From Still Life to Abstraction

John Haberin New York City

Giorgio Morandi: The Magnani-Rocca Foundation

Piet Mondrian at the Guggenheim

It took Giorgio Morandi a long time to come into the light. He had to discover his subject, his palette, his brush, and his very detachment from what stood at only arm's reach. The discovery stands out from a private collection on view in Chelsea—and one of two fresh looks at the foundations of modern art.

Piet Mondrian can seem above it all, and perhaps he was. His abstract paintings make no concession to the viewer—not the enticement of color or hints of people, places, and things. You must value them for what they are. They are not even "in your face," like the sharp brushwork of Willem de Kooning or the nasty smiles of his women. In one of his earliest works,  though, he really is looking down from above, as earth and sea curve sharply away. Find your footing if you can.

though, he really is looking down from above, as earth and sea curve sharply away. Find your footing if you can.

Mondrian's planet leads off a focus exhibition of just thirteen works at the Guggenheim, drawn from the museum's collection. It is not an oval, no more than his Ocean four years later, in 1914, for it fits nearly and properly into a rectangle. He makes clear, though, that the painting reflects the curve of the earth itself. He is painting a dune in Zeeland, in his native country, where the ocean is never all that far away. He has come to the westernmost province of the Netherlands, also its least populous, but then who would dare populate his art? Patches of undistinguished color set off its elements. And then the warm blue of sea or sky looms up to fill out the canvas, much as Mondrian itself finishes off Ocean in monochrome.

Into the light

Giorgio Morandi was anything but precocious. At least one might not think so from his holdings in the Magnani-Rocca Foundation, and it should know. Luigi Magnani was a friend and early supporter. In place of the sheer lightness of his better-known still life, early work runs to dark, heavy tones, often close to black. Black may have drawn him to prints and pencil drawings as well. It can give Morandi's objects a history, too, of native instruments that can look both classic and quaint.

It may be his history as well, from an Italian painter in a modern scene increasingly centered on Paris, and he was fine with that, but he had to discover more. Born in 1890, he was adept from the very start, with the skills of an academic painter. That would explain the fondness for still life, darkness, weight, and those instruments out of the commedia dell'arte, much as for the Rococo and Jean Antoine Watteau. Yet it also had him thinking in the long term. If he was not precocious in the sense of child artist, he was in no hurry. He was in it for the long haul.

Early work also includes a landscape or two—and (surprise) a self-portrait. Already in his late twenties, he looks eternally young and slim, but still patient and secure. He is also testing the limits of time. Seated with a small, thin brush raised, he could be about to place the very next stroke, but he makes it hard to imagine his ever rising. An especially dark still life, encrusted with color, testifies to his admiration for Paul Cézanne, or so he thought, and its crust may reflect Impressionism. The curator, Alice Ensabella, sees just as much an older century and Jean-Siméon Chardin. He is still taking stock of his time.

Ensabella, a Morandi scholar, gives his early work the first of four large rooms, in a space usually reserved for the established and deceased. (Most recently it displayed a single large work by Richard Serra, curated by Hal Foster.) It can easily diminish smaller work, but here it allows a small retrospective. It comes seventeen years now after a full-scale Morandi retrospective at the Met. Rather than start over, let me ask you to read my longer review then. If he was slow becoming fully himself, he did live at home all his life.

What in due course changed him? Modern art, certainly, but also realizing his place in modern art. It was somewhat to one side, apart from Paris—but never all that interested in another Italian, Giorgio de Chirico, and Surrealism. As I wrote in the earlier review, he represents a third way to Modernism, neither Pablo Picasso nor Henri Matisse. Where Cubism had line and Fauvism had color, Morandi found weight and light. And he found them compatible.

What in due course changed him? Modern art, certainly, but also realizing his place in modern art. It was somewhat to one side, apart from Paris—but never all that interested in another Italian, Giorgio de Chirico, and Surrealism. As I wrote in the earlier review, he represents a third way to Modernism, neither Pablo Picasso nor Henri Matisse. Where Cubism had line and Fauvism had color, Morandi found weight and light. And he found them compatible.

That came with a serious departure. With a pencil or printer's tool, he had used dense fields of parallel strokes to model his subject with precision and polish. He moved largely to paler washes, in the color of wood or plaster, often stopping short of the object's edge. He could also stand household objects together, across the painting, each in front of or behind a wooden block. He was obliterating the distinction between the curve and the rectangle, foreground and background, home and studio, but also the thing itself and its space. The light belongs at once to the object, the painter, and the viewer's eye.

Above it all?

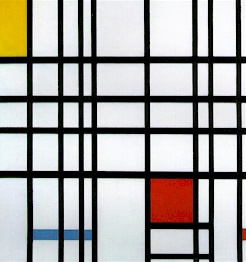

Piet Mondrian would never allow his subjects to divide a canvas, but he is still disrupting things. The Guggenheim has just two of his more famous compositions, from 1922 and 1939, their thick black lines containing and failing to contain upsetting fields of red, yellow, and blue. In one, the black stops just short of an edge and could well have begun elsewhere. Mondrian also turns squares to create diamonds, where the sense of cutting things off at the edge is that much more apparent. He may omit color altogether, leaving nothing to slow the collision of line and field, black and white, and yet everything is, pointedly, complete. It is, as he called his idea of an art movement, simply De Stijl.

It may not make compromises, but is it austere? Not when the colors and lines keep coming, and not when a diamond in black and white can hang high on the wall like the iconic monochrome of Kazimir Malevich in Soviet Russia. Not, too, when he could adapt to exile in New York with his late Broadway Boogie Woogie, now in the Hague. How did he get from Theosophy, an early interest, to jazz? How could he not? One could almost call his entire body of work a matter of theme and variations.

Is it consistently abstract? Not that either, although a modest success allowed him to quit work on still life. Still, he found his first mentor in an uncle, a still-life painter, and, like Georgia O'Keeffe, he drew both abstraction and single flowers. Like hers, they come alive from a point of view up close, which allowed him, he felt, to focus as ever on line and structure. A blue wash made some of them easier to sell, but color once again can seem incidental. Love them for themselves or as a step toward abstraction.

A selective show like this one can challenge what you thought you knew while summing up a career. But then a 1996 Mondrian retrospective at MoMA did both already. It came a long time ago now, not long after I began this long-running Web site. It changed my mind about him and allowed me also to explore whatever "theory" concerning Modernism was in the air. Allow me, then, not to begin over again, but to invite you to read on from the link just now. Here I focus on the Guggenheim in focus.

Just how, then, did Mondrian get to abstraction? The story does not run in straight lines, unless you count Mondrian's black vertical and horizontal lines of varying thickness. His Ocean seems to mark a transition from his earthscape in Zeeland. He constructs an ocean from a dense array of black crosses, like piers, but also like his later black. A still life centers on a flower pot on a crowded table—and then a painting nearly identical in size makes the pot its sole clearly recognizable shape. Yet he painted both the same year.

Was this a constant back and forth or a turning point? There is no denying the primacy of his later abstract art, although he also called it Neo-Plasticism, for it, too, was malleable and changing—not uniform, but in balance. Still, look again at his earth view to see what was already in place. Its curves refuse a familiar point of view, much as the Mercator perspective in an atlas must squash a globe onto the page. Mondrian's abstract art is a similar challenge to the single-point perspective since the Renaissance. It is his inhuman perspective on Modernism and New York.

Giorgio Morandi ran at David Zwirner through February 22, 2025, Piet Mondrian at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through April 20. Related reviews look more fully at Morandi in retrospective and Mondrian in retrospective.