Where It Goes to Die

John Haberin New York City

Barbara Kruger, Henrike Naumann, and Lesia Khomenko

For far too long, the atrium of the Museum of Modern Art was a place where art went to die. Now, with Barbara Kruger, it is where democracy goes to die. And yet art and the atrium have never looked so alive.

She might have ripped her work right out of the headlines. "In the end lies prevail," screams text high on the wall. "In the end hope is lost." Kruger had to have planned her installation before House hearings on the Capitol insurrection had begun. Memories of false news are fresh, though, and so are fears that, since the Trump administration, they have become the norm. Besides, she has been saying as much in text art for forty years.

Kruger has always had her wild juxtapositions, between words, between words and images, or between words and the museum. She had an installation at the Hirschhorn in 2012, but this one is still making news—and putting responsibility for it in the hands of the viewer. It takes real work to decipher the tall, thick letters beneath one's feet, and then you can head upstairs and look down from the galleries to check your work. You get to decide whether she really means it. You get to decide, too, whether it has become an urgent reminder or a leftist cliché. Her found photos are gone, but text as itself an image remains.

If you think of Kruger as hectoring, elliptical to the point of confusing, or both, this show may yet win you over. Sometimes hitting you over the head can make a sensation. Besides, she has nothing on Henrike Naumann. Is this a new Cold War? It may seem so as Vladimir Putin loses his grip, Ukraine fights back, Joe Biden rallies Europe, and conservatives beg for less—or more. Still, if you are suspicious of slogans and labels, Naumann (no, not Bruce Nauman) directs her skepticism to old warriors and their mindset.

Which side is she on? One one thing for sure: she distrusts most of all those who claim the "radical center." At SculptureCenter, she turns her art against complacency, creature comforts, and consumerism in the West, as "Re-Education." And she sees them embodied in popular culture, art, and design. Meanwhile Lesia Khomenko sees war in Ukraine as more than a proxy between the powers that be.

A world of hurt

The atrium's dire warnings at MoMA may sound like nothing new, but then who cares for novelty when there are memories to preserve? Like others in the "Pictures generation," Barbara Kruger is that vital paradox—a critic of authenticity with an unmistakable style. She still works in sans serif, in black and white. You may remember it as layered on thick black or red stripes, but here it stands alone. You know that you have seen it elsewhere before, but where? It might be early Soviet art, Depression-era posters, or the dead hand of the censor, but it has become hers.

The show's very title reflects her obsessions with guilt, responsibility, and a terrible dichotomy: "Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You" (where what I have rendered as a strike-out is a sloppy green x. It is about you and me, much like the command crossing hands out of the creation in the Sistine Chapel: Admit nothing Blame everyone Be bitter.

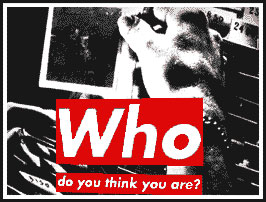

But then who are You—the gallery-goer, the American consumer, or an impostor? That, too, is tied up in a critique of power or authenticity, and Kruger is not one to admit much difference between the two. As a 1993 work has it, Who do you think you are? And, to rub it in back in 1981, you are not yourself. At MoMA you are looking through the looking glass, in curved perspective as if through a lens. The artist persists, but her subject keeps slipping away.

That slippage helps rescue the work from dogmatism—assuming that truth were not its own excuse. A Tragic Error faces off with A Trace of Grace. Still, Kruger is unrelenting, on a seeming endless march to the loss of hope. What seems so insightful on first discovery can soon become old. That text on the floor from George Orwell, about a picture of the future as a boot stamping on a human face, already belongs to dystopias past. They become the old sayings of a distant world.

A larger selection, new and old, suggests how she does it. Planned to accompany the installation before the pandemic, it came instead in mid-summer to her Chelsea gallery. Just for starters, surprises can arise from a litany itself, like her seemingly unending in the end. A multitiered crawl screen drives home her way with words. A litany of wars at MoMA has its surprises, too. Wars are never ending, but this means war.

Shows in MoMA's awful atrium have improved, a credit to the 2019 museum expansion. Six paintings by Susan Rothenberg found room to show off, and Adam Pendleton used every inch of its height for images of race in America. In the end, Kruger's installation is not just interactive but compassionate, about who is remembered and who is forgotten. Text art for her is not just a lecture, no more than for ironists like John Baldessari or contemporaries in anger like Glenn Ligon. This is about a world of hurt. This is about the moment when pride becomes contempt.

Cold warriors

Henrike Naumann holds out her share of comforts, but with strings attached. The partition leading in bears the exhibition title, in bone white and a gentle low relief. You may not even realize that the artifice is hers. Inside, she runs to found objects that further confuse the boundaries of art, design, and politics. A near circle of chairs offers a choice of places to rest, from pretend antiquities to a cheap modern office, with a child's rocker and a prop from American Psycho thrown in. Just do not try to sit in one or to start a conversation with your neighbors, for this is art. The Cold War is over, leaving a cold, cruel western world.

A wall unit has its charms and, by its scale alone, a taste of luxury, but a fish lies on the umbrella stand, and an oversized utensil looks suspiciously like a pitchfork. More hand lettering and Ikea curtains pretend to celebrate the Radical Centrist, while a literal iron curtain descends across the balustrade leading downstairs to the basement tunnels. A small back room becomes a "man cave," with a cheerful pun on the caveman culture of The Flinstones. Literal bedrock (or a reasonable simulation) covers a TV set—and, speaking of bone white, human bones fill out high heels. As for a proper chair, forget it. I sat on the floor, biding my time, drinking in the art.

