Tuning Out the Spectacle

John Haberin New York City

Peter Schjeldahl and Edward Winkleman

Is art at the mercy of big money? Is New York? Yes and no, and now a leading critic and an influential blogger and dealer look at the tangle of art, money, and spectacle. A related article, on another critic and plans for Manhattan's west side, extends the tangle to real estate. Several others cited here take up pandering, pressures, and a sell-out at MoMA.

In an exchange in print and online, Peter Schjeldahl and Edward Winkleman raise tough questions—and their answers are as different as yes and no. Does it seem strange to say no, even in the all too brief summer weeks when no one is hustling from opening to opening and from art fair to art fair? Does it seem stranger than ever when auction prices have reached $179 million for a late Picasso?  (Even my stepfather, who does not follow art news, had to forward me the headline.) It must seem stranger still coming from Schjeldahl, a critic who cares so deeply about art and the words to describe it. Yet artists who resent his answer may be missing something, too.

(Even my stepfather, who does not follow art news, had to forward me the headline.) It must seem stranger still coming from Schjeldahl, a critic who cares so deeply about art and the words to describe it. Yet artists who resent his answer may be missing something, too.

Money isn't everything

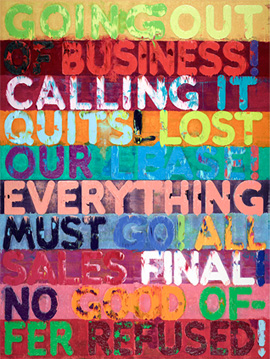

Peter Schjeldahl has pounced more than once on art-world excess, like MoMA's "Forever Now." Writing for The New Yorker, he has assailed much art of the present as shamelessly recycling the past, in what he calls "Neo-Mannerism." Yet he is also far from conservative critics like the late Robert Hughes who dismiss art since Andy Warhol as an exercise in cynicism. Schjeldahl has a talent for tuning out the noise of opening after opening, to immerse himself in museums—and he asks that you do the same. "The gross spectacle and deep-down sameness of proliferating art fairs, produced for the convenience of jet-set collectors," he writes, "dismay only if you take them seriously as something other than silly-time circuses." Besides, he adds, you can always slip off to the Frick.

That zone of comfort has earned him a sharp rejoinder from someone who would bravely and clearly answer yes. Edward Winkleman, a dealer who has hosted devastating maps of excess by William Powhida and Ben Davis, sees Schjeldahl as surrendering to power (where I omit ellipses in excerpting in order to preserve his):

To expect the running-scared super-rich to behave benevolently, in regards to art, is plainly foolish. Worse, it would rob us of the occasional pleasant surprise. As unimportant as he suggests the excess of money sloshing about in the art market is, he still devoted an entire article to it . . . in "The New Yorker." I prefer to believe some degree of Diogenean reservation and protestation still matters and is still worth enduring the contempt of the more cynical (in the contemporary sense of the word) critics of such actions.

No doubt Winkleman, author of a book on how to succeed as a dealer, has his own moments of optimism and outreach. How could he keep going otherwise? Elsewhere he suggests, perhaps a little too conveniently, that better art fairs could help relieve the financial pressure on artists and dealers. In response to the corrupting influence of art advisors, he argues that dealers can and should screen out "flippers"—collectors with nothing in mind but quick profits. His blog post, "A Critique of Schjeldahlian Reason," plays on Critique of Cynical Reason, Peter Sloterdijk's criticism of "enlightened false consciousness." When I pointed out that Kant's Critique of Pure Reason hardly dismisses reason, he agreed and called his title "clickbait."

Could Schjeldahl and Winkleman both be right about big money in art, and can I owe a debt to them both, in a subject this Web site has explored again and again? To answer yes and no, one had better take both answers seriously. No, because there is not one art world but dozens, encompassing thousands of artists and hundreds of dealers. Sure, a few wealthy collectors may feel entitled to, or validated by, the few names they know, just as some seek a trophy wife without all men thereby becoming pimps and all women whores. Overlooked artists may go along with talk of celebrity and spectacle, too, to explain their own marginal status, but that only reinforces the prevailing cynicism. Both miss what matters most—the steady work of midlevel artists and dealers on behalf of themselves and others.

And yet the corrupting influence is real—and often overwhelming, just as with that late Picasso, painted decades after his greatest work and his greatest influence on modern art. Every leap in rents, prices, and competition drives some out and pressures still others to conform. One could see it in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, and one can see it again with every visit to the Lower East Side, where the gallery sprawl now tops one hundred. The course of empire matters to everyone, just as luxury towers in Chelsea bear on changing patterns of urban living and a shortage of affordable housing. No one is immune from conflict, not even those I admire. Think of Jerry Saltz, who bravely called out art's "battle for Babylon," but who mostly reviews, zealously, hot artists and has become something of a celebrity himself.

