Between Courtly and Renaissance

John Haberin New York City

The Limbourg Brothers: The Belles Heures

Pages of Gold and El Greco in Crete

The Limbourg brothers make unlikely candidates for avant-garde artists. Like proper craftsmen, Herman, Paul (or Pol), and Jean (or Johan) began work as teenagers, and at least two trained in Paris as goldsmiths. They worked so closely together that, even today, one cannot tell their hands apart. They died in 1416, the oldest barely thirty, without completing their masterpiece.

Yet they worked at the dawn of a century, and they helped the Northern Renaissance come to be. In "The Art of Illumination" at the Met, one can watch it come into being, while still seeing much of what it left behind.  Was the Renaissance, then, literally a sudden rebirth—and the model for every art movement ever since? Or was it a product of the workshop system and a gradual unfolding? Maybe both, and "Pages of Gold" at the Morgan Library shows how long illuminated manuscripts clung to the past.

Was the Renaissance, then, literally a sudden rebirth—and the model for every art movement ever since? Or was it a product of the workshop system and a gradual unfolding? Maybe both, and "Pages of Gold" at the Morgan Library shows how long illuminated manuscripts clung to the past.

On an island close to Europe and a world away, the Renaissance naturally took a little longer. By the time it strikes home, in fact, El Greco has already taken it somewhere else. "Icon Painting in Venetian Crete" looks for El Greco's roots before his arrival in Italy.

Band of brothers

The Limbourg brothers were not the first around 1400 to break with the courtly International Style. A panel painter in Dijon had pulled off a monumental realism they never knew. They were also not the last to create the Renaissance on paper. Jan van Eyck and his brother Hubert van Eyck may have illuminated manuscripts, and people still argue over who did what and when. However, the Limbourg brothers worked a generation before van Eyck. In fact, their virtue lies in their place between old and new, and the Belles Heures de Jean, Duc de Berry is a transitional work for them as well.

The manuscript has more than four hundred pages, and the Met has unbound more than a hundred. (If it seems out of order at times, I read the folded Sunday book review each week from the "outside in" myself.) They started on it by 1405, when the duke was well into his sixties, and they finished it before 1410. Robert Campin's Mérode Altarpiece, a bombshell in painting also in the Cloisters, lay a good fifteen years away. The Hours of Catherine of Cleves from the 1430s, at the Morgan Library, had more shocks, but nowhere near the influence.

Historians speak of the International Style with good reason. The duke's family alone, the Valois, stretched from Flanders to Philip the Bold in Burgundy. The brothers also knew manuscript illumination in Italy. It supplied a model for more fully modeled figures, bare hints of linear perspective, and flowers not found in France. Still, their floors tilt up irrationally, rooms can look as cramped as cages, and clothed figures gain much of their power in silhouette. These elements add at once decoration, a sense of realism, and divisions within a narrative—like the panels of a comic strip today.

The Book of Hours has all the International Style's elegance. Many figures tread lightly or on tiptoe, naked or with a nicely exposed leg, even when mashing grapes. Women are fashionably slim with fashionably large bellies. They bend gracefully for martyrdom, and the curved swords never descend, as in a stately dance. A calendar page may include a peasant killing a boar or feeding pigs, a well-dressed man warming himself by the fire, well-observed fish, bar charts for the hours of prayer, and dozens upon dozens of twining gold leaves. They function as not just the year in miniature, but a self-enclosed feudal world.

For all that, the delight and importance of "The Art of Illumination" is its inconsistency. Sure, psychology can be minimal, with hardly any suffering in the Agony in the Garden. Joseph is still the old-fashioned ancillary character, asleep at the Nativity. Yet Jesus squirms when his mother holds him on the flight to Egypt. The lives of saints are full of conflict and fantasy, from frightening skeletons to the grander architecture of Catherine's double wheel. Hills tend to provide a stage backdrop rather than a vista, but angels and distant towers may peep out from behind them.

