Homage to Child's Play

John Haberin New York City

Art Brut in America

Jean Dubuffet and Ronald Lockett

For a time, long before Postmodernism and Outsider Art Fairs, outsider art came to America. It came big time, too, and at a pivotal time and place. "Art Brut in America" argues for an overlooked influence on American art, just when New York was becoming art's capital of the world.

It was a personal triumph for Jean Dubuffet, who had amassed quite a collection. But did it change the course of art? Probably not, although his drawings show him torn between the child and madman. Yet they also show him torn between outsider art and the mainstream. As for Ronald Lockett, he may have felt like a deer trapped in the headlights. The last thing he expected was fame—not even the recognition that comes now at a museum dedicated to outsiders.

Art cute

In December 1951, twelve hundred works of outsider art went on display in East Hampton, at the far end of Long Island, thanks to Jean Dubuffet. He had placed them under the care of Alfonso Ossorio, born in the Philippines (the country of Enzo Camacho and Ami Lien) and himself something of an outsider in the New York School. There Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, and Franz Kline could drop in for a look—and so could Clement Greenberg, the critic who made the case for them as the ultimate in modernity. No one can know what they felt and what they saw, but the American Folk Art Museum subtitles its show Dubuffet's "incursion," with overtones of a hostile raid. The Frenchman boasted of the collection as "uncontaminated by artistic culture" and "contrary to . . . intellectuals." Greenberg, an intellectual who saw Abstract Expressionism as the triumph of Modernism in America, could have taken that boast personally.

Dubuffet massed his troops quickly, much like many folk artists and collectors. The collection began only six years earlier, when he came upon a psychiatric patient's sculpture in Switzerland, and it grew to include the paradigms of art and madness in Heinrich Anton Müller, Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, and Adolf Wölfli. It returned to Europe in 1962 and became the Collection de l'Art Brut in Lausanne in 1971. Müller marks one pole with his childlike drawing and anxious objects, like the wiggly outline of a man next to a snake. Wölfli marks the other pole with his crowded detail and broken symmetries, centered on shrieking faces, decorative patterns, exotic birds, and a musical notation all his own. Between their stick figures and horror of a vacuum, Dubuffet found an ally and a model.

Few will recognize others in the collection, their anonymity enhanced by wall labels too low to read without stooping. Surely Greenberg would have seen not an alternative to modern art's straight and narrow, but a leveling. He might also have seen it as a throwback. Early Modernism had embraced "the primitive," like Pablo Picasso in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, without caring all that much for the particulars of other cultures. In the 1950s, artists were freeing themselves from just that, Greenberg would have said, like Pollock finally setting aside Surrealism for abstraction. Did they discover in the Hamptons an influence—or only a mirror of what they had left behind?

The question has new relevance now that outsider art can "break on through" to the downright respectable—in the case of Eugen Gabritschevsky, even embracing science and Morris Hirshfield Surrealism. Critics are seizing on it as less an alternative than an erasing of boundaries. Maybe MoMA still sees it as "the other," as in excluding Janet Sobel, perhaps the first drip painter, from a display of Abstract Expressionism. Others, though, are less willing to distinguish outsiders from the mainstream. They see the boldness in such African Americans as Jacob Lawrence, for whom folk art is neither raw nor primitive, or Carol Rama in Italy. Dubuffet's stress on the "purity" of his artists may not sound so contemporary after all.

There is Art Brut, and then there is art cute, and Dubuffet's own painting has way too much of the latter. Still, he could have learned something from his collection, and so can viewers today. Labels notwithstanding, Valérie Rousseau arranges the show by artist, interrupted by documentation. She keeps to relatively few in so large a collection, so that the differences stand out. Along with Müller and Wölfli, they include Ossorio, who slathers color on shaped panels. He also leaves the curved edges unpainted, like an artist's palette.

