City of Dreams

John Haberin New York City

Jane Freilicher, Charles Mayton, and Martha Diamond

Jane Freilicher can come off as awfully light in weight, and why not? So can everything she paints. An artist of the postwar New York School, she has had less recognition than others, as is only fair. Yet she has her fans as well, as a bridge from tradition to other depictions of the city and its surroundings, then and now.

Consider just two, more than a generation apart, and the world of dreams. That realm can be so vivid and so familiar that you may wonder how you never noticed it before. Now if only you could pin down where you are. So it is, too, with the world for Charles Mayton, but the view out his window and on the ground is more than a dream. For that, you might have to go back to a city of nightmares, back in the dark, dirty, and delirious 1980s. For Martha Diamond, it was also a city of glass.

Light in weight and true to life

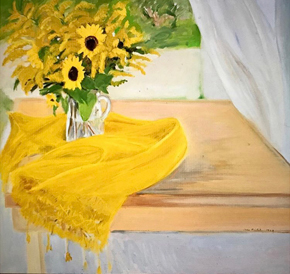

Lightness allows three fish on a plate to feel fresh enough to cook after nearly fifty years—and the flowers behind them to have just sprung to life. It allows a tablecloth to seem about to slip off the table while a drapery to its right lifts ever so slightly even in the indoor air. Still, it also allows one to take Jane Freilicher for granted or to dismiss her altogether as too much in the sun. Look again, though, at the view out the window for Amaryllis in the Evening from 1986. In the encroaching darkness, the city looks as grimy as in life. The bulb sharing its roots with a bright red flower is only about to bloom, but it might equally well have had its bloom cut off, leaving only its bare stalk.

Born in 1924, she came of age just as Abstract Expressionist New York was changing the locus and direction of modern art. She had a studio not far from the Eighth Street Club and the Cedar Bar, where Willem de Kooning ruled. The view out her window could extend to the clock tower on Union Square. She was closer, though, to the New York School of poets like John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, and Frank O'Hara, much like Joan Mitchell and Helen Frankenthaler. Just a year younger than Freilicher, Mitchell retained a glimpse of flora as well, even while extending the rigor of abstraction. Either way, we are talking avant-garde.

Freilicher is easy to like, because she made the avant-garde accessible, in her realism and her style. Afraid of the crowds in front of Sunflowers and Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh? You can always have her yellow flowers and New York evening. Besides, the grime of that painting wears off as one sticks with it, to the good. The darkening blue above red on the horizon parallels the blue skyline above red buildings closer to the picture plane. Red and white flashes from window after window add up to a quite a display.

She is more at home anyway in sunshine, between her sensibility and dependence on natural light. Like Mayton today, she was equally at home in city and country, and she kept a second studio on Long Island, in the Hamptons, until her death in 2014. She would face the window as she faced the easel, setting the table with her subjects beside a second for her paints. A shifting perspective allows her to look up at the still life while looking down on outdoors, placing them both in a flatter and more elusive space off the ground. The earliest in a selection of her paintings, from 1954, begins with her work table alone. If a classical nude intrudes into the skyline, it was just an object on the table, too.

Not that anything seems staged, adding to its freshness. Flowers all have their cheap and ordinary pots, with due attention to the soil. She need only move them onto the proper table along with a carafe from the pantry and fruit and veggies from the frig. They are all, as one title has it, "objects" and nothing more. If they never face the threat of decay in Flemish and Dutch still life from long ago, Freilicher is not a moralist. That connects her to the heart of postwar art after all.

Then, too, she was never one for whom death knocks. She was too busy enjoying the cloudless sky or the still brighter blue of an empty table. Her brush attends most to light and color, like the sheen off those fish. The paints in that early still life look solid, but after that she is less concerned for the thing itself or for paint as a reflection on itself. There is none of the broad, attention-getting brushwork of Alice Neel and Alfred Leslie or the photorealism of Philip Pearlstein. As with other realists among the abstract artists, Rackstraw Downes and, especially, Fairfield Porter, her flatness derives from her shifting point of view and her crispness from the light. If she remains light in weight by comparison, enjoy the light before it slips away.

A glimpse of liberty

Charles Mayton has his landmarks, like the Statue of Liberty, but you may have to look at least twice to spot her on the horizon. And then you may still wonder why you cannot place the street. Was South Brooklyn ever this colorful, and did its foliage ever have these particular colors? Its reds, yellows, and greens have a welcome intensity, and it seems not quite right to call them either natural or unnatural.  Daylight itself seems touched with the artificial glow of a city at night. Could that be why they call the neighborhood, 24/7, Sunset Park?

Daylight itself seems touched with the artificial glow of a city at night. Could that be why they call the neighborhood, 24/7, Sunset Park?

Mayton works in acrylic gouache on paper, the size of an ordinary letterhead, with a good thirty works grouped roughly by subject. He might have to paint that fast to catch the dream before it fades on waking. He works in the tradition of art since Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro and of works on paper, with quick dabs for leaves and seemingly unfinished brushwork for light. The same colors touch the sidewalk as one of those wifi and charging stations that are replacing pay phones beside it. Their peculiar geometry accords well with the sidewalk's grid, too. Neither seems to know enough to stick to proper squares and rectangles.