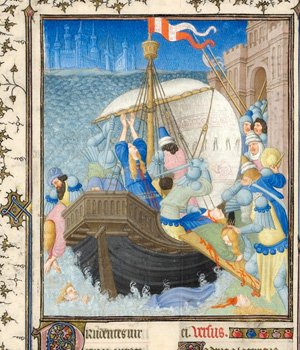

The brothers are above all painters and colorists. They typically single out the principle actor in rich blue against pale or earth colors, while light plays off the grass. They descend into grisaille, or shades of gray, to communicate the darkness before the Resurrection. They communicate feeling best through massed figures—a procession of hooded monks, a wild cluster of gravestones, or swords pointing every which way. Their unfinished masterpiece, the Très Riches Heures in Chantilly, will have deep snow-covered landscapes, walled cities, and the garden of Eden as a world to itself. However, that is another step in an unfolding tradition and a permanent revolution.

A Renaissance folk art

"Pages of Gold" come from all over Europe. In England figures have rigid, elongated poses that make them a record of piety, chivalry, rivalry, learning, and bloodshed. The few sheets from France come later—after painting in oil had taken the lead—but they recall how illuminated manuscript and its imperial splendor had contributed its soft colors, fluid washes, courtly actors, and deep landscape. And by 1500, Spain fully felt the impact of the Northern Renaissance. As Mary tends to Jesus, a worshipper defines the foreground. Another peeks suddenly from behind a curtain, much as a museum visitor catches a sudden glimpse from the opposite angle. van Eyck had made possible that mix of naturalism, magic, and reflection upon reflection decades before.

At least half the show, though, comes from just one country. It offers a concise account of the early Renaissance in Italy. In the past, the Met has called manuscript painting a "lost art"—and credited it with the origins of the Italian Renaissance. Here it appears instead as an undercurrent. It bubbled under the 1300s, keeping innovation after Giotto alive through thick in thin. In other words, it acts as both an elite private enclave and a true folk art.

The Morgan does not have to make extraordinary claims in order to boast. It can draw on more than five hundred pages alone from the Hungarian Anjou Legendary—painted in Bologna around 1330, very possibly for the Duke of Hungary. Then come the Decretal of Pope Gregory IX, also from the fourteenth century, and a Florentine Gradual. (The museum also owns Le Livre de la Chasse, from fifteenth-century Burgundy and displayed last year.) By the time these entered the collection, lack of understanding or sheer greed had dismembered them into separate sheets. Buyers and sellers of the Legendary also sliced away the text, leaving just images.

A "legendary" even sounds like a folk tale. It dwells on such extra-Biblical stories as Christ's harrowing of hell and Saint Bartholomew, the apostle who was flayed alive. It dwells on soldiers playing dice at the foot of the cross—and on plenty of weeping.  It also groups four crowded scenes on each page, two by two, like panels in a comic strip. The figures come to life from the very lack of parallels in side-by-side compositions. Landscape is notably absent. That accords with the growing conservatism of the century, which put authority figures first, but also with the narrative focus of a plain storyteller.

It also groups four crowded scenes on each page, two by two, like panels in a comic strip. The figures come to life from the very lack of parallels in side-by-side compositions. Landscape is notably absent. That accords with the growing conservatism of the century, which put authority figures first, but also with the narrative focus of a plain storyteller.

Text necessarily drives a Decretal. (Hint: think of a pope's decree.) Yet it also represents an advance in naturalism, and it keeps alive a sense of wonder in the years before sculpture by Lorenzo Ghiberti and others. In turn, the Gradual hints at painting in Florence finally kicking into gear. One can easily follow the story in either one, but its plots and subplots do not reveal themselves all at once. Space now fully surrounds the figures, and the figures themselves regard one another with wonder.

