Is There a Female Gaze?

John Haberin New York City

Juergen Teller and Janine Antoni

Is there a female gaze? If so, what would it look like, and who would it see? Would it see a pink fabric couple having anal sex over a slab of cold steel? The question may sound more like metaphysics or a lousy sexist joke than gallery-going. Yet it goes back to one of the most influential ideas in contemporary art.

For feminist criticism, men looking at women has become a pretty good and pretty sad summation of art history—a history in which women's bodies are never their own. It may seem impossible to keep putting new twists on the story. And maybe it says more about the mess of contemporary culture than about the vitality of contemporary art, but artists do so all the time. As fall 2009 hit the galleries, a male photographer staged the most blatant parody of the male gaze. And he did it with a fashion model and actress. Juergen Teller does it more dutifully than creatively, but he does so all the same.

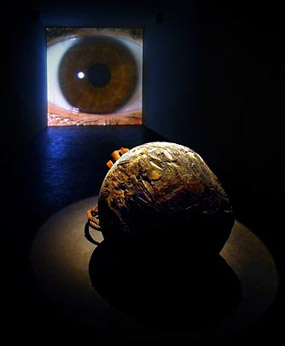

Meanwhile women are making a point of looking at and for themselves. Janine Antoni, for one, turns the video camera on an enormous eye. And an oversized gallery survey of "The Female Gaze" collects women looking at women. It never quite sorts things out, including whether "the female gaze" actually exists. It even has a male curator. Still, it is sure to have both men and women looking.

Night in the Louvre

Feminists (like me) often have a problem with museums, summed up in a handy catch phrase, the male gaze. It means too few women artists, too many male viewers, too many women in a dollhouse, and too much willing female flesh. One could imagine the adolescent male version, as with Jim Shaw—too few superheroes and too few real naked women. Or one could imagine an all too human and scared adult male version, as in the photography of Alfred Gescheidt. Juergen Teller has an answer. He provides the R-rated version of Night in the Museum.

It still might disappoint kids of all ages. Nothing comes alive after hours after all, and no one reveals the da Vinci code. Teller photographed Charlotte Rampling, the actress, and Raquel Zimmermann, the model, stark naked in the Louvre. They stand erect beside towering Greek gods and heroes. They loll against the guard rail protecting the Mona Lisa, as if waiting for the action. If they looked any more detached, they might be Photoshopped in.

Art can shove your desires in your face—or more quietly pick apart your expectations. It can also end up reinforcing them. To get fancy about it, one might call these possibilities parody, deconstruction, and redoubling. Maybe any critique of anything has a hand in all three, but Teller definitely does. The parody part is easy enough, especially with such stately and enigmatic nudes. One can almost hear him shouting, a little desperately, "Get it?"

More quietly, no one behaves quite as expected. The Louvre turns out to hold mostly male nudes, not the male gaze, and the women upstage them. They also do everything they can to keep cool. Meanwhile the camera lingers over a statue's white male thigh. In another photo, a god or satyr thrusts his hand into a creature's innards. Nothing identifies the statue's gesture as an appetite for violence or just for meat.

The women could easily pass for mother and daughter. That adds another enigma, and it undermines the old obsession with youth and beauty. Yet for all that, the stars make an awfully attractive pair, as part of an awfully slick presentation. The show's title, "Paradis," may sound like mockery of fine art as an unspoiled paradise. In practice, it means that Teller staged all this for a glossy publication of the same name, un magazine pour l'homme contemporain." In English, that means lots of fashion shoots and naked women.

One can enjoy and admire Teller's mockery, but also art's paradise by the dashboard lights. The women redouble the flesh and the poses behind them. Even their age difference, despite perfect bodies, echoes the supposed timelessness of art. A photo of Napoleon Crowning Josephine, a sad show of conformity by Jacques-Louis David akin to his Napoleon crossing the Alps, does not gain all that much critical distance from a spot washed out by Teller's flashbulb. Still, for the most part Teller's strangeness wins out, at least with Rampling and Zimmermann in the picture. These nudes hate to give anything away.

In the blink of an eye

Janine Antoni puts herself into her work. As early as 1992, one could call her work performance art, but she presented it as sculpture. She carved Gnaw not in marble but in chocolate and lard—and not with a chisel but with her teeth. Her Saddle of 2000 shaped the rawhide into a fallen or degraded woman. The shapes, the materials, and the process all invoke a woman's body image, like self-portraiture for Brenda Goodman, but nothing privileges her anxieties over the viewer's. Nothing, that is, but her way of turning them into art.

Performance often has macho overtones. No wonder Carolee Schneemann and Mika Rottenberg adopted it for feminism and new media. When Chris Burden drags himself across broken glass, Matthew Barney scales the Guggenheim, and Tehching Hsieh punches a time clock for a year, they boast of their "Endurance." Antoni concluded a 2003 performance, a plain old tightrope walk, simply by falling. Even when Marina Abramovic turns performance art into an act of submission, naked on a gallery shelf, she stares back. Face to face with the viewer, Antoni blinks.

