But Whose Struggle?

John Haberin New York City

Jacob Lawrence: American Struggle

Jacob Lawrence and Gwen Knight

Maybe you grew up thinking of America as the land of the free, where all men are created equal. Or maybe you know it as a nation founded on slavery—or founded to preserve slavery. For Jacob Lawrence, its history was nothing less than a struggle. Nearing forty, he offered his own account of the "American Struggle," at the Met, on display together with its anniversary show of "Making the Met."

Gwen Knight lay on her back, well past the back of her cat on the bed. She seems more dour than comforted by the company. It cannot have been easy for a painter married to Jacob Lawrence, but she holds her own in his sketch by the sheer force of his ink and her composure.  The greatest chronicler of black history to this day, Lawrence must have sucked up attention, even as he set the style for a generation of African American art. Now they have a face-off, too, on opposing walls in Chelsea, where she again holds her own. She brings a specificity to her art that his ambition precludes.

The greatest chronicler of black history to this day, Lawrence must have sucked up attention, even as he set the style for a generation of African American art. Now they have a face-off, too, on opposing walls in Chelsea, where she again holds her own. She brings a specificity to her art that his ambition precludes.

Epic journeys

Born in 1917, Jacob Lawrence was a student of history, and he retold it his way in his art. As a boy in Harlem, he headed to the city's museums for art history. At the Met, he could see The Journey of the Magi by Sassetta in the 1340s as not the privilege of the few and the great, but as the slow, epic journey of three men and their entourage. They descend across a small panel, from right to left, on their way to a miracle in Bethlehem. He, too, was to take up groups of figures—and groups of works, most notably The Migration Series from 1941, about the African American journey north. It hung next door at MoMA in 1995 from as daring a modern artist as they come, Wassily Kandinsky, and it had pride of place in full once more in MoMA's 2019 expansion.

He headed downtown, too, for MoMA and a notably American art history. He had a fondness for early moderns like John Marin and Arthur Dove, as the first halting steps toward an American century. Their jagged rhythms became the wild gestures and flattened figures in his journeys, too. At the Met in 2002, one could trace his discovery of the twin pillars of his art, the silhouette and the series. He wanted modern art to tell a story, the story of African Americans. If he borrowed elements of folk art as well, he sought an art befitting the common people.

As an adult in Fort Greene, in Brooklyn, he was still a student. He returned to Harlem many a day for its central library, now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. That was quite a trek as well, but it afforded a long view of American history. It also became research toward his art. He spent two years on Struggle: From the History of the American People (to give it its proper name), starting in 1954. Most of its thirty paintings bear long titles—quotes from his reading. Stretching from the first strivings for independence through the War of 1812, they, too, see history as an epic journey.

But whose history and whose journey? Lawrence would have rejected both choices, the land of the free and the land of white oppression, in favor of the struggle. Some have focused on white struggles, between abolitionists and slaveholders—or within the conscience of slaveholders like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson who could not bring themselves to free their slaves. Others insist on black agency in the struggle for freedom. Lawrence would have understood both, but he depicts blacks and whites fighting together, with truth on their side. Only they cannot hide their differences, and he ends with whites turning on people of color.

His sources were progressive histories, like that of Charles and Mary Beard, but not politically correct ones, not by today's standards. A Marxist, Herbert Aptheker, had compiled a documentary history with a forward by W. E. B. Dubois, the scholar and founder of the NAACP—bringing together champions of race and class. Does that make the series irrelevant for today? To make things worse, paintings went for sale and dispersed to the winds, one is too fragile to travel, and some are missing altogether. The Met presents three in faded reproductions. It leaves two more as blank rectangles on the wall.

Worse still, Lawrence may never have finished the series. It ended up abridged from a planned sixty works, stretching from European settlements through World War I. Even so, for some, Lawrence gave up the proper domain of his art. What of African American history—and what of its own time, the year of Brown v. Board of Education and the year that President Eisenhower integrated the military? Yet it sustains the style and the struggle of his best work. If it recounts a more distant history, the past, as William Faulkner wrote, is never even past.

The price of freedom

Struggle could be a prequel to The Migration Series or its fruition. Here, too, Lawrence adopts small paintings, each just twelve by sixteen inches, in tempera's flat, clashing colors. Here as well are bodies weary from the journey. Outstretched arms plead for dignity—or gesture in agony. The series opens with Patrick Henry's cry, "Give me liberty or give me death." His audience looks anything but certain which they will receive.

These are bodies in a mass and in motion, even when they huddle shrouded from the cold. They could at times be a single body in stop-action motion. That made sense for the Great Migration, but it makes more sense still for times of war.  When armies clash, they make it difficult to disentangle the sides or to declare a winner. Lawrence admired Mexican art and its demands for freedom, but he preferred the red and yellow grouping of José Clemente Orozco to the earthy heroism of Diego Rivera. And a survey of Mexican murals at the Whitney Museum returns the favor, including Lawrence.

When armies clash, they make it difficult to disentangle the sides or to declare a winner. Lawrence admired Mexican art and its demands for freedom, but he preferred the red and yellow grouping of José Clemente Orozco to the earthy heroism of Diego Rivera. And a survey of Mexican murals at the Whitney Museum returns the favor, including Lawrence.

