Not Only an Eye

John Haberin New York City

Richard Serra: Forty Years

Everyone coming to Richard Serra's retrospective will have that special moment, when the light bulb comes on. Most will have the pleasure of moment after moment, when for a time everything seems so clear.

Maybe it will come at the entrance, once you have convinced oneself that the guard really means it: you can walk on Delineator, a long, thick metal sheet on the floor. One can, and it is safe, really. Nothing happens, except the experience of having entered an installation. One has to love moments like this. They equal the grandeur and composure of art in the textbooks.

And that, for better or worse, is precisely how the Museum of Modern Art presents Serra. Enjoy the experience, honest, even cherish it. But do not trust a second of it. Keep looking. Look up from that carpet of steel, against the ceiling. A second heavy plate hangs overhead, perpendicular to the first.

So clear

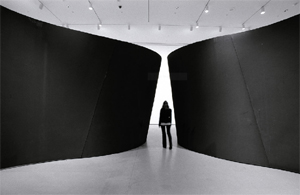

Maybe your moment will come in MoMA's galleries for contemporary art, on the second floor. There Serra has his largest work and the show's best segment. In the very first piece, rusted steel offers both a formidable wall and a choice of two enclosures. (And later Serra keeps getting larger.) One can take the measure of the reddish-brown surface. One can adjust to its arc and its mass. One can accept its tilt, its stability, and the amplitude of the space within.

And then one makes it outside again. Somehow it has another opening or two, around to the back. It has another space and another experience—almost but never quite the mirror of the first.

Or maybe that moment will come with the largest piece of all. This one, like some other recent work, consists of tilted, not quite parallel walls. One might expect to reach an interior after a few seconds of tension. One could then exhale deeply, again take its measure, and emerge where one began. If not, maybe one should keep going more or less straight and out the other side.

Instead, the space goes on and on. It broadens unpredictably, twists and turns, and at last lets one out, somewhere. Look around, and right there is a point of orientation of sorts—the gallery exit.

Those moments offer a kind of accommodation with a very controlling artist. Delineator stretches out less like a welcome mat than the approach to a throne. I have no trouble believing that Yoshio Taniguchi designed the oversized second-floor galleries, often so hostile to contemporary art, just for him. I have read so often about the relationship between Serra's work and Frank Gehry's that I am half afraid to visit the Guggenheim Balboa.

They also go with the whole idea of Minimalism, just as for Bill Bollinger. Sculpture like this is supposed to be clear—in shape, in mass, and in materials. It is supposed to define once and for all a relationship between the work, the viewer, and the space of the gallery. Working also with steel in Japan in the movement called Mono-ha, Lee Ufan even calls work Relatum. Yet again, for every such moment, there is more to come.

Manual transmission

Keep looking. Look at the photograph in the gallery handout, and that sculpture with two cavities to either sides makes more sense. At least it makes a different kind of sense. Band amounts metal curving back and forth like a plain, soft red ribbon. One could think of the museum cube as its gift box.

As for the longer Sequence, keep looking, and you will probably never get it. It relies on a pair of S-shaped walls. One follows the shape exactly. Twice, when the tip of one plate coils close to the center of another, it creates a roughly elliptical cavity. Near the entrance and exit, as well as near the center between the cavities, the walls approach a corridor. If you cannot quite picture it even now, you will just have to keep experiencing the work.

Art has sure come a long way from single-point perspective. If Claude Monet was "only an eye," as Paul Cézanne said, Serra calls for a whole array of senses. That helps to explain why people keep calling the show sensual. All those bulges and curves do not hurt either.

This kind of sea change in art did not happen overnight. Fleeting, sensual impressions go back at least as far as still life by J.-S. Chardin, but the assault on art as vision really kicked in with Modernism. Philosophers then were talking about "phenomenology," and Georges Braque described Cubism much the same way. "There is in nature a tactile space, I might even say a manual space. . . . This is the space that fascinated me so much." Of course, he and Pablo Picasso had seen Paul Cézanne.

The model hangs on in huge, trashy installations in Chelsea now. Maybe one can no longer touch very many of them. The gallery walls might come tumbling down, or the work's market value might. Maybe this art has given up trying to explore space, much less demarcate and define it. Maybe no one cares now what viewers know and think. Still, the sensual overload belongs in the same tradition.

Whenever the change came, however, Minimalism probably holds the patent. For someone like Dan Flavin, the artist and viewer each have a stake in creating the space around the art object. For Sol LeWitt, his own rules for execution cannot explain away a wall drawing. Serra just goes a bit further. When he bases mammoth sculpture on conic sections, he withholds even the rules.

