Lessons in Blackness

John Haberin New York City

Isaac Julien on Frederick Douglass

Richmond Barthé and the Harlem Renaissance

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe

"My back is scarred by the lash—that I could show you. I would if I could make visible the wounds of this system upon my soul."

Frederick Douglass made the wounds of slavery visible for a generation of white Americans, starting before the system itself came to an end in the Civil War. Making visible is also the business of art, and Isaac Julien recreates an address by Douglass in all its eloquence, on "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" And what is it, Julien asks implicitly, to African Americans today?  The address provides the framework for an intimate look at the speaker's life as a free man, on video at MoMA. In the exhibition's title, it poses Lessons of the Hour. It asks, too, whether a divided nation can ever escape slavery's lessons.

The address provides the framework for an intimate look at the speaker's life as a free man, on video at MoMA. In the exhibition's title, it poses Lessons of the Hour. It asks, too, whether a divided nation can ever escape slavery's lessons.

This could be Julien's year. Douglass escaped slavery in at age twenty-one, in 1838, and Lessons of the Hour takes its title from a speech in 1894, a year before his death. Again on video, in the Whitney Biennial, Julien brings to life the Harlem Renaissance and its leading sculptor. He also curates an exhibition of that sculptor. There is nothing savage about the art of Richmond Barthé—and, if there were, he would be the first to tame it. If you have any doubts, head right for Feral Benga, in a gallery retrospective of a thoroughly sophisticated artist.

What, though, of the South they left behind? Has anything changed in forty-five years on Daufuskie Island? Will anything ever change? One can only wonder on coming to photographs of black Americans by Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe at the Whitney. She must be wondering herself. And yet she has left nothing behind but her anger.

His finest hour

"I have watched from the wharves," Douglass said, "the slave ships in the Basin, anchored from the shore, with its cargoes full of human flesh. . . . In the still darkness of midnight, I have been often aroused by the dead heavy footsteps, and the piteous cries of the chained gangs that passed our door." His words evoke pictures, and so does Isaac Julian, but less painful ones. He opens to trees, to a gentleman's study and a woman sewing, and to the man himself, slowly leading a horse. He follows Douglass on the train, looking inward and perhaps creating those words in his head. He ends with Douglass standing tall on a mountain's peak, like the statue of a hero.

He works in film, transferred to video, for the epic clarity of its color. It runs from day into night and from introspection to fireworks on, of course, the Fourth of July. It includes shots of an hourglass marking the hour, if not its lessons. Still, time and history have a way of playing tricks. Day breaks again after the fireworks, on its way to the mountain. The sands of time sometimes flow and sometimes stand still.

Julien hopes to encompass both reality and hope, especially when they collide. A hand picks cotton, but it might almost be picking white flowers for their beauty, with echoes soon after in yellow glistening on a tree. The audience for oratory files into a Methodist church with the bare architecture of an arena today. It includes blacks and whites, men and women—some in the fashion of the day, others in the present. Other clips borrow police surveillance tape of protests against police murder, although I somehow missed them. The video runs just under half an hour, but one can enter as one pleases and, in time, see the loop begin again.

I first encountered the artist, born in England, in London in 2003, already moving in and out of history. Two videos placed him both within a Trinidad community forty years earlier, after a poem by Derek Walcott, and a contemporary city much like Baltimore, where Douglass lived as well. When I caught up with Julien again, with Playtime in 2013, I worried that he fixed all too easily on his heroes and villains. (Do read my review then, for a fuller picture.) Has he finally found the hero he deserves? Has his hero found the response he deserves, in fireworks and, in church, applause?

As Douglass, Ray Fearon makes his character nuanced, steady, personal, and profound (and I wish that the museum took more care to credit him). Then again, I may have sold Julien short all along. Ten Thousand Waves, in 2010, already has many messages and many channels to mess them up. His latest video, a highlight of the 2024 Whitney Biennial, comes closer still to an installation and a hall of mirrors. It also moves easily in time, back to the Harlem Renaissance. Now MoMA presents Lessons of the Hour, first shown in 2019, as a historical document itself.

Douglass was the most photographed American of his time. And the curators, Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi with Erica DiBenedetto, set out photos, publications, and newspaper clippings, floor to ceiling and in cases. They also include the handwritten text of a speech on the role of images of black and white America. Is blackness once again "going dark," feared by or invisible to white eyes? For Julien, Douglass speaks forcefully but never gets over his introspection, his memories, and his pain. "Anything, no matter what, to get rid of thinking!"

Not the savage mind

What may sound feral in Richmond Barthé is a 1935 sculpture, with the skilled modeling of the School of Paris brought to New York. And what may sound like the sculptor's considered judgment, harsh or appreciative, of a wild man is the stage name of a cabaret dancer. He may seem to be raising a savage weapon, perhaps a machete, above his head, but it is a performer's graceful step on a Paris stage and in Barthé's art. Its pedestal size makes it easy to admire the handling of bronze and the preternatural slimness better suited to a cabaret act than to a state of nature. Benga must have chosen his feral handle to reflect stereotypes of the black male, catering to them and playing against them, but there is little trace of African art or the "primitivism" that haunted Pablo Picasso. When it comes to Barthé, Modernism yes, irony no.

