A Bit of Eden

John Haberin New York City

Carleton Watkins and Annie Leibovitz

Credit Carleton Watkins with a remarkable achievement: he "helped advance the notion" of Yosemite as "a Pacific paradise, a bit of Eden in North America." And then credit Annie Leibovitz for a pilgrimage in search of paradise.

At the time of the Civil War, Watkins translated the sheer scope of America into photography, just when others were doing the same in painting. Working today, Leibovitz has sought more intimate connection with great naturalists and photographers from America's past. Each acts as a map maker as well as an artist, even as the latter credits others with the map.  Now two museums seek to put them both on the map of photography. You may still remember Leibovitz first from her commercial journalism, because she brings much the same culture of celebrity to the medium and the past. She and Watkins share, though, a felt sense of landscape as history.

Now two museums seek to put them both on the map of photography. You may still remember Leibovitz first from her commercial journalism, because she brings much the same culture of celebrity to the medium and the past. She and Watkins share, though, a felt sense of landscape as history.

An American in paradise

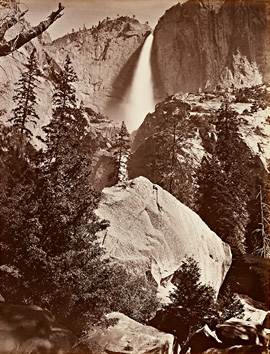

The Met credits Carleton Watkins with advancing a visionary notion of Yosemite, but even that sells him short. He helped make it so. Thirty-six photographs and two stereographs, most from the Stanford University libraries, help explain why. They show a land still untouched by tourists or developers. They offer a glimpse of Abraham Lincoln, turning aside from the burdens of war to imagine America's future and a more lasting Eden. They also call fresh attention to the role of the still-new medium.

Watkins certainly helped make it so in art. His epic sweep found favor with the Hudson River School, which did so much provide an image of America as a light among nations in a fallen world. Albert Bierstadt saw his work in a New York gallery in 1862, praised him, and purchased a set of his views in 1867. Bierstadt painted perhaps his own grandest view of the American West, now in the Brooklyn Museum, in 1866, the year of the photographer's third trip to Yosemite. While Bierstadt was painting the Rockies, he had been inspired to visit Yosemite and to experiment with albumen silver prints and stereographs himself. His Looking Up the Yosemite Valley in oil followed the next year.

One can see many of the same hallmarks in both men. They provide an ample foreground, as an entry into the picture. It may have the mirrored surface of a lake or river. It has trees, dwarfed by the scene as a whole, to set the scale. They have the particularity of portraits, perhaps as stand-ins for the photographer himself. They lead the eye beyond to a cavernous space filled with light—and, at a greater distance, craggy heights.

Yet Watkins helped make it so in life as well. The New Yorker may have moved to California as early as 1849, at age twenty, settling in San Francisco—where he lost his studio to the 1906 earthquake, a decade before his death. He paid his first visit to Yosemite in 1861, and, notes Jeff L. Rosenheim as curator, the photos "established his reputation." They also came to the attention of President Lincoln. A paradise must be preserved or lost, and Lincoln signed a bill in 1864 seeing to its preservation as the first step toward what would become a system of national parks. When Watkins returned in 1865 and 1866, he was working on behalf of the California State Geological Survey.

That task points to his distinction from the Hudson River School, too. For painters like Bierstadt and Frederic Edwin Church, the land partook of the Romantic sublime, at once clear in its path for humanity into nature and larger than life. Watkins sees a wilderness that defies access, with large rocks in the middle distance, treacherous waters, or the sheer face of distant cliffs. And he takes as his subject a single landmark, such as Mirror Lake, the Half Dome, El Capitan, Cathedral Rocks, the Bridal Veil, a tree as old as human history, or a waterfall shrouded in mist—under clear skies without once an approaching storm. Only twice does he ascend to create a panorama, and only once does he look to compose "the best general view." Like a geological survey, he has to map out feature by feature what is there.

That ascent makes a heady reminder of the technical challenges, much as for Linnaeus Tripe in Asia. Watkins was carrying literally a ton of equipment, including glass plates and dangerous chemicals, in order to achieve what were then huge prints (18 by 22 inches) of painstaking clarity and pristine whites. On his first trip he had to tilt the lens to capture the scale in front of him, and on his return he had to lug an even clumsier camera more capable of dioramas. He needed it to advance the very notion of Yosemite. In the past, the Met has argued for painting as a response to a divided America and for Civil War photography as an unprecedented record of death and destruction. Thousands of miles from the front, Watkins was looking ahead to the recovery of a larger nation.

