Exile on Main Street

John Haberin New York City

Shirin Neshat

Was all the world ever a stage? In early video art, it looked more like an awkward, thought-provoking mix of sculpture and performance art. Now, with digital technology everywhere and video art as marketable as painting, comes the home movie.

So where does that leave a struggling video artist—or a viewer? Imagine Hollywood movies or reality TV, only now compressed, as if to revel in each passing moment of personal experience. I can only marvel that some remarkable things get done. Take the latest from Shirin Neshat.

Divided sympathy

Neshat, born in Iran, makes videos about women in far-off nations, under a religion that, at least until a terrible day in September 2001, few Americans knew. It sounds like a way to get attention anywhere but in New York, where art of the Arab lands is only slowly gaining attention. Yet two years ago, she put all that at the center of the art world. Not long after her eerie Turbulent, her Rapture dominated the galleries, a show of "Greater New York," and a Whitney Biennial. It takes center stage in the latest essay collection from a distinguished critic of late-modern painting.

She did it the old-fashioned way. She took as her theme not just her subjects but a very modern idea, distance itself. And she did it with a message at the heart of Modernism: nothing is only one thing. At least in Rapture, part of a black-and-white trilogy on two screens, it is exactly two.

One screen holds a loose cluster of men. They circle about in something between free play and an uncontrollable riot. They act very much as individuals, wildly alone and never touching, but they lose themselves in a community they cannot begin to understand. On the other screen, women stand erect, facing rigidly forward.

The men have their arms free and wear white, loose-fitting shirts. They occupy a fort, a signifier for culture at its best and worst, both concerted action and the mindlessness of war. The women seem weighed down by the traditional black garb covering them from head to toe. Their tight, airless grouping denies them a sense of space or place. If the sand beneath her feet stands for a woman's traditional association with nature, here men assign her nature, and it makes for a harsh mistress.

The women's frontal stares, though, give them a power, complexity, and even autonomy denied to the men. These women engage a viewer and demand justice. By meeting one's eyes, they create empathy, whereas one looks at the men from the safe distance of a judge. At the same time, they stare one down, an accusation surely directed at the traditional male gaze. The viewer becomes, in effect, an extension of the riot in the other screen. One has as much responsibility—and as little comprehension.

Then, too, the robes and stares put the viewer at a distance from both screens. As part of the fundamentalist revival, some women adopted the plain dress in rebellion against a Western form of oppression—commercial fashion. To confuse matters further, if one ultimately can claim no real intimacy with either the men or women on screen, neither can the artist. As an American, she stands in empathy, in judgment, and in exile. When, at the end of the video, a woman frees herself to dance, one shares in the triumph, but not without a hint of guilt and confusion. As in art as far back as Edouard Manet and his mirrored A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, one has no comfortable place to stand, whether in or outside the work, with or apart from the female display.

Grand opera and music video

Now fast forward, for time is growing short. These days, I have a lot of galleries to cover before I head home for TV. Neshat has more star power than ever, enough to help promote a retrospective of a much older Iranian artist, Ardeshir Mohassess. Passage, of June 2001, has music by Philip Glass and the cover of Art in America. But look who is watching.

Three newer videos of hers each take a single screen, and production values have skyrocketed, just when artists such as Jon Routson and Christian Jankowski delight in turning even Hollywood values into amateur hour and Barbad Golshiri brings video to Iran. Besides music from the composer of Einstein on the Beach and Satyagraha, I mean big screens in living color. As in grand opera and the movies, or Matthew Barney in video that quotes both, one sits back in a kind of awe. One had better.

Possessed demands it by a pronounced didacticism. A woman moves through the crowd while refusing to recognize it, forcing headway and raving. The madwoman in the attic has come to the village square. Pulse demands it, too, but in another way—with the provocative sexuality of remote cultures, of the West's proverbial other, and of film noir. A return to black and white, it pulls back in a single, long take right out of Orson Welles. A woman sheds her black robe, as if once and for all.