Of course, the appearance of speed may be a studied illusion. If these are casual sketches, they result from Mayton's practiced obsessions. He has tracked those wifi stations across more than a mile of Manhattan. (Would that they had come faster—and that the rest of those dirty and dysfunctional pay phones would just go away. Would, too, that their signal was half as fast as 4G.) Like Fifth Avenue here with more trees than I remember, everything for him has more than a touch of nature and a touch of the dream.

Every so often, something outright strange intrudes, like a large head more out of Giorgio Morandi or Giorgio de Chirico than life. More often, the semblance of a dream comes from simply observing. I shall take on faith that Mayton saw a harvest moon with bright yellow diffraction patterns pointing up and down, to the sky and to the moonlit ground. I shall take on faith, too, that the "melancholy pigeon" of a work's title landed on a ledge. If the location is hard to pin down, it ranges widely, to Berlin and upstate New York as well. As a late twentieth-century realist with even brighter colors, Freilicher shared that same stretch of Manhattan near Greenwich Village.

His one consistent subject is the glimpse. It might be a glimpse of the sky or the distant view past at the end of a dark street. It might be a glimpse of the kitchen at the end of a hall or of a house across the lawn, with the windowed walls of Modernism's classics. They are more brightly lit than the foreground and, depending on one's mood, more real or surreal. The glimpse never extends to signs of the artist's craft. The view out the window precludes a foreground table with anything that could mark the interior as his studio.

The gallery quotes praise for his work from Amy Sillman, another artist for whom almost anything can intrude—in her case, into abstraction. For both artists, things can come so fast that you may wonder if they are making progress. My own most consistent dream has me crossing half-familiar spaces in the vain hope of arriving anywhere at all. But then I am a freelance critic with twenty-five years of building a Web site and no expectations of fame. The best reward comes in a glimpse of something lasting and new. Mayton keeps looking for that, too, wherever it takes him.

City of glass

The 1980s were a scary time in New York, but not for Martha Diamond. In a haunted city, she was the one doing the haunting. Her paintings from the decade show the city in all its glorious and fearsome heights. A creature casts its shadow on a skyscraper almost as large as the building itself, and the narrowing from its shoulders to its head almost matches the tower's classic setbacks. If this is King Kong, he identifies with what he is about to destroy, and so does she. No wonder that, nearly forty years later, she has preserved what she saw instead.

Besides, the city that she saw has everything it takes to fight back. Sunlight on that tower has hardened into a harsh yellow that clashes happily with the shadow's spiky edges—and with the deep blue behind it of glass, steel, and the night. Diamond has the same contrasting colors the year before, in 1981, for the city in moonlight, only here yellow emerges through the windows from within. Elsewhere she drenches everything, tower and sky alike, in red or orange that makes them all the stranger. Towers may press close to the picture plane or to one another, all but swallowing whole the skyline's caverns. A point of view this high leaves no room for people and nowhere safe to stand.

Like the shadow, Diamond's New York is both inhuman and human enough, even without office workers and pedestrians. Back then, with crime rates at their peak in pretty much every city, people watched where they walked. There was more to fear in Times Square than costumed idiots selling the rights to pose with them in a selfie. For the young, though, like me just then discovering so many neighborhoods and so much art, it was liberating, not to mention affordable. It was like that for artists as well, including an artist from Queens, and one can feel her exuberance. She loves those forms and colors, and she lavishes them with paint.

The shadow's spiky hair? A mere artifact of a loaded brush. It seems that much more loaded in some twenty sketches in oil on Masonite, at most a foot to a side. Still, the works on canvas benefit from their scale, up to seven feet high. It allows them to immerse the viewer in their enigmatic spaces. Some approach abstraction, and I never could identify what looks like Venetian blinds but on an exterior, with something hanging to their left like clothing left out to dry or shrouds. Buildings may grow least familiar when Diamond sticks to white and blue for the gloss of glass and steel.

Others back then were turning their back on Modernism and abstraction, and she fits with that, too. New Image Painting had discovered landscape, with such artists as Jennifer Bartlett and Neil Jenney. Robert Longo had his Men in the Cities, Neo-Expressionism its brushwork, and Cindy Sherman her film noir. Irony was the order of the day. By those standards, Diamond may have seemed a little too playful and too eager to paint. If this was a dark city, where was the politics—from the money that darkened it to the AIDS crisis?

She seems more relevant now, with the resurgence of painting, most notably painting by women. Abstraction and representation get along just fine. Thanks to Covid-19, Times Square lay empty once more, perhaps even for Jane Dickson, and city streets felt haunted. In a New Yorker cartoon, Donald J. Trump is a monster like King Kong setting skyscrapers on fire. It is not too soon to return to what Paul Auster in his 2009 trilogy of novels called a city of glass. Diamond's White Glass is waiting.

Jane Freilicher ran at Paul Kasmin through March 13, 2021, Charles Mayton at David Lewis through February 27, and Martha Diamond at Magenta Plains through February 17.