The Way Home

John Haberin New York City

Marsden Hartley in Maine

Where We Are at the Whitney

In his last years, Marsden Hartley tried to remake himself as, in his words, the painter of Maine. It would have surprised his most ardent admirers, but then he still could not get over his fears of banishment. Maybe the Whitney Museum would understand. It gives its permanent collection a home as "Where We Are," but with full awareness that no understanding of art or America is permanent.

The Whitney alludes early and often to a poem in the darkness of a world at war, and it opens with paintings about a previous war. Yet it has space for the comforts of home, including two different paintings of room heated by a stove. It has no room for Stuart Davis and American Cubism, some of the leading lights of the Ashcan school and Abstract Expressionism, or the showpieces of Pop Art, but repeat appearances by Edward Hopper and a renewed emphasis on race and gender. Who we are, then, is changing, but not all at once, which is only reasonable. It is less out to change the face of American art than to change how one sees it. In other words, it is even now looking for home.

Remember the Maine

Marsden Hartley looked for home in Maine. He sought a sense of place in its mountains and shores. He sought a sense of community in its churches and farmsteads. He sought its livelihood in its lumberjacks and Acadians. At age sixty, he was returning after a lifetime of fresh starts and unanticipated displacements. Is it any wonder that he ended up painting only turmoil and longing?

Hartley is better known for just that turmoil and longing, only in another country and in wartime. The painter of Maine made his name with paintings of German military gear and the iron cross. Their thick lines and strong contrasts between bright yellow, red, and black have ties to urban American realists like George Bellows and John Sloan. Yet they have only gained attention since then, with the seemingly postmodern reduction of a "portrait" of a German officer to surfaces and signs. They have also taken on a greater relevance with their frank homoeroticism. "Marsden Hartley's Maine," though, focuses instead on landscape all but devoid of humanity.

He took a long time to find a home. Born Edmund Hartley, he lost his mother while young, followed family to Cleveland in his teens, studied there and in New York, introduced himself to modern art in Berlin and Paris, and exhibited with Alfred Stieglitz in a gallery devoted to American Modernism. For yet another disappointment, he broke with Stieglitz as well because he would not settle in New York. Even after World War I obliged him to leave Germany, he kept traveling. He saw Maine's Mount Katahdin through the lens of the Alps and of Mont Sainte-Victoire for Paul Cézanne. He saw its seacoasts and storms through Winslow Homer and Japanese prints.

Still, he had reclaimed Maine as his own once before, earning him such champions as Edith Halpert. He moved back for a while around the turn of the last century, and he joined an artist colony that encouraged an interest in American folk art. There he painted on glass along with his favored paper board and Masonite. As curators Randall Griffey, Elizabeth Finch, and Donna M. Cassidy map the connections and disconnections, and the show falls in two with a huge gap in between. The first half amounts to barely four years starting in 1907, the last from 1937 to 1942. Within those divisions, it proceeds less chronologically than by style and theme.

That can suggest an artistic development that is just not there, but it clarifies what drew Hartley to New England all along. He starts with a dark, thickly textured, and nearly monochrome seascape, on loan from a library in Maine, and blackness keeps asserting itself in his art. Even when he picks up Post-Impressionism a bit late in the game, well after Félix Fénéon, the bright colors add up to twilight. They also give way to Dark Mountain, a series inspired by Albert Pinkham Ryder. He is already adopting his characteristic composition as well—dark masses surrounding pools of light, framed by brighter strips for earth and sky. Clouds at top appear disturbingly large, and houses or farms along the bottom appear unnaturally small.

They create a scene of abandonment—only intensified by the greater realism of his late work. When he paints a church, it appears as a white wall pierced by dark windows, set unstable and askew. When he paints breakers, they rise in a torrent. When he paints logging country, he finds imposing piles of timber or a logjam. When he takes up still life, a white seahorse looks larger than life but unmistakably dead. When he paints the view out a window, its brightness seems cut off irrevocably from the interior.

Hartley has found a more muscular art. He learns to use longer brushstrokes, tarter reds and blues, and black outlines as shadows. If they invite one to compare the landscape to a human body, he still has his undisguised longings, and he paints them, too. Loggers appear face-on in little more than small swim trunks, arms akimbo after Cézanne's bathers. Who knew that workmen could cavort half-naked, with reddish-orange flesh? He could be unsettling masculinity or fixated on it.

Does he keep finding models in art at least a generation after their time? For all his appeal, Hartley remains deeply conservative—never quite able to engage Cubism or Henri Matisse. A black duck looking suspiciously like a woman in evening wear stops just short of German Expressionism. Then, too, though, his always stopping short adds to the sense of exile even at home. Katahdin means "highest land," and he made plans for High Spot, a house to call his own. He died in 1943 without completing it.

