Reading the Fine Print

John Haberin New York City

Amy Wilson

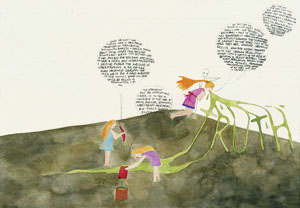

Amy Wilson does not make art for the farsighted. Never mind her thousands of words, in small, tight, hand-drawn capital letters, or the dozens of little girls and sometimes skeletons that populate her world. I started to estimate their number, extrapolating from a brief count to the eighty works on display in one show. At some point, I simply gave up. She means them to be too much for anyone to absorb, and

Over five years, Wilson's subjects have ranged from international politics to modern art to personal history, but each time placing the artist and viewer in a larger community. The words may derive from others or from her, but either way they let one imagine or puzzle over her personal history—and one's own. the delightful excess makes for some delightful art.

It takes a village

It has also made Amy Wilson a figure of controversy. A tabloid searched high and low through past exhibitions of the Drawing Center, looking for a good story. In particular, it was looking for a story juicy enough to derail plans for the Center's move to Ground Zero, as part of a larger cultural complex. The Daily News had to work hard, but in due course it latched onto Wilson—or rather onto a single image out of an ambitious drawing spanning several sheets. Again I do not dare estimate its word count. When it comes to images of war in Iraq, one can see why those girls and skeletons might have a lot to say.

One day, when the papers wish to denounce me, I only hope that they spell my name right—and direct others to this Web site. And when one broaches politics, one has entered a divided and divisive arena. Artists expect that, but attention can still sting. Fortunately, it can also trigger new associations and new art.

After a spring 2005 solo exhibition that found the art itself at the center of politics, Wilson returned in summer 2006 as part of a group show, "CHOPLOGIC." She could have made the controversy itself part of her work. Instead, among three artists all using text and all alluding to politics, she chose to avoid overt protest. Her characters enter the modern art museum, where they wonder at the very possibility of making art. Two years later with "The Myth of Loneliness," they delve into still more private spaces and a different kind of global village. And in 2010, a mural brings them teasingly close to Ground Zero after all.

While this review visits all those communities, a related article delves further into Wilson's role in the Drawing Center controversy. Two other articles describe an exhibition on art making the headlines, which included a panel discussion at which I presented along with the artist. I first saw drawing by Wilson in a group show at P.S. 1, where writers often mentioned her in the same breath as Amy Cutler, another artist who works on paper with plenty of white space, spare outlines, and a cast of young women in allusively rural settings. Art and feminism, it appeared, were not out of the woods yet.

But never mind all that. In Wilson's 2005 solo exhibition, only the farsighted reader, in quite another sense, could decide what she has culled from conspiracy theorists on the Web and what from more or less legitimate magazines. Potential buyers really had better read the fine print. If you do not know when to stop reading and when to look, when to join the treasure hunt and when to laugh, you may find that it becomes a chronicle of your present, too.

Only someone with remarkable assurance, too, could say what comes originally from the left or the right, what amounts to reportage or prophecy. Without question, they have all entered her imagination. Somehow they sound consistently, or at least collectively, like a reasonable, liberal critique of the Bush administration. They sound, in fact, rather like me and my friends after a few drinks. Perhaps one no longer can say something sufficiently outlandish not to engage real-world anger and despair.

Oh, that Abu Ghraib

The exhibition came at a time when many other artists were engaging those as well. A spring 2005 survey of political art would surely have to include Emily Jacir and Guy Richards Smit, to name just two. It could include as well so much art as text. Again, I originally saw Wilson's work, too, in context of dozens and dozens of other artists, at "Greater New York 2005." Why, then, are these little blonds having so much fun?

Wilson obviously exploits and actively disappoints the habits of a reader—or at least a reader used to political cartoons and how to take them in. She rides on the wave of "graphic novels" and the acceptance of alternative comics as art. No doubt she herself has contributed to that acceptance. She also belongs to a renewal of interest in imagery, fantasy, and outsider art. Her cast of characters and their landscape pay their debt to Henry Darger. Her rural world of grass, boat, and trees shares his curious mix of a mockery of innocence and a picture of hope.