Just as the text guides the narrative, the artists make creative use of the page as text. The three wise men at page bottom, like a footnote, went their way to Jesus's birthplace in the capital letter. Flowers spring up everywhere in between. In a capital B, a row of angels in the top loop look attentively upon Abraham in the bottom. The letter O frames the Last Supper as itself a circle, and the action turns on Judas right in the foreground. As the sole person eating, ravenously and happily, he changes everything by his sin—but he also seems thoroughly, awfully human.

Islands in the stream

Once upon a time, a young artist came from a backwater to an urban center, drawn by cutting-edge painting. He brought with him sentimental habits, a volatile personality, and the potential to transform European painting. I mean Pablo Picasso, but the Onassis Cultural Center in midtown tells the very same story about the Renaissance. "The Origins of El Greco" tries to place a great artist within developments back home. Crete nestled between Greece and Byzantine art, but increasingly within the sphere of Italian city-states and Venice's sea trade. The show claims Crete as a meeting point of all those influences, with El Greco as the product of their collision.

The very first works, like a Madonna and Child from before 1400, have the frontal poses of an eastern religious icon, outlined in gold and a single color against gold leaf. Even so, they have a surprisingly large scale and freedom of movement in the child's regal gesture. Renaissance Florence in 1420 would have loved the theme of Saint George slaying the dragon, with his sharp diagonal thrust, or a tiny marzipan city nearby. Another Saint George already mixes gold leaf, Tuscan tempera, and Venetian color, but alongside a favorite Cretan saint named Merkourios—and together they tread on a villain in Ottoman dress. A Nativity retains the Gothic tradition of a cave rather than a manger, but fantastic figures spill over the cave mouth. By 1500, contrapposto is second nature, but with Gothic shadows and almond eyes.

Venetian color takes over the first consistently three-dimensional vista, highlighted by the foreground figures and their starkly black and white robes. Yet gold leaf will not go away without a fight. In fact, compositions grow more rigidly symmetrical than ever, with massed actors on two different scales. Crowding at the Crucifixion and exaggerated death throes may look back to Gothic models—or they may import new influences from the Northern Renaissance. Still, one artist copies the art of Giovanni Bellini in Venice right down to the Madonna's free turn to embrace Saint John. A favorite subject, Saint Francis, drops in from the Italian mainland, too.

Mannerism intrudes with the sixteenth-century, but even its heightened emotions build on Gothic models. In a small altarpiece for private devotion, sharp contrasts of black and color sort out the preposterous detail and cramped tiers at the Last Judgment. A magi's awe is indistinguishable from fear, and it relegates the birth of Jesus to a sidebar. A rearing horse shows the fullness of life and his owner's courtly command, but also the horse's cartoon smile. Michael Damaskenos, one of the few Cretan artists remembered by name, contributes a Last Supper. Its round table carries the eye gently past its center, in place of the usual drama of recoil and betrayal.

With El Greco at last, every century comes into play. The heightened bulk and drama of a man's back leans across a small, geometric tomb that Giotto might have painted way back at the birth of the Renaissance. Yet the diagonal action carries one's eye rapidly into the landscape, past tuft-like trees right out of Bellini and Titian. In the artist's very first surviving work, the death of the Virgin Mary, only a circle of funeral candles breaks the rigid and retro verticals. Eight years later, the electric blue light of El Greco the visionary fills the sky and unites intense subplots, with figures in rapt attention. By 1605, the cloak of God and Jesus sweeps up angels and Mary toward the Holy Spirit, with a clarity and unity that parallels the first years of Baroque.

The show defies tidy narratives about origins. Art often does. Even that last composition floats above an unknown ground and cuts off everyone's feet. Besides, with his first known work, from 1562, El Greco has already left Crete for Italy, on his way to painting in Toledo, Spain. (Okay, the Onassis Center has to cheat, but take what you can get.) Innovation takes both outsiders and traditions.

"The Art of Illumination: The Belles Heures de Jean, Duc de Berry" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through June 13, 2010, "Pages of Gold" at The Morgan Library through September 13, 2009, and "The Origins of El Greco: Icon Painting in Venetian Crete" at the Onassis Cultural Center through February 27, 2010.