Luncheon on the Grass, and finally (yes) quotes Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. She goes dancing at the Louvre. Will the layered pleasures ever stop the bleeding? They can at least bring the humanity of bleeding home.

White robes and empty suits

For Dewey Crumpler, racism is just one more evil empire, and he is not going down without a fight. An opening collage morphs from a figure of uncertain race to Darth Vader himself, along with goodness knows what in bubble wrap. He knows that the good guys do not always wear white, not in this America, but he is not taking the power of evil as a given either. In one painting, tailors in black robes measure out a Klan uniform. In another, a black figure in red glasses and a white robe has the podium at MoMA while an audience of white robes makes it standing room only.  Behind the speaker, Die by Ringgold hangs alongside Pablo Picasso, much as at MoMA's reopening after the lockdown.

Behind the speaker, Die by Ringgold hangs alongside Pablo Picasso, much as at MoMA's reopening after the lockdown.

Still, do not start cheering too soon a display of racial unity. The scene could just as well be a protest, much as Ringgold joined museum protests against a near absence of black artists. Die is itself a painting of race riots. Does the packed audience represent a happy ending, joining black and white? It is hard to say, since one sees them only from behind, while the tailors, more accurately, are nothing but black robes, without a body. They give new meaning to empty suits.

Anything is possible in art, but also in science fiction, and Crumpler has moved more and more toward fantastic subjects and a cartoon style. It helps him keep his sense of humor and expand his cast to outer space. Paintings are inhabited by stars and space travelers, including nothing more than eyes. Maybe extraterrestrials will sweep racism away, and if not there may be "a hell of a good universe next door" as a last recourse. (To wrap up the quote from E. E Cummings, "let's go.") Either way, an artist's eyes are determined to look.

I hate to cheer the trend toward paintings as cartoons, with shallow crowd pleasers like Mr., now in Chelsea, or KAWS. Crumpler may be self-indulgent, but also self-aware, in a career that has ranged all over the map. A San Francisco artist, he might well be marginalized even if it had not. He has made collage with sneakers and photos of fighters, black and white, with a nod to Pop Art. Speaking of Wassily Kandinsky, he has worked in abstract art as well. Even there, though, one might read the grids as the façade of public housing.

Crumpler found an early supporter in Elizabeth Catlett, with a similar mix of sources from African art to black power. She also introduced him to Mexican muralists, and he caught examples of their work in Mexico and the Bay Area itself. Nor are Picasso and Ringgold his only quotations from modern museums. The twin tailors labor beneath a painting by Philip Guston, who might have supplied a template for their Klan uniforms in Guston's Klansmen. Elsewhere one can share in a giddy afternoon of kite flying, but with urinals in place of kites. Just in case you missed the allusion to Marcel Duchamp, who turned a urinal into art or anti-art, another painting takes you back to MoMA, where Duchamp's stands between two water coolers.

They are free-standing, inviting you for a drink or a pee. Have I been sucked in by the promise of cheap refreshment, including the satisfactions of recognizing famous art? (Duchamp's Fountain shares the room with paintings by Piet Mondrian and Henri Matisse.) Maybe, but they have a discomforting side as well. The kite flyer is another empty robe, and the urinals lift him off the ground, denying firm footing. Dark figures in white robes approach a border at sundown, where a sign promises Everything You Want! Everything You Need!—but not, I fear, for them.

Faith Ringgold ran at the New Museum through June 5, 2022, Dewey Crumpler at Derek Eller through April 23, and Mr. at Lehmann Maupin through April 24.