Art has an awkward place among the arts, between luxury good and mass entertainment. That status goes back to at least the Renaissance, with its petty warlords and new humanism, and they go together. What warlord would not care for manipulating his image and the public? There is no going back to art for an educated elite—and also no easy way to leave it behind. Now, though, art faces a simultaneous growth in both sides of the story, its prices and its popularity, with all the distorting incentives from both. All one can do is to bear the circumstances in mind when looking at art, to suffer gladly, and to speak honestly—and maybe, when the art world is too much with us, to head for the Frick.

The art of resentment

Artists, then, have always worked for money, at least since civilization defined art as a thing apart and coined money. Patrons and purchasers have elevated art and corrupted it, and no history of art would be complete without asking how. The artist driven only by an inner demon is an entirely modern ideal—and, to mix things up that much more, modernists also did their best to defy it. They appropriated fake wood grain and a very real urinal. They subordinated the Romantic imagination to formalism. In today's overheated market, charges of corruption are understandable and well founded. Yet they carry with them far less justifiable fears and resentment.

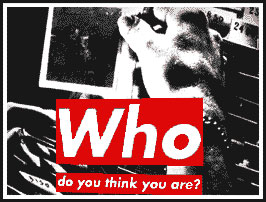

They also run up against some nasty paradoxes. Artists often complain that "theory" cast aside painting and sculpture. Yet theory was itself a critique of art institutions, wealth included, and so was a generation of artists. Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer look as savage and chastening as ever—while another kind of feminism, in the early work of Cindy Sherman and Laurie Simmons, has taken on with time an unexpected tenderness.  Besides, theory's heyday ended some time ago now, before a resurgence both of painting and, alas, money. Art could do these days with more criticism dedicated to insight rather than promotion and the art of making money.

Besides, theory's heyday ended some time ago now, before a resurgence both of painting and, alas, money. Art could do these days with more criticism dedicated to insight rather than promotion and the art of making money.

Conversely, David Hockney, the artist best known for lamenting the death of art, is a paradox all to himself. The man so worried for painting has argued, I think wrongly, that Jan Vermeer relied on mechanical means for what you and I mistake as magic. To detractors, Hockney is also, ironically, the British equivalent of Andy Warhol—but without the constant experiments, the generosity to others, Warhol's religion, and the looming presence of death. That leaves only glibness standing in the way of talent. Then, too, if Warhol had his Jean-Michel Basquiat, Hockney has his own street artist under his mantle, Ramiro Gomez. Lawrence Weschler in The New York Times praised him for it just this August.

Many artists who feel excluded by money and spectacle have their paradoxes, too. They may wish others would talk less and look more, but then they often turn to artist collectives that are anything but discriminating. Their big group shows, hung Salon style, mirror the excess of the art fairs. They make distinct work blend together, they wrench individuals from a body of work and a context, and they all but prohibit taking the time to discover and to appreciate their art. Come to think of it, the actual French Salon in the nineteenth century did not do much for painting either. Group shows and collectives have their place, to give voice to many and to add to the delights of summer sculpture, but there is only so much good that they can do.

Artists and the public alike imagine secret dealings and insincerities that just plain do not exist, and there, too, lies a paradox or two. On the one hand, even someone like Jeff Koons takes his art seriously, not least when he is joking. He surely thinks of himself as reaching out to a broader public while taking aim at exclusive institutions. He is pandering and shallow, but by no means cynical. Neither are dealers who invest in "museum quality" shows with almost nothing for sale, like Gagosian's twin 2015 exhibitions of artist views of their studios. No doubt it is a good gamble, increasing prices in the long run, but it is not a gamble that anyone would take without a dedication to art.

On the other hand, they could happily turn the tables on me and my friends fed up with installations and celebrity. The mass of painting and sculpture out there includes plenty of forgettable retreads of the past. What if we are the ones following an art-world formula? Maybe not, at least not all the time, but there is no simple distinction between good guys and bad—and no excuse for resentment. Long ago, Friedrich Nietzsche described ressentiment as a wallowing in self-pity and pity, and neither is warranted. And again, all one can do now is to speak out against the madness and to make the best art one can.

Peter Schjeldahl wrote for The New Yorker on July 13, 2015, and Edward Winkleman replied in his blog. And do not forget the 2016 art fairs coming up.