Somehow, critics in the mass media have seen only a kind of humorless political cartoon, and so she became an excuse to deny art's place at Ground Zero in an International Freedom Center, in the shadow of buildings by Santiago Calatrava and Daniel Libeskind. I find it hard, however, to pigeonhole a voice this innocent and this crazed. Like Smit, she happily sees two sides to every story, but only provided the extremes grow fantastic enough. It helps a great deal to see her in so large a solo show. It becomes harder to write her off as nostalgic for nature or for a purer engagement with art. On Wilson's intense scale, any sense of a plain message quickly slips away. So does my confidence in my own cynicism.

Spaced out on gallery walls, too, the works look smaller and the execution more delicate. I could start to appreciate the watercolor, graphite, and white space as sunshine. The twenty acrylics began to convey a darker light. Darger exploits a mural scale to lock his manic energy, not to mention hints of adolescent sex or a battle between darkness and light, into a kind of Neoclassical reserve. Wilson's thin figures move more lightly or find themselves unable to reach for balance. I could never swear when the girls and skeletons are colluding—or at war.

Is her cast more hopeful, more rueful, and also funnier and more ironic than I had any right to expect? They also grow more familiar and intensely realized as one spends more time with them. I could almost take at face value the exhibition's title, "The Global Appeal of Liberty." I could almost believe it when the texts on freedom of thought burst into larger words, like fireworks in the air. Does a word like "Assassin" or "Regret" stand as a threat or a promise? I told you to keep listening.

Wilson still populates her drawings with blond little girls, and I no longer dare call them figures out of Darger rather than fully her own. However, they now take museums and galleries as their landscape, with enough personal favorites in the background—from at least J. A. D. Ingres to Dana Schutz—that no one can say she cannot make a painting. In one drawing, the girls camp out, and I kept worrying that Modernism's stalwarts would catch fire. In another, they hold a birthday party, and the paintings piled up and wrapped in bows might also find themselves mistaken for a trash heap. The texts seem to express uncertainty about celebrity, the redemptive power of art, and more than enough else to make one wonder where an artist's diary ends and quotation begins.

Art with a capital A

"If I wanted to send a message, I would have hired Western Union." Bob Dylan did not invent the line back in 1965, when he disclaimed the label of protest singer, but it still resonates. True, nowadays he might have found an Internet service provider instead, and yet the association of block capitals with politics and urgency lingers on. Think of what email etiquette calls shouting, or pull out a dollar bill. With "CHOPLOGIC," a 2006 group show, the title alone has me wanting less to parse the fine points of reasoning than to shout back. It also lets Wilson take her tiny letters and childlike characters out of headlines and into the modern art museum.

For one source of pronouncements, one can look to billboards and protest signs, like the angry scrawls of Raymond Pettibon, and Anthony Campuzano's paintings, which shared the gallery with her, resemble slightly dismembered ones. Sometimes he roughly centers the fields of text, and sometimes he crushes the words together near the bottom, like a trash bin after the demonstration. The appearance of collage extends to the ragged, distinct handling of each letter, as in a ransom note. I only wish that the messages or the thick, dark colors suggested more. I kept thinking that I missed the joke.

Down the hall, Melissa Brown manages just one joke, but a very good joke indeed. Perhaps I should say two jokes, since her smaller drawings of paper money fold in on themselves, each to reveal a second image. Regrettably, one obtains a fanciful landscape rather than Alfred E. Neuman. Her far larger works have the good sense to stick to her theme and to play it for all it is worth. They have images on both sides continued right to the edge, like true paper money, and their soft colors echo the shading recently added to foil counterfeiters. Even their scale pays homage to the U.S. treasury, which puts images the exact size of American money under suspicion of criminal intent.

