How to Hate the City

John Haberin New York City

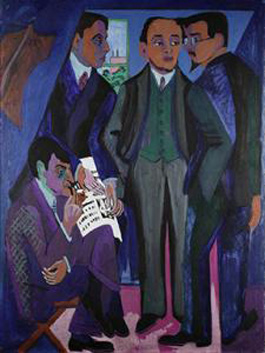

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

No movement in early modern art was as cosmopolitan as German Expressionism—and the group that called itself Die Brücke. Who else took to the streets, when Picasso was just finding his way from circus performers to still life? Who else first exhibited in a former butcher's shop, where it also met? When, decades later, Adolf Hitler denounced the movement as "degenerate art," his rhetoric feels familiar from religious conservatives even now blaming a perceived moral decline on urban liberals.

And who in Die Brücke was as cosmopolitan as its oldest founding member, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner? That butcher's shop in Dresden was his first studio, and he hit the streets all the more knowingly after his move to Berlin, the capital city.  Nothing of his sticks in memory so much as a scene from 1913, in which fashionably dressed men and women press forward without ever quite acknowledging one another's existence—except, perhaps, by competing for attention. One can feel a sidewalk as the site of congestion and isolation just as much today in New York. So why did he pass his last thirty years in the Swiss Alps? The Neue Galerie shows Kirchner's love-hate relationship with a city, its inhabitants, and himself.

Nothing of his sticks in memory so much as a scene from 1913, in which fashionably dressed men and women press forward without ever quite acknowledging one another's existence—except, perhaps, by competing for attention. One can feel a sidewalk as the site of congestion and isolation just as much today in New York. So why did he pass his last thirty years in the Swiss Alps? The Neue Galerie shows Kirchner's love-hate relationship with a city, its inhabitants, and himself.

The retrospective has a room each for his three locations, plus a smaller room for his military service and another room for prints. (An ample time line is worlds of help.) If you think of German Expressionism as a response to war, fascism, back-room deals, and starving garrets, it will remind you of how early and presciently it began. Still, wherever he went, Kirchner was never comfortable in his time and place. He could never fit into quite a different time line—of Modernism as a steady march to artistic freedom, the transformation of society, or, if you prefer, formalism. He is all the more searing for that.

The cosmopolitan

Modernism can still make news even now, but the news appears in Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Cubism mostly in fragments of newsprint. A textbook by John Russell calls one chapter "The Cosmopolitan Eye," but it starts with Wassily Kandinsky on the road to abstraction, before turning to Marc Chagall and his rural flights of fancy in Russia. Still others, like Surrealism, sought not the headlines, but an alternative reality in art—and Dada before it an alternative to reality and art. The Ash Can School and George Bellows lingered over New York's docks and tenements, but were they all that modern? Of course, this cheap history overlooks how cosmopolitan all these were—and how their realism turns on a city's cafés, theaters, transgressions, and hidden places. And so, too, did urban realism for Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

You may think of German Expressionism as more a deliberate distortion of reality than its acknowledgment. You may love it or fear it for its desire and revulsion at the sight of human flesh. Yet its moral or amoral fables make no sense apart from its concern for historical memory. Artists like Egon Schiele exposed themselves because they were putting themselves on the line. After World War I, Max Beckmann, George Grosz, and others confronted the misery of the Weimar Republic and its fall. As the Nazis bore down, they felt impending disaster on a street corner or at a factory—but no one felt it as early and as personally as Kirchner.

Born in 1880, he learned the rootlessness of cities the hard way, as his father kept moving in search of a living. He was born in Bavaria, but he grew up in Frankfurt and Chemnitz, and he studied architecture in Munich and Dresden. He was not the first German Expressionist, an honor better assigned to Gustave Klimt, but he was arguably its first modern artist—a year older than Picasso at that. He founded Die Brücke with Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff in 1905, and its members became a who's who of prewar German art, including Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein, and Otto Mueller. Its name means "the bridge," and they meant it as a bridge to the future. "Everyone who reproduces," Kirchner declared, "directly and without illusion, whatever he senses the urge to create, belongs to us."

That optimism was not to last, assuming it ever existed, and neither did Die Brücke. Kirchner did not often play well with others. His written account of the group in 1913 angered everyone, and it soon dissolved. Still, he sought that bridge to the new, starting on the margins of Dresden. He painted its intellect and its impulse, its dancers and its decadence. Picasso did much the same in Paris, at the circus and in the brothel of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.

