The Game of Painting

John Haberin New York City

Helen Marten, Lily Wong, and Elizabeth Schwaiger

Now that painting is back and anything goes, where can it stop? Every so often one can still detect the guiding impulse of a painter amid the excess.

One might call Helen Marten a conceptual artist were there not so much on display, while Lily Wong does her best to put the magic back in magic realism. Elizabeth Schwaiger takes things further still, all but painting herself out of her own studio. If they all try a little too hard, let them. Such in today's overactive gallery scene is the game of painting.

The evidence is scattered

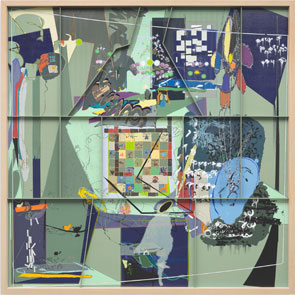

Art for Helen Marten is either the latest triumph of abstract painting or a game. Either way, a voice explains, it is "conquerable resistance," and how can you resist? Evidence of Theater weighs the evidence, with enough theater to confuse anyone. Her images hold out plenty of temptations, from cute little animals to breakfast cereal and an actual game of chess. Still, she has her devotion to painting. So which gives her work credibility, painting or the game?

Maybe abstraction was always a game. Postmodernism could point out the rules, in the spirit of seeing through them, while formalism could insist on them. And the game played out on a huge scale, in Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism. Marten herself has both floors of a gallery. The ground floor alone has space for a dozen large paintings, which morph upstairs into video. In place of a press release, your only guide is a personal essay, with due reference to Roland Barthes and other serious matters. "The fundamental structural agenda of evidence is scattered," she admits, "but it has rhythm and logic."

It also commands space, with (as the rules of Modernism go) art as object. Framed panels hang in larger white frames much like partitions, at all angles to the paintings and the walls. One rests on the lower white frame and the floor. Elements of sculpture and assemblage take them further into space. Most have a proper grid, as both an overlay of wood and a painted one. That still leaves space for savvy gestures, splashes of color, and cryptic symbols.

Still, is it only a game? The permutations suggest just playing around, and painted grids do look like chessboards. Physical chess sets appear, too, with abstract, unconventional pieces. They get along easily with a standpipe, a work desk laid out as a kitchen table, and much else. Marcel Duchamp, the ultimate modern chess player, would approve. And then there is the ultimate refusal of fine art's game, Kellogg's Corn Flakes. Was this Pop Art all along or just a more detached and devious game?

In prints within a panel, the cereal box and a corn flake rest in the hand of a smiling character with a striped suit, a white beard, and a preposterous handlebar mustache. Is he a product spokesperson, like Colonel Sanders, or a skeptic? Text in those prints gives the words of a psychologist, even as the person at hand keeps his mouth closed. "You can test reality," says the psychologist, where "you" could be either the consumer or the product developer. There is always the taste test. There is also, he insists triumphantly, that conquerable resistance.

He is not the only judge, quite apart from you. Once a figure in black robes takes his place, and once the painted image of a man leans forward, anxious or lost in thought. The more you look, the more others multiply, too, including (a title has it) "good judges." I do not believe they are the Bible's twelve judges of Israel. Is it hard evidence or theater? The Old Testament god has nothing on the demands of "theory."

For all that, painting rules if you let it. With such artists as Cecily Brown and Amy Sillman, the fluid space between abstraction and representation has become the norm. Quite apart from painting, Buckminster Fuller called one project The World Game, without a trace of cynicism. At stake in the game was the planet. What is at stake here is harder to say, and it may depend on whether you look at the big picture or up close for details—and on just how much Colonel Kellogg's gets on your nerves. For now, like Oscar Wilde, I can resist anything but temptation.

Not waving but drowning

Characters for Lily Wong may look strange at first, but only till you get to know them. And she knows them well. They have unnaturally blue or, more often, red skin, but not as blue streaked with yellow green as the ground beside them or as red as the stone wall that, just maybe, allows her to call this home. They are unnaturally present as well, but not as close or, again, as red as the rising or setting sun. Much the same colors streak the sky and their clothes. After a few minutes, they seem almost everyday.

There is a kind of magic in their magic realism, just as there is in holding a chambered nautilus between her hands and finding beside it her face. Or is it craft, much as with a tree whose roots flatten into paper,  run up to a window sill where a young man is seated, and emerges as a scroll for his focused attention? One can feel the magic anytime, in a man playing a flute or a landscape that opens onto an arbor tunneling into depth. Or is it all an accident? Rope that a woman uses to bind trees, of all things, ends up snagging someone else passing by. She turns aside anyway to look out at herself or you.

run up to a window sill where a young man is seated, and emerges as a scroll for his focused attention? One can feel the magic anytime, in a man playing a flute or a landscape that opens onto an arbor tunneling into depth. Or is it all an accident? Rope that a woman uses to bind trees, of all things, ends up snagging someone else passing by. She turns aside anyway to look out at herself or you.