Where The Migration Series has clashing limbs, Struggle adds clashing swords. They put down a slave rebellion during the Revolution, and they lie in a heap at the Constitutional Convention, where they give way to the rule of law while refusing to be left behind. Still, weapons for Lawrence are an extension of human strivings, with the outcome still in doubt. In the sole painting from the museum's collection, Washington does not cross the Delaware as in the Met's American wing, but only three small boats, with common soldiers and no room for standing. Not much blood spills, but it drips down the side of paintings where one least expects it. At the Boston Massacre, Crispus Attucks does not so much spit it out as spew it right onto the viewer.

Attucks, the first to die that day, was a black stevedore, and race does enter, again and again, even in a common cause. Lawrence, who served in the Coast Guard in World War II and completed his War Series in 1947, insists that African Americans forged America all along. Brown shadows color white faces as well. He also takes up the cause of Native Americans. As Lewis and Clark set out to map the Louisiana Purchase, Sacagawea as their Shoshone guide dominates the painting—lending the series its most colorful accents. By the end of the series, blacks, immigrants, and indigenous peoples will not fare nearly so well.

It makes for an impressive ending, just as Henry's cry for liberty makes for an impressive beginning with added resonance for blacks. In the last panels, peace is finally at hand, although the British have set fire to the young nation's capital. Just when formal battles have ended, whites like Andrew Jackson are turning on others. The last three paintings are among the missing. Maybe collectors did not wish to hear the dying voices. Look back at the entire series, and it is no longer a history of white America.

Did Lawrence really give up the story, or did he find its shape as he worked? He did not just pare away colonial America and subsequent wars. From the original list of sixty works, in a Guggenheim grant proposal, he also cut battle after battle, in search of moments that aspire to more. Sure, The Migration Series is a tale of liberation, while this is tale of only struggle. Still, neither turns away from the aspirations or the agony. As I wrote after the Lawrence retrospective in 2002, the price of freedom is that one may not find one's bearings.

Killing time

Is that Gwen Knight, too, by her own hand, her red lips and blackened eyes less a come-on than a mask? If so, she kneels on a round blue cushion as if knee deep in troubled waters. Still, she poses only for herself. Women may be incidental to Lawrence's "American Struggle," his series from the 1950s, but not to her, no more than to portraiture for Benny Andrews. A diva cannot leave her voice in paint, but she creates a greater drama all the same with her hands.  They move upward from the fullness of a red dress, and so does her flaming yellow hair.

They move upward from the fullness of a red dress, and so does her flaming yellow hair.

Born in 1913 in Barbados, Knight reached Harlem at age thirteen, with a detour to Howard University in Washington. Like Winold Reiss, she knew the leading lights of the Harlem Renaissance and assisted Charles Alston on a mural for the WPA. The Works Progress Administration also introduced her to Lawrence, four years younger, and sponsored his "Migration Series" as well. Did her career take a back seat to his, like their reputation today? She followed him to Seattle when he got a teaching job in 1971. Still, only then did she begin to exhibit much, and she had her first retrospective at age ninety, before her death in 2005.

She has fewer works on view now than Lawrence, too, as if to rub it in. His sketches set the tone for paintings apart from any series, in a less familiar place between the personal and the political. Assassination from 1965 in ink depicts the point-blank shooting of one black by another, and three more bodies have already fallen between them. They are just cogs in America's killing machine, but they cannot help recalling the deaths of John F. Kennedy before them and of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., yet to come. In a painting, the stalk of a flower looks like a scythe for the grim reaper, and a black mass on the red tablecloth looks like a shroud. More flowers lie dead, and a clock has lost all the numbers past 3.

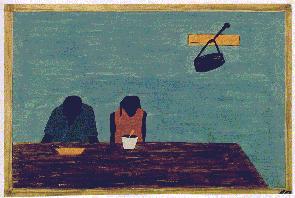

Lawrence calls it Time, and he is always taking the long view. The paintings chronicle a people, even when they aim for the everyday. A man plays solitaire, the ultimate in killing time, but he could be staking his life. A supermarket, in a painting subtitled Celebration, could pass for a city on the verge of a riot. Colorful but faceless men in a beer hall form three tiers, connected by rich brown floor beams and risers. They could be part of a joyful or tragic pageant.

It is hard to know whether to call the colors dark or bright. Their heightened contrasts recall Romare Bearden, but without Bearden's roots in jazz and the street. And Knight adopts Lawrence's tempera and his palette. Still, her directness comes as a relief from the demands of history. For him, even a game of pool is an epic confrontation. For her, a flower is just a flower and a woman a woman—and someone she has come to know.

A young woman in white leaves it to the red sphere in her open palm speak for her. Her dark skin serves as a bridge from the wall in front of her to the shadows at her back. Not that Knight has put blackness behind her. A painting from 1945 takes her back to Barbados, where a road winds along the shore. Rooftops echo the red of distant hills and a patch of light on the beach, and the silhouettes of trees lean toward against white breakers and a darkening sky. It will take a larger show all her own to see how her memories would play out.

Jacob Lawrence ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through November 1, 2020, he and Gwen Knight at D. C. Moore through March 27, 2021. Two of the five missing paintings have now surfaced, thanks to publicity from the Met's show. Related articles look at Lawrence in retrospective and his "Migration Series."