Berthe Urasco sketches women in old-world hats out of German Expressionism, while Auguste Forestier carves men in uniform from wood, like civic authority as a puppet show. Francis Palanc accompanies abstract geometry with squiggles, like handwriting in a language that has lost its voice, while Jeanne Tripier overlays ink blots on text. She also incorporates sugar, while Palanc builds his paintings from finely crushed egg shells, for a rough surface akin to Celotex for Richard Artschwager today. Juliette Elisa Bataille's knitted wool has the coarseness of tangled yarn for Judith Scott, an artist beset by mental illness now. They are not likely to become textbook names any time soon. They do, though, open a dialogue with Dubuffet about just who speaks for outsiders and for art.

The child and the madman

"I must learn how to draw." Writing in 1944, the year of his first solo show, Dubuffet may have had in mind a new dedication to his art. Born in 1901, he had taken classes in his student years, but he had focused until 1942 on earning a living, like many an aspiring artist today. Now the family wine business was doing well enough to allow him to take chances. Still, he sounds awfully like that annoying friend who keeps promising to take up guitar again, seriously this time, or to quit drinking and lose weight. He sounds, in fact, very much like the artist who, for all his skills and for all his success, would just as soon paint like a child.

His drawings at the Morgan Library show him grappling with his medium, but also with his own sophistication. The very first drawing, from 1935, pictures a woman by a window out of Henri Matisse—but with the rigidity and pallor of a doll. "Funny noses, big mouths, crooked teeth," he wrote on turning to portraits soon after World War II. "I like that." Yet his subjects were artists, poets, intellectuals, and friends. And what sounds like a childish glee in caricature works itself out on paper as emotional turmoil.

Yes, the American Folk Art Museum has followed Dubuffet as he brought outsider art to America, itself rich in folk artists like William Matthew Prior in its permanent collection. And yes, it showed his Art Brut as way too close to art cute. That indeed helps account for his popularity in painting and public sculpture.  His drawings, too, reward a search for the origins of his mature style, as curated by Isabelle Dervaux, but more provocatively. On paper, he begins to set aside single figures or single scenes only in the 1950s, moving instead toward interlocking curves and the edge of the paper. Still, outsiders to him meant children and psychiatric patients, and the joy of one had to stand against the torments of the other.

His drawings, too, reward a search for the origins of his mature style, as curated by Isabelle Dervaux, but more provocatively. On paper, he begins to set aside single figures or single scenes only in the 1950s, moving instead toward interlocking curves and the edge of the paper. Still, outsiders to him meant children and psychiatric patients, and the joy of one had to stand against the torments of the other.

That dynamic includes his oscillation between color and black and white. At first he deals with Paris under the German occupation in color, with the accent on the everyday. Life goes on, including the Metro and a jazz club. The riders keep up their smiles, for all their watchfulness, and the musicians could pass for a parade. And then Dubuffet changes the subject, along with his media, to nudes scratched into ink on gesso. Their flattening looks like an act of violence, and the white of their breasts looks like burning.

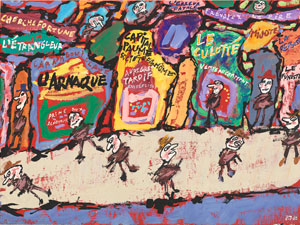

Still, he seems to have had a harder time coping with peace, as with the portraits, and he flees postwar austerity for North Africa and a return to color. Camels alternate with palm trees in a comic slow dance, much like his earlier pedestrians between trees by the Seine, and the Bedouins bare toothsome grins. Are they a charm offensive, a threat, or just victims of Dubuffet's orientalism? Probably all three, and a last return to color after 1960 comes with its threats as well. A Paris shop sign shouts Le Funeste, or fatal, and an entire street bears the title L'Armaque, or the swindle. Still, he sticks mostly to made-up words, perhaps as part of the swindle, and he shares with the gamers a sense of play.