One had better takes one's my time, for eight films play out on TV. They depict terrorists, exclusively from the right, with more than a hint that they already rule. Oh, and that iron curtain comes with a spiked baseball bat in place of the hammer in a hammer and sickle. Welcome to America. That near circle is actually a horseshoe and refers to the "horseshoe theory," that extremes of left and right bend toward one another, so that only the center is safe. Did you know George H. W. Bush played horseshoes with Boris Yeltsin—or that a horseshoe theory of design also circulates online, including designs for chairs?

There is a lot I did not know. Re-education, it turns out, was the title of a western program for East Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Communism may have collapsed, but George Orwell lives on. Those who claim the center also like to say that "there are good people on both sides," and Naumann hand-letters that as well. Whose side are you on? They asked, accusingly, during the Cold War, and they are asking again today.

Naumann was only a girl in Germany when the wall came a-tumblin' down. You might think that she could have little memory of conflict, although she surely heard plenty about it. You may think, too, that they would have instilled a lasting hatred of Communism. They might even have joined in celebrations of its fall. Apparently not. She sees a more pressing threat in the ideology of power today. She fears it all the more for its promise of comfort.

You may find all this tendentious as can be—and its plea for the power and politics of design way overblown. Then, too, you may find it simply puzzling, with allusions too difficult to catch and connections too slippery to believe. Still, the contradiction between moralism and obscurity has its benefits, in tempering either one. You never do know for sure where she stands, which only makes sense when neither Putin nor Donald J. Trump can face losing. Just be prepared for some awful puns, and try to laugh with them. This is your re-education, too.

No more heroes?

There are wars with few if any heroes and wars that no number of heroes can redeem. There are wars, too, in which everyone was a hero, but only because the loser's fall was terrible and swift. For now, though, the war in Ukraine is at a stalemate, with plenty to thank for the nation's holding out against all odds. Lesia Khomenko does her best to remember them, but her memories keep coming up short, as they must. They are vivid all the same. In a show called "Full Scale," the fighters are life size but never larger than life.

Khomenko has every reason to remember, and it can only hurt to try. She fled soon enough after the Russian invasion of February 24, 2022, but not before her partner volunteered in the defense. Now she must rely on online images much like the rest of us, in a war that would seem to exist solely in cyberspace, did they not include dead children, cities in ruins, and adults in tears. What if past wars had undergone this kind of scrutiny in real time? Would the fall of France to the Nazis have seemed any less inevitable or George W. Bush's mission in Iran any more obviously a lie? The world might do with fewer heroes even now and fewer excuses for war.

Khomenko has every reason to remember, and it can only hurt to try. She fled soon enough after the Russian invasion of February 24, 2022, but not before her partner volunteered in the defense. Now she must rely on online images much like the rest of us, in a war that would seem to exist solely in cyberspace, did they not include dead children, cities in ruins, and adults in tears. What if past wars had undergone this kind of scrutiny in real time? Would the fall of France to the Nazis have seemed any less inevitable or George W. Bush's mission in Iran any more obviously a lie? The world might do with fewer heroes even now and fewer excuses for war.

The artist is entitled to her hopes and her doubts. She knew at first hand protests against Russian puppet governments in 2014, followed by Russia's annexation of Crimea. She opens here with the face of a protestor, a woman, crying out from the blackness and shimmer of a light box. Its dense tumble of white lines may recall Alberto Giacometti and his gaunt figures, but their pain and anger are not just existential despair. Already images of war were part of an active art scene, and Khomenko had co-founded HUDRADA, a curatorial union, and joined the R.E.P. (or Revolutionary Experimental Space) group in Kyiv, to which she has returned. She appeared last summer with a more conventional realism in a show of Ukrainian women artists responding to war.

She is asking hard questions about war, at her own and her country's expense, but also about art's ability to represent it. Conventional reporting concerns drones and mercenaries, and her soldiers are no less faceless. They are Unidentified Figures, as if their camouflage had succeeded all too well. Her fragmentary browns and greens evoke their uniforms, but also Cubism, a style with little patience for illusion. Her broad brushwork and long drips bring them one step further from virtual reality and closer to her. They also dissolve unidentified figures into landscape or abstraction.

Are her warriors just empty suits? One outfit without a body appears downstairs, in a painting saturated with yellow and blood red. It lacks only a hanger, while a seated figure on the next wall has lost his head, too, or buried it in his hands. Both paintings glow from within, with a full moon that one could mistake for a hole, backlit, in the canvas. If this is a war zone, there is no escaping it, inside or out. Still, it shines.

Khomenko's Unidentified Figures seem determined to be heroes, bulked up like Ninja Turtles or Soviet realism. And that heritage casts doubt on art's redeeming power, too. Three last figures have lost everything but a prosthetic limb, but its pole amounts to canvas—painted, rolled up, and stuck in a shoe. More precisely, what may look like combat boots are only a boxing glove and sneakers. Is this war, too, only a lie, or have everyday heroes fallen back on what they have? It may depend on how long a stalemate can last.

Barbara Kruger ran at The Museum of Modern Art through January 2, 2023, and at David Zwirner through August 12, 2022. Henrike Naumann ran at SculptureCenter through February 27, 2023, Lesia Khomenko at Fridman through April 29 and in its show of Ukrainian women artists through April 26, 2022.