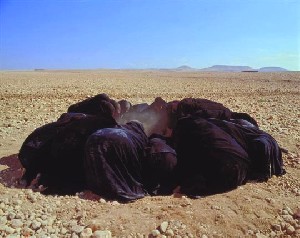

Passage, the most overblown of the three, is also my favorite. This one indulges in high seriousness and elusive imagery. A train of men carries a body across a desert plain, toward a throbbing, black, circular mass. The black shape dissolves into a circle of women, who create a funeral pyre that grows to consume the line of figures. Glass's score builds in intensity to a final sustained, raised note. Like the trilogy's themes of madness, death, sex, and classy costumes, it marks a curious throwback to grand opera.

The three videos maintain Neshat's obsessive oppositions. She sets women apart, like Newsha Tavakolian in Tehran, but the shared ritual leaves female artist and male viewer equally in exile. Neshat returns to the isolation, political and spiritual, of women in the Islamic world or, often, Islamic art. The packed, dark gallery and a split between image and sound track make the outdoors bitingly claustrophobic. Cultures have no access to one another beyond insanity and death, and yet they join in exhilaration and triumph. From scenes of madness and sex to ritual, Neshat could have called any of these three "Rapture."

Something has changed, however. The movies seem simpler, as if they had too little time to inquire into act of looking. The split screen seems to have come apart somehow, as if a hinge broke from the sheer force of hitting one over the head. In Rapture, a sense of release wins out in real time, with the woman's final dance. However, I came away remembering earlier moments, a montage more disarming and alarming, the frontal stare. In Neshat's later work, real time—the time of museum blockbusters and music video—wins out for good.

Video art and home movies

Video art's birth, like Pop Art and Minimalism, seemed to spelled an end to generations of formalism. Critics pointed to the new mix of pop culture and theater, as well as the unrelenting look at the constructions behind vision and feeling. Can video now sit safely in the past? Some of the best video art still plays with a viewer's engagement and a work's material reality. But then the continued engagement between Modernism and Postmodernism is what keeps them alive, too.

With Nam June Paik the TV set literally enters the picture. Gary Hill brings philosophies of perception alive by forcing viewers to wade through complex installations. Bill Viola creates his darkened rooms and formidable spectacle out of nineteenth-century magic acts, but they work by giving one nowhere to sit. Replacing narratives with cycles, they also leave one no handy way to wrap up their message and absorb it comfortably into one's passing existence.

I wonder if I am mistaken in seeing a change. Video after video has blown itself up to the size of gallery walls, while staying put on the wall after all. Not long ago, new media insisted on utter confusion between a medium and the physical means of creating it. Now the image takes over, and it confuses the viewer in a simpler way, by the enigma of imagery.

That may sound like a return to another strand in video's history—museum videos of the 1960s. Yet those insisted on a stark, choppy, even documentary image. From a bolder scale and color to new, digital tools for dismembering reality, the videos I am seeing now have learned more from Hollywood than from the avant-garde. They even tell stories, wrenching ones, about an old-fashioned hero, the artist. Imagine the overwrought, sentimental side of Hill or Viola, only with a greater sense of place and a bigger ego.

Neshat has gone in that direction, too, in her engagement with a fully imagined Islamic world. But video art almost everywhere unfolds as home movies made public. It uses narrative time, not chopped up as in the avant-garde, but compressed. Now each moment has a weight of its own. This is the rebirth of personal time.

What lies behind the rebirth? It could stand for careers in an inflated art world. It could stand for the success of MTV and of digital cameras and personal computers now so near at hand. Could it stand, too, for divided loyalties—with Postmodernism caught between critique and chaos? Like the Rolling Stones, Neshat lives as an exile on main street. She may need split screens again after all.

Shirin Neshat ran at Barbara Gladstone through June 29, 2001. A follow-up review encounters Neshat in 2005, more engaged with other worlds and other media than ever.