Forget March Madness

John Haberin New York City

The 2023 New York Art Fairs II

What drew me back yet again to the art fairs? What draws anyone back?

The fall New York art fairs seem more the new normal than ever, most on that first week after Labor Day, when summer for the likes of us has ended, and people are back in town. Galleries have their one week of concerted openings. (They can almost make up for empty office space, give or take reality.) So what more can collectors ask? How about two more trips to the Manhattan waterfront, for the Independent at the southern tip of the city and Art on Paper off the Lower East Side? How about two fairs in the Javits center alone—the Armory Show and a newcomer, Photofairs?

How about the buzz creeping into midtown for Spring Break (like the rest, formerly in March)—or alternative fairs in Chelsea itself? I swore this year that I could give them all up, but I could not let go of a favorite or two, and then the lures of photography and authority took me in. If I cannot do justice to any of them, you will understand. If I am frantic to catch up with the galleries and museums as well, you will again. Surely someone or something will not go along with this. It just will not be the business of art.

Better than a fair?

Is Salon Zürcher better than an art fair? It may seem so after a long day at the fairs, when pretty much anything would come as a relief. It began by inviting Paris and New York galleries into its host, Zürcher gallery. For four years now, though, it has become no more than a group show for fair week. It also devotes itself to eleven women, a changing eleven each time. If that does come as a relief rather than an irrelevancy, credit where credit is due.

The gallery has a weakness for abstract artists, as do I—here all except Elizabeth Bisbbing, with sunny interiors in cut and collaged paper. If a silhouette breaks the mood, it is because they are lived in. Abstraction leans toward the play between two dimensions and material space. For Ilene Sunshine, that means what critics used to call drawing in space, with the wiry outlines of twigs and colored thread. For Susan Schwalb and Agathe Bouton, it means working small, with metalpoint on thick panels and gold thread atop the grid. Schwalb's pencil adds like the soft shadows of her horizontals, while Bouton's small, square monotypes hang together like a deep blue empty dress.

For Colleen Herman, Elizabeth Velazquez, and Lauren Ball, it means working large, in the spirit of postwar abstraction. Herman applies garden color to white fields, like Joan Mitchell but with splotches akin to poured ink. A small, stacked sculpture takes on a new life for Velazquez, with light traces on tar black, while Ball's purple curves allow an otherwise unseen object to take shape. For Kristin Jones, a pen serves as a pendulum, while "the wind does the rest"—or the wind, gravity, and the laws of motion. Circles look like suns or moons with radiant edges. Margie Neuhaus wraps things up with thread, a long weave that seems to ravel and unravel before one's eyes, while drawings and an almost bare frame suggest the impulse that brought them together.

Will midtown offices after Covid ever return to life? One art fair has never left. If a dedication to work sounds odd for Spring Break, this is a fair for action and for fun. In its third year on Madison Avenue, it spills out from two high floors of offices and across common space. A room of handmade flowers greeted me off the elevators, by Christina Massey—and then came two sets of puppets (cuddly and black cowled), gas pumps, a bubble-wrapped cubicle, tunneling video, a Ferris wheel, and toys scooting around the floor. What other fairs would call "special projects" are here the norm.

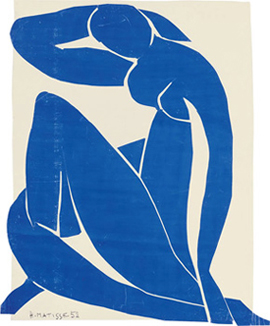

Sure, it has painting, lots of it, suspiciously like uploads to TikTok, although Peter Gynd brings the broad brush of gestural abstraction to small sunlit landscapes and Faustine Badrichan paints a credible imitation of Matisse cutouts directly on the wall. (I show the real thing.) Gilding comes as no surprise, on plush pillows, although Arlene Rush uses it air real fears of luxury goods and guns. In the same office, Caroline Voagen Nelson literally follows the money, in cash. What you will not find so easily are artists. In a "curator-driven fair," labels leave it to you to ask who made the work, and it may seem beside the point.