Who we are as well

It has taken a few years, but the Whitney has found its way home. Maybe it never could find its way back to Madison Avenue, obliging the Met Breuer and then the Frick Madison to pick up the pieces—at the cost of a balanced budget and a director's career. Maybe it felt a bit lost in the Meatpacking District, reopening in Renzo Piano architecture with "America Is Hard to See." Now, though, after a stormy Whitney Biennial, it has taken a liking to what it sees. It even calls a rehanging of the permanent collection through roughly 1960 "Where We Are." This being a museum of American art, naturally it has to assess who we are as well.

It takes its title from an exile in America, W. H. Auden, but the British poet opens "September 1, 1939" with a chilling specificity of time and place:

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade.

It has become something of a cliché to say that this or that warning hits home in age of Donald J. Trump, but Auden's does. As curators, though, David Breslin with Jennie Goldstein and Margaret Kross are at least cautiously optimistic about home ground. Their five rooms borrow further from the poem, for familiar themes of American aspirations— "No One Exists Alone" for family and community, "The Furniture of Home" for domesticity, "The Strength of Collective Man" for labor and industry, "Of Eros and Dust" for the greater longings of postwar art, and "In a Euphoric Dream" for American icons. In this company, a near abstract riff by Larry Rivers on Washington Crossing the Delaware looks less like a shriek of pain than the sheer pleasure of painting.

"No One Exists Alone" for family and community, "The Furniture of Home" for domesticity, "The Strength of Collective Man" for labor and industry, "Of Eros and Dust" for the greater longings of postwar art, and "In a Euphoric Dream" for American icons. In this company, a near abstract riff by Larry Rivers on Washington Crossing the Delaware looks less like a shriek of pain than the sheer pleasure of painting.

Auden would have had his doubts, to judge by the context of a quote: "but who can live for long / in an euphoric dream." You are entitled to your doubts, too. Museums rehang their collections all the time, as the Whitney did for its seventh-fifth birthday—and I have not even bothered to write up work from the 1980s on another floor or at MoMA. The wall text, too, can sound phony, in comparing "the rural Kansas of his youth" for John Steuart Curry to "the mother he lost" for Arshile Gorky. The double portrait of Gorky and his mother, who died in the Armenian genocide, has a monumental blankness that Curry's regionalism could never attain.

Within, though, Curry's Baptism in Kansas hangs next to an equally ecstatic religious community bathed in a blue light from Archibald Motley, the black artist in Chicago. A trite history has given way to diversity and feeling. The same comes in the room for "collective man," where linoleum cuts by Elizabeth Cattlet pronounce I Am the Negro Woman. Right off the elevator lies another recent acquisition of African American art, the war series by Jacob Lawrence. It puts on equal terms the pain of soldiers and artists in World War I and of families learning of their death at home. Look off to the side, to a parade in Washington Square by William Glackens, and its sentiments look a lot more suspect but its dabs of color more modern.

Women appear again to the other side, where as unfamiliar a name as Agnes Pelton under the influence of theosophy leads to a glowing abstraction by Georgia O'Keeffe. A pair of eyes by Jay DeFeo hangs next to a Veil by Morris Louis, as if looking behind the curtain. Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and Margaret French supply another kind of diversity, in collaborative photos of gay identity as PaJaMa. White males can add surprises, too, like Andreas Feininger. His photo of a house brought in one piece to suburbia seems torn between assertions of rootlessness and home. Speaking of home, I had forgotten that Edward Hopper also painted East River apartments.

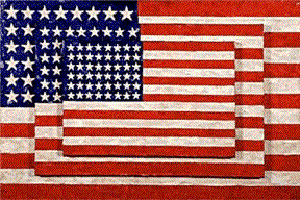

Icons like Hopper and Jasper Johns still have their place. In fact, Early Sunday Morning and Three Flags have a wall to themselves, just in case you had never noticed that the first has its own red, white, and blue—in the shape of a barber's pole. So does an abstraction by Ellsworth Kelly. A black painting by Frank Stella appears with scenes of white working-class America by Charles Demuth, Elsie Driggs, Margaret Bourke-White, and Dorothea Lange because, among other reasons, Stella applied house paint. But picking winners gets old quickly when it comes to the permanent collection. Even Auden ends his poem with an "affirming flame."

"Marsden Hartley's Maine" ran at The Met Breuer through June 18, 2017, "Where We Are" through June 2, 2019, at The Whitney Museum of American Art. A related review looks at a rehanging of the Whitney's collection in 2019.