Indirection and Revolution

John Haberin New York City

Iran Modern and Hayv Kahraman

One may not bat an eye at finding calligraphy at Asia Society. Nothing else so bridges centuries of art from China to the Near East.

Nothing else, too, so bridges the four sections of "Iran Modern." The show looks back to before the 1979 revolution, for a different political climate and yet also a time when Modernism still ruled in the West. It also refuses a simple explanation of what made Iran modern. For that, you might need a greater feeling for what Iranians fear in the present. Hayv Kahraman knows the fate of women under western eyes and, in a religious state, fearsome repression. Could another revolution be coming, and can it have any more success? For now, even the most vivid of imagery accompanies only silence.

Under western eyes

The script has its own room, including classically trained calligraphers with texts from Persian poets and the Koran. It serves as a springboard to abstraction, much as it did for Mark Tobey in the 1950s in New York. It runs across political art, in the very texture of clothing, as sign at once of a loss of meaning and of a voice for the oppressed. Saqqakhaneh, the founding movement of the 1960s, turned to it for a specifically modern and specifically Iranian visual language. And much of the show's fascination comes in asking whether the artists found neither or both. Much, too, comes in asking what they lost when their visions came to an abrupt end, with the revolution.

Something else, though, departs from the official text. At least one artist, Reza Mafi, used calligraphy for what the Society calls "encoded political messages"—a theme, too, of forthcoming Asia Society triennials. Maybe you think of modern art as revelation, the dream of setting aside tradition for had never been seen before—or of setting aside illusion for what was before one's eyes all along. Maybe you think of the 1960s and 1970s in the West, between Pop Art and Minimalism, as plain as day. If one thing unites those same decades in Iran, it is how to flourish under prying eyes. Whether as politics on the street or as a world apart in an artist's dreams, it is an art of indirection.

Under western eyes, "Iran Modern" is bound to yield its secrets slowly. Few New Yorkers will recognize its artists, its texts, or its history—and, up to a point, the artists meant it that way. They saw an encounter with Western art and culture as long overdue, and they saw that encounter as a break with tradition. At a time when Abstract Expressionism was giving way to Pop Art, their imagery included mirrored soccer balls, Romain Gary, and Katherine Hepburn as the madwoman of Chaillot. And the creator of the first, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, is a woman. A folding sculpture out front, by Mohsen Vaziri-Moqaddam, has the charm of a gigantic Tinkertoy.

Yet they also meant Iran to meet the West on their nation's own terms, much like Wael Shawky in art today confronting the Crusades or centuries of Asian artists in hell. A key early figure, Charles Hossein Zenderoudi, prowled Tehran for imagery, equally at home in poor neighborhoods and the past. His pictographs include astrolabes and ancient talismans, in tribute at once to the golden age of Islamic science and to folk art. Farmarz Pilaram's ink and watercolors includes gilded castles barely a step away from abstraction. Another pioneer of Saqqakhaneh, Parviz Tanavoli, turns heavy locks and faucets into sculpture. Mark di Suvero or Melvin Edwards might have welded them, had they converted to Islam.

They could be signs of modernity or leftovers from another age. Tanavoli's ceramics and carpets of small stones would fit right into the Met's Islamic wing. So would Mafi's Persian tiling and relief script, after a fourteenth-century poet. One sees little of the present, even in political art. Houshang Pezeshknia's social realism makes a point all by itself, but his hard-hats never actually labor. So do Nicky Nodjoumi's blood-stained prisoners or Nahid Hagigat's women, but one never sees the torture or the torturers, and only clouds attest to surveillance.

Theirs is a heartfelt but oblique protest, like Asal Peirovi or, in the galleries, the parents of Sheida Soleimani, belonging fully to neither east nor west. Iran and Iranian art was modernizing, but slowly—the very impetus for a new movement in art. Imagery intrudes everywhere on abstraction. How could it not, in a culture where, like the South in art for William Faulkner, the past was never really past? Behjat Sadr's geometric abstraction incorporates aluminum and Levelor blinds, while Leyly Matine-Daftary's center on birds perched on utility poles. Yet they are never far away from Bahman Mohassess's warriors, raptors, and minotaurs.

Reading Iran

The curators, Fereshteh Daftari and Layla S. Diba, see these twenty years as a second Islamic golden age. The Shah had instituted land reform, to break up the power of an aristocracy. He was out to make the capital a "cosmopolitan destination," with funding for the arts—and with visits from such artists as Robert Wilson. It had its first biennial exhibition in 1958, the year before its first dedicated art gallery, and Zenderoudi kicked off the new art at its third biennial, in 1962. Karim Emami, a critic, dubbed it Saqqakhaneh the next year, after the word for public fountains. These structures paid tribute to Shi'ite martyrs denied water in pitched battle, but they stood mostly in bazaars. If one wanted an art of the people, as they were and as they could be, why not begin here?

Art had everything to fear all the same. The same government that granted female suffrage also created the secret police, SAVAK, and its torture chambers. It empowered a prime minister, but on its own terms. One could look to the West for models, but its armies and money were sustaining the deal after a British coup. Meanwhile religious leaders denounced the annual Shiraz Arts Festival as decadent and immoral. One could turn to their growing movement and its alliance with Marxist protests, but at one's own risk.