He looks rather sophisticated himself. Photos open the show with him and Alain Locke, a leading intellectual of the Harlem Renaissance, or actors playing the parts, dapper and dressed to the nines. They look much the same in archival footage of an exhibition opening packed with sophisticates. Isaac Julien,  who co-curated the new exhibition, came upon it while preparing for Once Again . . . (Statues Never Die), his video in the Whitney Biennial. Julien is claiming an ancestor for his own artistry and intellect and for African American art. He is also claiming an image of blackness that does not exclude gays like Barthé, Langston Hughes, Carl Van Vechten, and Julien himself.

who co-curated the new exhibition, came upon it while preparing for Once Again . . . (Statues Never Die), his video in the Whitney Biennial. Julien is claiming an ancestor for his own artistry and intellect and for African American art. He is also claiming an image of blackness that does not exclude gays like Barthé, Langston Hughes, Carl Van Vechten, and Julien himself.

He can easily find one in the sculptor's standing males like Benga. They are often sexualized and always in debt to European tradition, like Black Narcissus from 1929. You may remember Narcissus in myth as so in love with his image reflected in water that he drowns. Here he, too, is lithe and attractive, but also vulnerable. He could be pleading for love, like Julien's or yours. He holds what might be a cucumber or a penis.

Barthé wants his figures to be at once mythic and particular, in the present. Others include laborers, and the dualism continues in portrait heads. They extend his art to women, with enormous sympathy and with a Black Madonna as well. They may still border on precious, without the edge and complexity of greater artists or blackness in America. Sculpture in general can feel like a footnote to the Met's survey of the Harlem Renaissance, after paintings and photographs—and to Harlem's vitality in literature and music. For Julien, though, statues never die.

Locke contemplates them in his video at the Whitney, in an idealized setting—perhaps the Barnes Foundation, in dialogue with Albert C. Barnes. So, in entering the darkness, will you, only the sculpture may be hard to see. You may not even notice it beside Locke's firm but gentle gaze. Then, too, the new show opens not with sculpture, but rather those photos. Julien's version of history is fluid enough to limit its own impressive claims for the past. He calls the show "A New Day Is Coming," which speaks instead of the future.

That optimism infused the Harlem Renaissance. For Barthé, sculptures were studies in heroism, almost to his death in 1989. He called one work The Negro Looks Ahead. Still, he looked first and foremost not to the future, but to past and present. He tempts one to run one's hands over a head like a phrenologist or lover, to imagine a mind in full. It will not be the savage mind.

Nothing really changes

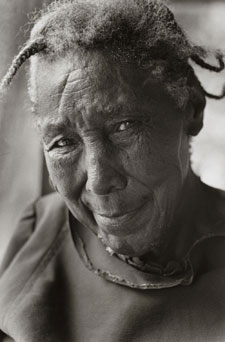

Daufuskie was never an enchanted island, no more than the Deep South. And yet for Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe it has become a heritage and a hidden treasure. Born in 1951, she published her series in 1981. Yet surely wedding parties still gather in their Sunday best in front of Union Baptist Church. Surely the bride still dresses in white, as does the bridesmaid walking discretely behind. Surely the men still fish in the warm air and turgid waters of the American South and still share their catch by boiling crabs. And surely Lavinia still smiles.

Or maybe not. Lavinia, known to anyone who cared as Blossum Robinson, was already getting on in years in 1979 when Moutoussamy-Ashe took her picture leaning so close to the camera that one could reach out and touch, and the community must have looked to her often for warmth and wisdom. The photographer began her visits to the island two years earlier and could hardly tear herself away. Still, everything comes to an end, and these are "The Last Gullah Islands." They became a book, displayed along with thirteen photographs in the floor for the Whitney's collection. It has a room to itself where Wanda Gág went on view last year, like an enclave from the fury and melancholy of America's cities and early modern art.

African Americans came early to the Gullah Islands, and they, too, came for freedom and comfort. Former slaves acquired property off the coast of South Carolina after the Civil War, and they could fairly be proud of it. Moutoussamy-Ashe has a fondness for creature comforts herself and did much of her work for mass magazines. One can recognize the pyramid of wedding guests from any number of photos of weddings, graduation ceremonies, and extended families. It suits a place where family and community must easily blend together. She could not resist shooting another wedding, in Central Park, on her return to New York—and, speaking of weddings, she married Arthur Ashe.

Much else, too, looks a tad conventional even in its modesty and misery. A ramshackle house and its windows barely hold onto a shutter or the wash on a line. "Aunt Tootsie" tends to her own wash while eying her children. A car with an impatient rider has blown out its windows, and a young woman leans up against a screen door that plunges her into near darkness. She becomes a study in introspection. Do I belong here, she might as well ask? Does anyone?

Still, not everything is magazine ready, and the questions keep coming. Moutoussamy-Ashe studied with Garry Winogrand, who knows the strangeness of people as much as anyone, and she became an AIDS activist when it counted most. Sometimes, too, convention does its job of keeping the past familiar. The Geechee islanders would have liked it that way. A boy carries the American flag at the head of a procession for graduation. Pride and patriotism belong to them, too.

Graduations, weddings, homes, and people—these are not portraits or events, but a way of life. It is not street photography where there are not all that many paved streets, and not documentary photography when nothing really changes. Is it trying too hard for human dignity? One could ask that about a lot of art right now, with its due celebration of diversity. Still, I can almost hear that smiling older woman, the folds in her clothes seeming to continue in her wrinkles. Dignity is fine, but it's me, Lavinia.

Isaac Julien ran at The Museum of Modern Art through September 28, 2024, Richmond Barthé at Michael Rosenfeld through July 26. Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art, through April 27, 2025. Related reviews take up Isaac Julien in 2013, the 2024 Whitney Biennial, and the Harlem Renaissance.