Does that put Spring Break at the opposite extreme from the uncurated artists at Clio and , later in the month, Superfine? Those two still cry out for quality control, but they only add to the good-natured chaos. "I cannot handle art with no artists anymore." So pleads Shalva Nikvashvili, in a painting for the dealer Why Not. She may have to wait a long time. Meanwhile, one can always have fun.

The independent century

Remember when the Armory Show had an entire pier for modern art? It was not all that long ago. Remember the days before such hoary institutions as the Frick, the Morgan Library, and the Met committed themselves to contemporary artists, not always in deep context? The past is alive and well where you might least suspect it,  the Independent. The fair I cherish for its classy but cutting-edge galleries takes a reassuring step back. Now held twice a year, it becomes for September the Independent 20th Century.

the Independent. The fair I cherish for its classy but cutting-edge galleries takes a reassuring step back. Now held twice a year, it becomes for September the Independent 20th Century.

Right off the entrance, it has a window onto that century with Mildred Thompson and her Window Paintings (with Galerie Lelong), with crazy loose verticals. Alice Baber (with Luxembourg & Co.) is just as hungry for abstraction with the stains of her Color Hunger, as is Norman Zammitt (with Karma) in glowing horizontals. Regina Bogat (with Zürcher) mixes things up in shaped canvas and the relief elements of wood strips and coiled blue cord. As here, many are unfamiliar, and many (no coincidence) are women. You can safely ignore Alexander Calder and Pablo Picasso (with Perrotin) or commissioned portraits by Andy Warhol (with Vito Schnabel), although experiments in photography by Sigmar Polke (with Sies + Höke) may come as a surprise. There too much is more to know.

This really was an independent century—and a diverse one. As Dat So La Lee, Louisa Keyser (with Donald Ellis) drew on Native American tradition for her baskets, while others bring folk styles to modern life, like Dindga McCannon (with Fridman) and Winfred Rembert (with James Barron) in Harlem. Ceramic busts by Myrtle Williams (with Salon 94) shine boldly and in black. Marie Laurencin (with Nahmad Contemporary), who exhibited at the original Armory Show, could sum up an alternative history of the century all by herself. I may have my doubts about Jack Youngerman (with Hervé Bize), but he did have his studio on South Street, just a few blocks north by the former seaport, like Agnes Martin and Ellsworth Kelly. You may have your doubts about Modernism itself, but come spring the fair will be back in Tribeca and in the present.

Art has no shortage of works on paper. Museums and galleries alike present them as a window onto the artist's thoughts or a display of the artist's hand. So why is Art on Paper once again the bargain basement of the fairs? That is not altogether bad, and it draws crowds all the way to the East River piers to shop around. Like many a bargain, too, it makes up for what it loses in surprise with the reliable and familiar. It is a lost opportunity all the same.

Could that be why top galleries stand out with the scale of painting? Could that, too, be why the fair itself backs away more and more from prints and drawings (apart from serial prints) to their seeming antithesis, sculpture and installation? It has risen to nine special projects, in the café, the aisles, and even a booth. There the artist displays not just his attachment to handmade or recycled paper, but to selling t-shirts. Another likes Modernism and its welded sculpture so much that he does a fair imitation, in painted cardboard. (If I seem to be avoiding names, consider it a favor to you and the artists.)

Caryn Martin has discovered that massed monoprints hung loosely enough have the look of plaster in progress. Billy Dufala and Striped Canary (aka Stephen B. Hguyen and Wade Kavanaugh) use plain paper to deliver a cube right out of Minimalism, in white, and an unruly tarp in yellow on the floor. They look impressive at that. Still, in the artist's book, drawing itself becomes the art object, yet the closest the fair comes is the bookstore. The most cutting project of all, by Tariqa Waters, peddling everything from a freed man's (or Freedmans) funeral to a naked girl on the roof of a car, takes the shape of yard signs. The yard sale is on.