Actually, Brown herself indulges in an elegant lowercase. Perhaps Old Europe if not U.S. currency will wish to adapt her font. Her letters spell out sometimes reassuring, sometimes more pointed clichés, like a self-help book for the American dream. Given the trade deficit and the cost of Iraq, the country might appreciate the advice. President Bush and his associates might thank her, too, for their prominent place on, appropriately enough, pretend money. Then again, I doubt it, especially as their likenesses indeed do remind me of Mad magazine, and at this rate future generations will end up with little more than play money.

It may take a moment to remember that Modernism has a long history of text as art and art as text, not necessarily with overt political intent. Within Dada and its associated movements, for example, only the circle in Berlin, including George Grosz and John Heartfield, rose consistently to anger. Ironically, at Bellwether, the one artist who has run afoul of censorship is immersing herself this time in painting and sculpture. Of course, I again mean Wilson, who does hand-letter painstakingly in capitals. She may be invoking art-world politics—or simply the trepidation that comes with making and viewing art.

Pop-up tarts

"The Myth of Loneliness" may sound like Pollyanna, but in 2008 Wilson found new friends. She has a new gallery, and she has made friends, too, with her own hands. The little girls in pencil and watercolor have put aside their skeletal alter egos, and the natural blonds in light dresses have joined a larger, more colorful cast. Their settings, too, have many colors. Besides the woods and landscapes devoid of vegetation, they escape into entire communities, if not exactly in perspective, at least with vertical layers that can fill the paper. Some of the warmest lighting comes where one might least expect it—atop a starlit tent canopy, in interiors, or scuba diving.

A village has sprung up in the center of the gallery, too. Tabletop railroad tracks wind through paper trees, houses, and factories. Airplanes and birds hang by clear threads from the ceiling. Bare trees on a much larger scale tower over the rest for good measure, while the birds continue into a second room. Wilson had envisioned a pop-up book, but even as paper constructions they suggest that Henry Darger has given way to a children's classic of her own devising. Her shift from works covering several large, horizontal sheets for many smaller drawings also suggests both a book and the gallery as natural environment.

A village has sprung up in the center of the gallery, too. Tabletop railroad tracks wind through paper trees, houses, and factories. Airplanes and birds hang by clear threads from the ceiling. Bare trees on a much larger scale tower over the rest for good measure, while the birds continue into a second room. Wilson had envisioned a pop-up book, but even as paper constructions they suggest that Henry Darger has given way to a children's classic of her own devising. Her shift from works covering several large, horizontal sheets for many smaller drawings also suggests both a book and the gallery as natural environment.

Of course, the book contains words, lots of them, in full capitals, in speech or thought balloons. At the Jersey City Museum in late spring, she cautioned that her drawings had more text than before. One had to smile, since all her shows feel a bit like speed-reading War and Peace without a Napoleonic complex. The Daily News hardly had the literacy, not back when it singled out just one figure from five long sheets at the Drawing Center—and all to damn the artist as a critic of a bad war and to censor art planned for Ground Zero. However, the scale is an important part of the experience. It makes one imagine a single narrative that one can never quite put together, and it encourages one to read a bit here and a bit there, for moments of happiness, memory, anxiety, and discovery.

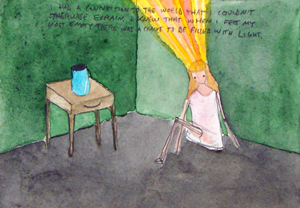

The moments are hers as well—a first kiss with her future husband, the realization that she could make art, the sense of a world outside her window, the release in learning that the imagination can help to fill it. When she shifted from found quotes for and against war to her own words, I wondered if she was in some way accepting responsibility—not so much for politics, but for her art and for herself. Those themes appeared to run through the series in Jersey City. Like the exhibition title, the new text may seem cheerier still. The little girls themselves take decisive action and find creature comforts, in autumn leaves and even in the rain. They swim the water, nestle in tunnels, and chop down a tree, perhaps to help the artist get over her stage of forest drawings.