One remembers most the color and the bodies, but not because Wong is obsessed with gender or sex. Two young men pose together, but not that way. This is her most intimate circle, with no obvious lovers or heroes. Most faces are scowling, and people may tense or bend like athletes in training, but only to fit into the twisting space that nature provides. Still, there is the strangeness of the everyday. Still, too, she can always rest her head in her hands, find a seat on a red staircase, tune out the many-colored stones, and consider what comes next.

Zoë Buckman has her unnatural tales, too, and she invests her women with more than enough magic. At least she hopes so, in the gallery's smaller space, for they are herself and her mother. They enter a busier narrative than Wong's, concerning family, race, and queer identity, and she insists on the details, with embroidered text. She has room for nature, but only because the images are a woman's work and their work. The flowers pick up on the patterns of traditional samplers, and the paintings incorporate old fabric as well along with drawing. I find them a little too explicit or not explicit enough, but it is an eclectic mix.

This gallery loves busy painting and good stories—as with Farley Aguilar, Max Frintrop, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Chris Hood, and Kathy Ruttenberg. Now Ruttenberg is back, with a fountain in the backyard sculpture garden, as Twilight in the Garden of Hope. As usual for her, nature and a woman compete for which will overrun or bear responsibility for the other. The result is a fractured fairy tale, as with her summer sculpture along Broadway in 2018. It is at once crazier and more focused than past work, too. By all means, get your hopes up.

Is it a coincidence that she called an earlier work in the garden Sunshine at Midnight? Here she revels in the middle ground. A woman floats on her back in the fountain, as water streams from above smack dab in her slightly contorted face. Everything along the fountain's edge, from mushrooms to a snake and what I take for ballet slippers, means well enough, unless they are poison, and so does a dog and a tree, bearing her image, presiding over all. You know the one about "not waving but drowning"? As the Band sang, "Ophelia, what have you done?"

The fierce urgency of now

Elizabeth Schwaiger paints and paints again an interior teeming with art and, just maybe, life. To be sure, she hardly has room left for people. Paintings cover the walls and spill out into the entirety of the space, where they compete with sculpture. Furniture itself seems a mere luxury—or an additional work of art. Still, she attests to the thoughts of a living artist—and the importance of art to her life. It has, as the show's title has it, the urgency of "Now & Now & Now."

Martin Luther King, Jr., spoke of "the fierce urgency of now," and Schwaiger knows its fierceness. She knows, too, that what is fierce is not always comforting. One can hear the repetition of her title pounding in her ear. If the title seems at all superfluous, everything for her is more than halfway out of control. Oversized sheets of paper spread out on the floor. They could be sketches toward painting, but they have pushed her finished work aside, and they appear as nearly blank sheets.

Their white stands out all the more because art has taken over in another way, too. Schwaiger overlays each painting with color, almost always a single color. She quotes "Diving into the Wreck," the poem by Adrienne Rich, and the monochrome ripples and obscures like ocean deeps. You might well be underwater, and the artist is in way over her head. So is the sole human presence that I could make out with certainty, a gaunt white silhouette. It could be her or yet another work of art.

Art appears, too, as a living tradition, that of the artist in her studio and of layered color. Henri Matisse and "The Red Studio" epitomize both, but examples are easy enough to find. The Met sets aside a room for the genre in its new galleries for European art. (It displays Kerry James Marshall, the contemporary black artist, and Schwaiger, still in her thirties, has a black-owned gallery, although she is white.) It can serve as a statement of identity or a celebration of art, and she may use a second color for highlights on sculpture. She has also used the studio, in an earlier painting, as a meeting place for many more.

Diving into the wreck sounds grim, but it has its attractions. Think of the appeal for divers of the Titanic. She also proclaims her love of childbirth and scuba diving, as inspirations for her art. Both recall her joys, her pain, and her fears. Mostly, though, she misses the fierce urgency. Like Rich, "she came for the wreck and not the story of the wreck." It is the age-old appeal, again quoting Rich, of "the thing itself." It sounds ever so Romantic (or Kantian), but it survives in late Modernism's plea for "art as object."

It also sounds ever so important, and Schwaiger also quotes Rainer Maria Rilke, the Austrian poet, in case you missed the point. She is not, though, pedantic. She really is painting art as the thing itself, to the point that its subjects within her paintings are left unseen. She may speak of the wreck of her art and perhaps her life, but her studio looks great. It has the ornate mirrors and transom windows of a European palace or museum. For all her preliminary smaller paintings, she needs the overflow of art and color.

Helen Marten ran at Greene Naftali through November 4, 2023. Lily Wong and Zoë Buckman ran at Lyles & King through October 14, Kathy Ruttenberg through September 23. Elizabeth Schwaiger ran at Nicola Vassell through February 24, 2024.