What is left to ask?

Does New York need another art fair—a photography fair at that? Each spring, the AIPAD Photography Show already makes a case for photography as art. Work there falls safely within the bounds of fashion photography and the perfect moment, while the subjects of documentary photography all but beg for admiration and sympathy. Photofairs New York means to change that. The frankness of Robert Frank, the irony of Lee Friedlander, the detachment of Stephen Shore, the shock of Robert Mapplethorpe or Peter Hujar, and the intimacy of women among women still seem worlds away. In their place, though, comes a broader and less settled view.

Taken together and aisles apart, Howard Greenberg and Robert Mann galleries pull off a respectable survey of photography, as one should expect. After that, better think again. At the other end of the Javits Center from the Armory Show, Photofairs invites galleries not devoted to the medium, and the disjunction helps. Rodrigo Valenzuela (with Asya Geisberg) creates a landscape from studio debris, while HackelBury London displays artists associated with anything but photography, the Starn Twins. Media strain, too, to fit the formula, like video from Huntrezz (with Transfer).  As you walk by, you see yourself, but with additions that you may not recognize as yours—just as she hopes to escape conventions regarding private and social identity.

As you walk by, you see yourself, but with additions that you may not recognize as yours—just as she hopes to escape conventions regarding private and social identity.

ClampArt, too, can be counted on for gender bending, while shoppers for Catherine DeLattre (with Osmos) could almost be faking theirs. More generally, if the fair has a heart, it lies in a contemporary surrealism, with surreal lighting to match. Ole Marius Joergensen (with Momentum) takes one into Miami at night, while Amanda Means (with JHB) photographs the lighting itself. The approach can allow portraiture to acknowledge the viewer's gaze and to look back, like that of Kristine Potter (with Sasha Wolf). Subjects for Merik Goma (with Management) may instead look away, through the darkness and into the light. As a title puts it, Your Absence Is My Monument, but your presence is everywhere.

What is left to say or to ask about the Armory Show? Who will exhibit? Pretty much everyone, now that some dealers feel obliged to show both here and at an alternative fair, and that has me worried. What artists will they bring with them, and how will they look in a convention center? Again, pretty much everyone, in booths that offer more space than many a gallery. And not just younger galleries with their own section of the fair.

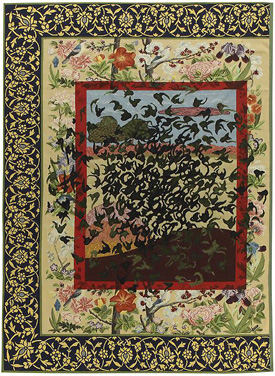

Can any artist stand out these days, or must you pick your own winners, if you dare? A section for solo artists makes, if anything, the least impact. What, then, for this year's theme? A section for material histories sure sounds in line with today's revival of thread, ceramics, and craft—and a layering of clay on fabric by Remy Jungerman (with Fridman), from Suriname, makes its heritage and its flatness palpable. Still, any and all work has its media, and the theme can excuse anything. It left me glad to retreat to the fair's long central island with its comfortable seats, a champagne lounge, and a dozen sculptures and installations.

Yet they, too, play to collectors and the crowd. Shahzia Sikander and Yinka Syonibare have their earthly godesses, Xu Zhen his cross between the Greek god of victory and the Buddhist protector of lost souls. Hank Willis Thomas has his silvery striker and Pae White the softer shine of her curtains. I preferred the closeness to death of Agnes Denes in her nineties, with skeletons in the acid pink of an airless glass box. What then is left to say about the fairs—or the business side of art? Return to the galleries and wait until next year.

These New York art fairs ran mostly September 7–10, 2023. Related reviews report on past years, the May art fairs just this past spring including Frieze, Frieze online, Art New York, and NADA, claims for the death of art fairs after Covid-19, and a panel discussion of "Art Fairs: An Irresistible Force?"