And so Iran did, and the result was revolution. "Iran Modern" includes a time line and documentation. Yet murderers and their victims do not come with labels, no more than for Newsha Tavakolian in Tehran today. In a photograph, massed women shrouded in black welcome the Ayatollah to power. One slips easily back to Hagigat's protests against a patriarchal society or Ghasem Hajizadeh's painting of women as accusers, in the colors of Pop Art. No wonder art had worked by indirection all along.

Once one spots the strategy, one sees it everywhere. Zenderoudi could be said to have started it, with his private mythology of poets, prophets, and kings—and Christopher Myers, for one picks up on just that. So could Tanavoli in sculpture, and who will break those heavy locks? The strategy runs through calligraphy's elegant stylization, including a composition that Faramarz Pilaram called Weeping. Siah Armajani, who left Iran in 1960, borrowed his cantilevered architecture from Le Corbusier, including a reading room named for Thomas Paine, but his largest work is an implicit plea for reconciliation, a bridge. Ahmad Aali's Self-Portrait amounts to a stove swallowing its own hot air.

Not that Modernism ever told a simple narrative of progress. Revelations came with a breakdown of certainty, whether in the unconscious for Surrealism or language for René Magritte. His paintings had their own rather nice handwriting at that. In retrospect, Modernism was itself facing a crisis by the 1960s as to whether it could still be modern. And that poses another problem for "Iran Modern": can this art really hold lessons for either modernity or the present?

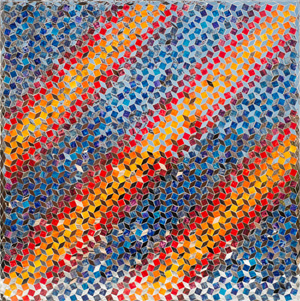

From the perspective of Modernism, Tehran was late to the game, and it shows. One sees echoes of Abstract Expressionism, but too often with far stiffer compositions and textures. Sadr applies a broader, more fluid brush to cardboard or metal, while Abolghassem Saidi's disks look back to Paris. References to desert landscapes in Sohrab Sepehri and Marcos Grigorian's cracked mud bring painting close to the earth before earthworks in America. Mostly, though, painting comes to life only when it abandons western flourishes for calligraphy. It allows Mohammad Ehsai's colors to recall Stuart Davis at his most rhythmic.

Houses and tombs

If "Iran Modern" is not exactly modern, neither is it contemporary. It cannot make political issues explicit, unlike Farideh Sakhaeifar or Barbad Golshiri today, and it cannot suggest their implications for the Mideast today and the borders of Israel. In 2009, several shows explored what a museum called "Iran Inside Out," with shows of art of the Arab lands still to come. Asia Society offers the prequel. Others might ask what Shirin Neshat or art of the present thinks of the pre-Internet age, now that it must find its own breaks with tradition and its own strategies of indirection. One will not find answers here.

Still, one will find an art worth seeing and script worth reading, perhaps especially when one does not know its language. The exhibition fills a gap that the Met's Islamic or modern wing cannot. Its roots in local bazaars and local myths suggest an alternative to contemporary art in Chelsea, where populism tends to mean empty spectacle with no real implications for politics, art, or people. Its pictographs and calligraphy dare one to figure out when it is extending older inscriptions or parodying them. In its different incarnations, that fold-out sculpture becomes downright site specific. One could stand a little more of that mix of transparency and ambiguity in New York today—and with Hayv Kahraman.

Kahraman passed through a dizzying array of nations and cultures, as if borne by the air, and so have the women in her art. How, then, do they carry so much weight? The very shape of a painting defies gravity. And then the women waft across, as if diving or reaching for the sky. Their translucent whiteness makes them that much more ethereal—and the thicker white of their faces, like masks or caked makeup, that much more inhuman. Human they are, though, and so is the space that they inhabit between their lives and New York.

Kahraman bases her paintings on the floor plans of houses in Baghdad, her birthplace. Their pieces fit together at all sorts of odd angles, without the firm order of a picture frame and horizon line, but with ample precedents. The diagonal joins could come right out of fifteenth-century Islamic art. Some have a floral pattern in the central court, perhaps the symbol of a fountain or rejuvenation. Not that these blueprints are blue, but the browns could arise from the ink in a Persian miniature, an Iraqi woman's skin tones, or the wood panel itself. If the last also makes explicit painting as material object, just as in geometric abstraction, so do the shaped panels—not unlike the Polish Villages series in wood for Frank Stella.

Here east does not so much meet west as confront it and move on, never sure what it has left behind and where it can go. Do the women themselves know? Their black hair and white faces borrow from Japanese art and perhaps netsuke. Yet their muscular turns belong to the Italian Renaissance, lending them dignity and agency, and some of their outlines nestle neatly within a room. They could be floating above the houses, remembering them, constructing them, or trapped within them. Other women (closer to Kahraman's earlier work) huddle more sullenly against lighter colors and vaguer geometries. One must also glimpse these few in a room apart, through grillwork out of decorative tradition in place of a door.

Has the artist found a home? She is not letting on, but she has come to rest in San Francisco, at least for now. Her art, though, seems quite at home in each of its points of origin, while acceding authority to none. An immigrant and a woman, Kahraman makes art about the outsider, after a decade of war has displaced entire populations. Yet that still leaves open questions of autonomy and responsibility. In a show called "Let the Guest Be the Master," a demand for hospitality may easily become more.

"Iran Modern" ran at Asia Society through January 5, 2014, Hayv Kahramanat at Jack Shainman through October 12, 2013. I continue elsewhere with more deaths, more protests, and Barbad Golshiri.