In between, through the 1950s, comes the greatest blackness and by far the greatest density. An ogre can approach abstraction, while an abstract drawing can disguise a footprint or a face. The artist loses himself in a beard or "botanical elements," including leaves and butterfly wings pressed against paper. He is still playing around, though. The beards may be "watchful" or "majestic," and the leaves culminate in a Baptism by Fire. The child and the madman have to live together on a single sheet.

Has Dubuffet learned to draw? Has he learned from Paul Klee or Alberto Giacometti? Perhaps. From Surrealism? Definitely, and he had known André Masson long ago as a student. At the very least, he has become recognizably himself—and the show leaves off in 1962, more than twenty years before his death.

Trapped outside

Ronald Lockett wrestled with even the modest recognition that he received in his lifetime, before his death in 1998 at only thirty-two. "Try to keep an open mind," he said in an interview. "Try to stay the same." The advice sounds downright contradictory. He stuck to it anyway. He kept finding new ways to work with his materials, in seemingly whatever came to hand, and he kept returning to the same motif, a stag or deer.

Lockett may cut tin into its shape before adding color, or he may paint on plywood, where the deer can acquire horns. Either way, it is likely to find itself along with twigs behind a chain-link fence, as what he called his Traps. Trapped, yes, but also a force of nature and a sly work of art. A backdrop of corrugated metal may add that much extra force, while a painted forest may add its murky depths. Lockett may reverse black and white as in a photographic negative, even without Art Brut photography or Czech Art Brut, so that it shimmers in the night. Amid a further selection on the Lower East Side, the white animal looks more like a dog—and it turns its head as if trapped in the headlights.

Trapped, again yes, but also simply on the other side of the fence, like a proper outsider. Outsider art keeps getting harder to define, but Lockett has every claim to outsider status. He worked in Alabama, as a gay African American, and he died of AIDS. And his retrospective does everything it can to claim him for folk art. The curators, Bernard L. Herman with Valérie Rousseau, include tribal objects about as far from the Gulf as possible, from Alaska—as well as Sandra Sheehy, who embeds glass in stone like geodes or jewels. Still, Lockett found a mentor in Thornton Dial, a much older cousin who broke the New York art scene wide open. Like Archibald Motley, he could also boast of sophistication and skill.

His was not thrift store art, but appropriation, with knowledge and wit. The hose from a vacuum cleaner becomes the trunk of an elephant. A block of wood becomes the table at the Last Supper, with deft brushwork for the poses after Leonardo. Lockett took, too, to drips after Pollock, and his brush moves as easily as the scissors he applied to tin. White pushes into black and color into color, so that almost anything can resolve into an animal or a ghost. Elsewhere, rusted metal will challenge anyone to find the ghosts, in what approaches abstraction.

Folk art also suggests isolation, with the animal as alter ego. Perhaps, although Lockett is the one trapping them in the headlights. He knew the sufferings of others as well. Paintings invoke the Holocaust, Hiroshima, toxic waste, the Oklahoma City bombings, and more. In turn, he could count on support from family, particularly from a great aunt who lived past one hundred. An assemblage in her honor has the colored grid of late Modernism—or a quilt.

For all that suffering, a title can sound too sunny for its own good: You Can Burn a Man's House but Not His Dreams. It helps that he was not above playing with the dreams of others, as with his tin Adam and Eve admiring a landscape close to popular illustration. It helps, too, that he insists not on an edenic future, but the dream. When he calls a work Once Something Has Lived It Can Never Really Die, he suggests a spiritual life—much as the skeletons in his Holocaust rise from the darkness like spirits. The museum calls its retrospective "Fever Within," after a bright yellow portrait or self-portrait, because the fever lies within.

"Art Brut in America" and Jean Dubuffet ran at the American Folk Art Museum through January 10, 2016, Ronald Lockett at the American Folk Art Museum through September 18 and at Sargent's Daughters through July 15. Dubuffet drawings ran at the Morgan Library through January 2, 2017. A related article looks back to Dubuffet's sculpture as public space for art.