She blinks thunderously at that. Every blink of an enormous video eye (no razor blade in sight) lands with quite a thud. For all that, she is not above laughing at it, and nothing identifies it as hers. The wrecking ball on the floor could monumentalize the eyeball, stare it down, threaten it with destruction, or drive it to tears. The work's title, Tear, cuts both ways. The ball has seen better days, but so have a lot of people.

Her show's title, "Up Against," could have her taking a stand or just "up against it." A handful of copper gargoyles peer out from their pedestals, more like pet geckos than architectural wonders, and in a photograph she pees through one. Antoni could be taking on male superiority, working through penis envy, or fighting off animal interest in her crotch. One new photograph straps her in a harness, held up by ropes resembling a spider's web. Like the geckos, it plays against the old identification of a woman's body with nature or altogether another world. It stands for entrapment, too, and so could the ball and chain.

It also associates her with domesticity, by framing her thighs with an oversized dollhouse—and by framing the entire scene with an actual interior. The spider web is one of many references in her work to weaving. The 2003 tightrope spun out from an industrial drum and across the gallery floor, like a loose spool of thread. After a 1994 performance, Slumber, she knitted the pattern of her brain waves into a blanket. An earlier tightrope walk, in 2002, made her seem to walk on water, and she speaks of her work as a search for balance. Plainly balance is hard to come by.

Antoni insists on a woman's agency, like Mira Schor or Joan Semmel, but she takes the consequences in stride. Her themes themselves form a loose weave. They can leave her shows too cryptic or too clunky, like leftovers from an opening-night performance that few will ever see. Just as often, though, that refusal to have the last word helps her shed roles as quickly as she embraces them. It leaves her a supporting actor in her own work, and few artists are so at ease in the role. As she pees on a balcony, she has the star quality of a fashion shoot.

Women beware women

When it comes to gender, Teller and Antoni may not point the camera in every conceivable direction. Still, taken together, they do point it every which way when it comes to gender. Is there anything left? Should there be? A gallery survey of women looking at women seems to think so. Maybe or maybe not, but it allows a kind of summing up of the story thus far.

In a way, art history begins with cult objects with big boobs. At least since the Renaissance, painters have lingered over the female nude, too, but with a more secular intent, although Gian Lorenzo Bernini did his part with The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa fully clothed. And at least since Judith Leyster in the Baroque, women have demanded the right to stare back. For Artemisia Gentileschi, make that fight back. With Manet's Olympia and Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, a woman's stare drove Modernism's rebellion. With feminism, it insists on still more.

In a way, art history begins with cult objects with big boobs. At least since the Renaissance, painters have lingered over the female nude, too, but with a more secular intent, although Gian Lorenzo Bernini did his part with The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa fully clothed. And at least since Judith Leyster in the Baroque, women have demanded the right to stare back. For Artemisia Gentileschi, make that fight back. With Manet's Olympia and Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, a woman's stare drove Modernism's rebellion. With feminism, it insists on still more.

"The Female Gaze: Women Look at Women" backs off from asking just how much more, but it leaves an intriguing trail of evidence anyway. In a much-cited 1975 essay on Alfred Hitchcock, Laura Mulvey saw a man with a camera riddled with lust and fear—a vision that Daniel Canogar on video has since made vivid and Barbara Probst in photography has made a woman's art. Art, like its subject, was a male product, a fetish object, and a basket case. Women take charge of recovery, and they do not simply stare back. Women do the looking, and they do not so much as bother to look at men. That creates a superficial unity, but also puzzles of its own.

John Cheim, the curator (and, yes, male), finds women lingering over ideals of female beauty as long ago as Julia Margaret Cameron, the Victorian photographer. Well before Charlotte Rampling, Cameron already photographed an actress, Ellen Terry. Roni Horn, in her photographs of Isabelle Huppert, merely updates the ideal for a more critical, self-aware era. So do Marilyn Minter, Lisa Yuskavage and Yuskavage drawings, and Ghada Amer, with their very unidealized takes on soft core. The forty artists includes the proudly self-obsessed, like Tracey Emin, and the smartly self-critical, like Cindy Sherman. They also include artists that one hardly associates with a woman's point of view.

That is what makes show so ingenious, but also disingenuous. What exactly has changed when a woman looks at women, and what has not? For Diane Arbus (particularly early Diane Arbus), Catherine Opie (particularly Opie's portraits of artists), or Alice Neel, men would look just as sympathetic and just as creepy. For Marlene Dumas or Kara Walker, they would look just as much the victim of oppression. At least I think they would. The show does not offer a basis for comparison, and it hardly could without losing focus.

Should one care that the focus is itself the product of someone's gaze? Probably. Call it a formula or a cop-out, but it is still a surprise—like that pink fabric couple by Louise Bourgeois. Easy summer pleasure or not, it does give women the last word. When Abramovic says Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful while combing her tangled hair, every stroke hurts. But it is, and she is.

Juergen Teller ran at Lehmann Maupin through October 17, 2009, Janine Antoni at Luhring Augustine through October 24, and "The Female Gaze: Women Look at Women" at Cheim & Read through September 19. A related review looks at other ironic practitioners of the male gaze, Alfred Gescheidt and William Copley.