Kirchner sought that bridge in recent art as well. His subjects recall Edgar Degas and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, but his street views, impasto, and acid colors look to Vincent van Gogh. Soon enough his fields of color become broader and thinner, as he caught up with Henri Matisse. He titles a painting in Berlin after a woman's green blouse, much as titles by Matisse call attention to a green stripe or a red coat. Still, not for him the French artist's "harmony in red"—or in anything else. Even in Berlin, where he moved in 1911, the bridge over a canal returns him once again to van Gogh.

He is ready at last for the street. In a loan from MoMA (which also has an equally fine street scene set in Dresden) and a more crowded version in the Neue Galerie collection itself, men and women do not so much descend the sidewalk as walk on water—or, rather, an alarming purple fluid that ascends the canvas. Their elegance and sexual charge continues in tall, narrow male portraits. Kirchner owes both compositions (as Russell points out) to Edvard Munch, but again, I might add, with that cosmopolitan difference. For Munch, the borders of a street or city place it on the edge of an infinite sea and a scream. Kirchner's Berlin is closing in, in the present, even as its inhabitants press on and extend its limits.

The theater of modern life

What happened on the way to the mountains—and to suicide in 1938, at age fifty-eight? The curators, Jill Lloyd and Janis Staggs, find the answer in World War I. Kirchner volunteered for military service and landed in the reserves. It kept him out of combat, but he suffered a breakdown all the same. Self-medication with alcohol and actual medication with no end of drugs only made things worse. He went to Davos, in Switzerland, for an exhibition of Ferdinand Hodler, the symbolist painter, but he stayed for a cure.

That story has its villain in war, but it plays down his complicity, as he knew well. A self-portrait in uniform has him dangerously yellow and gaunt, but still sneering and still with a cigarette in his mouth. In prints, he identifies with a soldier who sells his soul to the devil. He was ever the irascible that burnt his bridges and exploded the Bridge. The story overlooks, too, the complicity of his times in the years to come. The Nazis seized more than six hundred of his works in 1937, many of them right off museum walls, and exhibited two dozen in its show of "Degenerate Art"—and he took a gun to his head as the prospects of war and the German army were closing in.

The story overlooks as well his ambivalence about the city and the cosmopolitan all along. True, his escape to the edge of Dresden was an escape to the cutting edge, much like Montmartre for Picasso, but he had no love for the modern city or its historic buildings—like the great cathedral destroyed by allied bombing in World War II. He escaped the city center from the moment he arrived in Berlin, too, for enclosing forests and open skies. His paintings grow larger in Davos, where he sought comfort in peasant life, but not without the darkness. Night has the eerie glow of moonlight, but without a moon. He gives up painting altogether by 1925, in favor of tapestry, inactivity, and death.

That dream of escape corresponds to a larger ambivalence about modern life—an ambivalence shared by the entirety of German Expressionism. It shows even in Dresden, with his early sharp contrasts and thick brushwork. A male portrait approaches a side of beef twenty years later for Chaim Soutine, who would have appreciated a studio in a butcher's shop. Tightrope walkers seen from above seem to be walking unsteadily on the ground. Colors keep clashing, while dancers wear pink against a field of pink that refuses to match up. A woman at a dressing table looks ordinary enough, but her reflection in a titled mirror leaves everything awry.

In all these, he is attracted not just to theater, but to the theater of modern life. Kirchner sees everything as a morality tale without a clear moral, and it has him looking to connect not just to contemporary art, but also to the deep past. He cites as further influences Albrecht Dürer and Lucas Cranach in the Northern Renaissance. An older woman could correct the casual sexism of female portraiture, but as a death mask. Is he seeking a German essence quite as much as the Nazis, or is he just in perpetual despair? Maybe both, and maybe that ambivalence explains how often his early work entwines figures like mirror images.

His fascination with the past appears just as much in his choice of woodcuts when it comes to prints. Yet there, too, he is also modern. He adopts color woodcuts, so that multiple impressions fit together like jigsaw puzzles—and his color lithographs, although a single impression, have the same novelty. He was again on the cutting edge in 1913, when he exhibited in New York in the fabled Armory Show, and he had a solo show at the Detroit Institute of Arts two years before his death. His skin and his conscience may have been jaundiced, but he still had the cosmopolitan eye.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner ran at the Neue Galerie, through January 13, 2020. This review appeared in a slightly different form in Riot Material magazine.