The Cover of Rolling Stone

Emily Dickinson never made the cover of Rolling Stone, but their loss. She could have posed in that fragile white dress that still seems to go with her fragile but feverish poetry. She could have reached for its white buttons to bare herself and her feelings, like a rock star. This is Rolling Stone we are imagining, and I hear that Dickinson's letters to someone still unknown were rather racy. Elvis Presley, of course, is a proper subject for the magazine and an accomplished poser, but even there it may have missed out. A profile might have included his 1957 Harley-Davidson Hydra Glide, but would it show a TV set with an alarming bullet hole from one of his guns—or a family burial ground, its overwrought tombs bathed in an electric blue light?

Annie Leibovitz knows Rolling Stone inside and out, but it may again be missing out. One knows her for the glibly stylish photographs that have defined its image, along with that of countless musicians. Yet she photographed as well that one surviving dress, that motorcycle, that shattered glass of a picture tube, and the graveyard in Presley's Meditation Garden, just beyond his swimming pool. All were part of her search for the defining figures of photography, the modern era, and America. Now the New-York Historical Society exhibits her "Pilgrimage"—really more than two years of pilgrimages starting in April 2009, from the American West to Freud's London. The more than eighty digital photos display a cunning beauty and an extraordinary devotion, but have they recovered her for art photography?

Not that they have to try, for this is a historical society, and Leibovitz approaches figures from science and history as one of their own. She photographed the couch that led Sigmund Freud to the interpretation of dreams, but also his obsessively organized library, with the several volumes of Havelock Ellis's Physiology of Sex. Charles Darwin might have preserved the bones and bodies of pigeons just the other day, and Thomas Jefferson might still be scrutinizing the varieties of beans for his garden. A compass from the Lewis and Clark expedition to the Pacific in 1804 might still be showing the way. Writers, artists, and musicians, too, appear almost as naturalists. Dickinson presses leaves to paper exactly like John Muir, Pete Seeger leaves behind not his banjo but his vegetable garden and toolshed, and Marion Anderson's concert gown stretches out like the wings of an enormous bird.

Not that they have to try, for this is a historical society, and Leibovitz approaches figures from science and history as one of their own. She photographed the couch that led Sigmund Freud to the interpretation of dreams, but also his obsessively organized library, with the several volumes of Havelock Ellis's Physiology of Sex. Charles Darwin might have preserved the bones and bodies of pigeons just the other day, and Thomas Jefferson might still be scrutinizing the varieties of beans for his garden. A compass from the Lewis and Clark expedition to the Pacific in 1804 might still be showing the way. Writers, artists, and musicians, too, appear almost as naturalists. Dickinson presses leaves to paper exactly like John Muir, Pete Seeger leaves behind not his banjo but his vegetable garden and toolshed, and Marion Anderson's concert gown stretches out like the wings of an enormous bird.

Still, this really is art—and not just because anything can be art, so long as the artist says so. And its greatest resource is the close-up, like that of the beans, the compass, the buttons on Dickinson's dress, or Freud's and Ralph Waldo Emerson's bookshelves. It allows Leibovitz to evoke the presence of the dead and, now and then, to surprise. She also has a gift for color, which brings out the texture of Eleanor Roosevelt's Indian bedspread, Annie Oakley's riding boots, and autumn leaves outside Virginia Woolf's country house. She relies on it to pay tribute to her own influences without the burden of competing with them. They run almost exclusively to landscape, including Georgia O'Keeffe and, in photography, Ansel Adams and Julia Margaret Cameron.

Here, too, naturalism blends into artistry. Cameron notably staged her portraits as Victorian theater, like the drama that Presley at Graceland cultivated every day. Studies by Daniel Chester French for the Lincoln Memorial sit alongside studies after classical sculpture, grouped with Abraham Lincoln's gloves and Matthew Brady photographs, but as repeated negatives. Yosemite and Mount Shasta for Carleton Watkins hang in Emerson's dining room. Andy Grundberg, the curator and one of the best writers on photography anywhere, milks the overlay by interspersing another kind of pilgrimage entirely. There Leibovitz takes on the quasi-official American landscape, including Old Faithful (kaboom!), massive boulders at Gettysburg, and Niagara Falls buried in mist.

They show how much she aspires to art photography—and how much she still surrenders to beautification and convention. For her, Dickinson's living room is ever so warm and cozy, not self-imposed isolation, and so is serious art. For her, too, Jefferson's garden was not the work of an Enlightenment systematizer, the architecture of Monticello a central part of the system, but the source of a single pod sliced open to the light. A pilgrimage requires a shrine, and she approaches common objects like sacrificial offerings. Leibovitz's destinations do include Spiral Jetty by the very prophet of entropy, Robert Smithson. Yet she finds it no longer rising and sinking into the Great Salt Lake, but rather caked in salt as receding waters give way once and for all to a pristine white.

Carleton Watkins ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through February 1, 2015, Annie Leibovitz at the New-York Historical Society through February 22. Both parts of this article first appeared in New York Photo Review.