I like happy endings as much as the next person, but I could take an exhibition title like this personally. Do not gag too fast, though. Should one see Prozac, perplexity, or irony? The undersea world could mean confinement, the tunnels escapism, and the fallen tree an aggression against nature—and a disturbing counterpart to an emotional breakthrough. The tabletop village has few signs of home, at least one of the airplanes has ended up on the ground where it does not belong, and I crashed briefly into a bird while reading the text. A model railroad can evoke child's play or an unhealthy adult obsession.

Perhaps one should feel in oneself a little of both, and grounded has double meanings anyway. The text, especially toward the end, describes an isolated, painful childhood, with a terrifying realm outdoors and a near certainty that art is too difficult—broken only by the discovery that these days anything can be art. One cannot say for sure when the terror ended, especially with so many epiphanies from which to choose. Freud might have something to say about the repetition. All those words and images should put critics in their place, and I do not pretend to have understood. I can still imagine real children playing here, and I can imagine many other starting points in these drawings, for next time and for others.

To make our garden grow

Lastly, for 2010 Wilson is thinking aloud in public again. For a few years now, her little girls have populated imaginary landscapes, brushed in after the figures. She has taken them from big watercolors to artist books, and their thoughts have become more intimate as well. Now she is working a public scale.

Her thoughts blossomed in January into a mural for West Thames Park. It hung there as the park by the Hudson grew and recovered, along with the rest of Lower Manhattan after 9/11. Thanks to the miracle of digital color printing, it stood five feet high and one-hundred thirty feet long. Yet the drawings, too, feel large this time. As usual, she works on long narrow sheets, which turn three walls into a single gently rolling landscape and a slowly unfolding narrative. So do the girls, in their words and actions.

Thinking aloud has got Wilson into trouble before, and so have public spaces. A tabloid seized on a single tiny figure from a dozen large, lush, and very private drawings contemplating the war in Iraq. Somehow it came to stand for anti-American sentiment in art, and it killed plans for that cultural center at Ground Zero, with the Drawing Center as its anchor. In no time Wilson's tiny capital letters turned away from politics, seeking a space apart to live, breathe, and create. Like Candide, she survived both trauma and hope for a better world. As Voltaire says at the end, she could cultivate her own garden.

In drawings for the mural, she does just that. The girls carry soil, plant seeds, and find pleasure and surprise in what comes out. So did the artist, she explains, in Jersey City, and the long, narrow sheets become a diary or chronicle. As if to insist on personal limits as well as adapt to the outdoors, the mural drops the thought balloons. It must have looked ramshackle enough on a temporary fence, and it unexpectedly came down before the show opened, so that its material now survives (seriously) only as handmade shopping bags. This is definitely not the best of all possible worlds.

Political it was, though. Since I first saw Wilson among emerging artists at P.S. 1, I was aware of the slippage between public and private events—a fact that makes art viable and political art so often controversial. The girls, mostly blond, are at once the grown-up red-haired artist, her memories, an idealized version of herself, and anonymous alternatives. They second guess themselves and each other. The show opened on Earth Day, and the text addresses the fate of the earth without losing its sense of humor. It also takes seriously the metaphor of cultivating a place for art.

Here, too, between subject and metaphor, the boundaries get slippery. The landscape and labor speak of home, while the text speaks of uncertainty. It loses patience with claims that a recession will help struggling artists by cleaning out extravagance, but it refuses to blame artists for struggling. As the work's title says, It Takes Time to Turn a Space Around. I had to relish a mural only blocks from where the Drawing Center might have stood, especially now that the public hates Bush's war, and I had to notice the hole there, too. What, the drawings have me asking, would a cultural center mean now in a culture without a center?

Amy Wilson's "The Global Appeal of Liberty" ran at Bellwether through May 19, 2005, "CHOPLOGIC" through August 11, 2006. "The Myth of Loneliness" ran at BravinLee Programs through October 18, 2008, "Please Pay Attention Please" at the Jersey City Museum through June 15. "It Takes Time to Turn a Space Around" ran at BravinLee Programs through June 5, 2010.