The seminal artist

The artist came late to the game himself, with Serra's early work starting in 1966, but he dived right into its obsessive variations on a theme. In Verb List, he set himself an impressive task list—"to roll to crease to fold to store . . . to spell . . . to refer," but also "to discard" and "to hide." He displayed discarded rubber, as Belts on the wall or as fragments strewn everywhere on the floor. In his Splash Pieces, he ladled molten lead against the wall. It took "continuous repetition" to build a work. These pieces crowd out the observer and then some.

Soon enough they engage the viewer as if in hand-to-hand combat. In One Ton Prop (House of Cards), the four lead slabs supporting one another literally weigh a ton. In Equal (Corner Prop Piece), a pole pins another plate to the wall. Barnett Newman famously joked that Minimalists could not get it up. Serra apparently could, and one could only hope that it would not come crashing down. In fact, from the looks of things, the plate might have already sliced through the cylinder.

In the 1970s he discovered dark steel and began to use it, like Delineator, to map out a room. Instead of a balancing act, he adopts more secure foundations. The walls grow to twelve feet in height only in the 1990s, when they seem at last to bulge and almost sway. With the Torqued Ellipses of 1998, his sensuality finally comes into its own. Serra has learned to make work in which one can run or one can linger. He uses the bulges to entice, and he uses the open spaces between them to bring one closer or to create points of rest.

He also makes the paradox of measurement and immediate experience more explicit. As if to emphasize the dependence on sensation, the Modern starts in the middle of the story, with the early steel, before doubling back to the beginning. The mammoth curves pick up in the sculpture garden. The whole experience ends—or, if you prefer, begins—in the galleries for contemporary art.

Minimalism's phenomenology of the senses has its limits, too. As Hal Foster and others have argued, it posits an ideal observer, as abstract and impersonal as the work. Only the industrial materials supply a history—that and the need for a big, white museum box. As feminist criticism insists, too, the transcendental observer looks awfully like a man. Contrast Serra's prop pieces with the fragile, translucent molded tubes of Eva Hesse. His spoonfuls of molten lead give new meaning to the word seminal.

However, as much as anyone, male or female, Serra takes Minimalism personally. Robert Smithson considered entropy as a force of nature and a key to civilization. Serra settles for messy art objects, and his torn rubber looks downright soft and squishy. One could almost see a direct line to metal walls bulging like flesh or curving like a ribbon. He may have some narrow walls, like those of Bruce Nauman. Still, he never plays the class clown, taunting the girls in the hall.

Que Serra Serra

Even the challenge of his older work should take a male observer down a peg. He does not cede control of the space, and that helps restore both the artist and viewer to real time. The belts on the wall make me think of S&M. One can walk on his thick carpet, like floor tiles by Carl Andre, but one might also trip on its edge. One cannot kick it away, and if one could, one could not possibly put it back. Paired plates on ceiling and floor might work as an electrical capacitor, and I hate to think of the charge they could store.

At the same time, he has grown to accept the viewer's independence. And that, too, contributes to the sensuality of his art. Not all that long ago, Serra's work retained enough of its aggression that New York had to destroy his Tilted Arc. (Serra refused to relocate what he considered site-specific art.) Not any more—at least not at the Museum of Modern Art.

What has happened? In part, public controversy over art always seems trumped up in retrospect. Maybe workers downtown really demanded their favorite lunch spot back, or maybe politicians could not resist exploiting the voices of a few. Maybe the steel wall fought too hard for its public space, or maybe Federal Plaza will always chase people away. It looks as ugly and forbidding as ever, and right now it even has fencing around it for construction work. Serra deserves some credit for change, though, as well.

In part, he retreated to galleries and museums, like a politician building a base for his work. In part, museums needed a savior for sculpture, just as Frank Stella once offered a savior for painting. Serra let them affirm their own place at the center of the universe. In part, too, art has become closer to mass entertainment than someone like Serra or Frank Stella could ever accept. Now larger, more imposing art institutions can expect a larger, more receptive audience.

So many couples pose for pictures in the garden that I expected paperweight versions in the gift shop, like souvenirs of the Stature of Liberty. A sign for espresso appears to point to one sculpture, as if its four walls and three alleys set out the lines to the counter. And in part the work simply grew more relaxed, more welcoming, and more at ease with its slow unfolding. I rediscovered it to my own surprise, starting with his sculpture since 2000.

Serra wants appreciation, as Modernism's surviving old master, and MoMA sure presents him that way, too. It puts the prop pieces behind wood and glass barriers, like a design collection. ("Do you have chairs to go with that one-ton table?") It skips his mammoth piles of rubber or his steel bulkheads that drive one up against a gallery's walls. It even skips the versions of Torqued Ellipse at Dia:Beacon that most play hardball with entrapment and release. If the retrospective leaves out too much, however, there is enough of Serra's art to go around.

"Richard Serra Sculpture: Forty Years" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through September 10, 2007. Related reviews describe his recent gallery work and his early work and drawings.