The Flying Leap

John Haberin New York City

Yoko Ono, Charles Ray, and Conceptual Art

Robert Rauschenberg famously said that he works in the gap between art and life. Yet all art exists in the gap between physical object and human experience. That gap has a lot of room in it to play, and the result is changing games, styles, and interpretations. Art's leap of the imagination outraces even the promise of human flight. It becomes conceptual art.

Am I making excuses for what could do a better job of being art? If conceptual art is a slippery concept, so is art itself. It can embrace the material object or little more than words—a recipe for making that object. It covers all sorts of mind games, going back to one that did indeed hope to strike a blow against art, Dada. It returned to the confines of the gallery with Yoko Ono and Fluxus, before taking on a serious case of the cutes with Charles Ray.  But then just try to put a label on Ray's Whitney retrospective or, more than twenty years later, his growing air of importance at the Met.

But then just try to put a label on Ray's Whitney retrospective or, more than twenty years later, his growing air of importance at the Met.

Accepting fictions

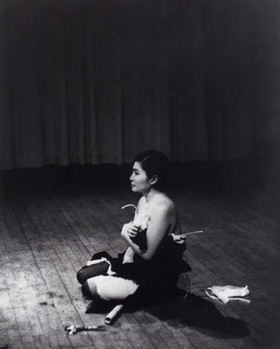

Another way to think of conceptual art is as hypothetical art, and elsewhere I have argued that almost all art begins with an artist willing to pose hypotheses as a way to question and to build on the past. Yoko Ono, for one, uses written directions to make people see outside a work's physical frame or reference points. In a long career too easily dismissed, she has refused esthetic distinctions in order to create beauty. Her exhibition requires a hypothetical leap simply to enter the room. In fact, I failed on my first attempt. I fell for a revolving door with no opening on the far side. I felt trapped by my mistakes, and I do not mean metaphorically.

At last I walked to the left, around the door, as if I literally had set the door aside. Alternatively, I could have used an opening to the right, the sort people put in their homes to let their dogs roam. (I recall, perhaps irrelevantly, that Ono made John Lennon act like a dog before reconciling with her.) It reminds me that J. L. Austin, the philosopher, spoke of performatives, of communication as action rather than text, and yet no one can predict the outcome of performance art. Accepting fictions includes getting hypotheses wrong.

When the Beatles were coming apart, fans projected the torment onto Yoko Ono. As a little kid I heard mostly about her primal screams. I have had trouble ever since understanding Lennon's meeting her—some years before Lennon and Ono collaborated on video. He described a show of hers as quietly liberating, a site of openness and exploration, and a pair of ladders like the one he climbed in an 2007 installation had much the same charm. If I had trouble fitting Lennon's silent experience into bad therapy as music, I had more trouble after Ono's previous New York show. There she displayed small, surprisingly elegant sculpture.

Her latest exhibition helps me get it together a little better. It also helps me reconstruct the sensibility of Fluxus, like another artist from Japan, Shigeko Kubota. For all the rhetoric and all the elegance, it encourages one to put one's preconceptions aside and take flight. The gallery wall warns that one may never be the same. If that preciousness, thankfully, never appears again, the theme becomes more and more haunting. Robert Rauschenberg in his combine paintings and collaborations would have understood.

Traditional frames for paintings are all over, but as still other doors. One is to be walked on, another to be looked through, another frames—or perhaps denies—the closure of a corner. The same room has inscriptions asking one to think past words like floor and ceiling. A work from the 1960s shows a mad kitchen, with appliances flying up into chaos. On the far side of a partition, a giant "magnet" pretends to explain it all. I thought of recent work by Hanne Darboven or Matt Mullican, who also create catalogs of experience.

Ono's sensibility has grown softer over time and more glib in its politics and reassurances, like an illustrated book without the illustrations. No wonder my favorite works are the oldest. In another, a short stepladder stands in front of a small, white panel bearing a single word, FLY. The handwriting looks casual, probably in pencil. I could have stepped on the ladder to take off, but the real flight comes from the casual landing of a speck on a painting. Go ahead and fly.

Reading the labels

Charles Ray illustrates the shifting idea of conceptual art. Even when his art relies on the object's uniqueness, its physical nature becomes a shorthand for multiple hypotheses, changing movements, and distinct leaps of the imagination. I could call him a Minimalist for his spare form. Yet Minimalism opens one's perception to changes in the environment, and Ray creates imperceptible changes. A motorized table spins infinitesimally slowly.  A rotating white disk is cut into a white wall.

A rotating white disk is cut into a white wall.

I could call his work at the Whitney anti-art, like Dada, but its provocations need the public space and coldness of a museum. Mannequins of parents and child stand in a row, hand in hand, as an ideal of the American family. But all are naked, and all are the same height. This child has grown far too fast for comfort. I could call it Fluxus, but it despises elegance and optimism. Like Luca Buvoli or Jonathan Schipper, Ray prefers casual clothing and an auto wreck.

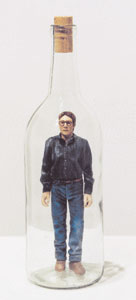

I could simply stick with the label conceptual art, much as for Thomas Schütte with his own statuesque realism, but Ray is a man of few words and provocatively real things. One row of sixteen photographs, a self-portrait, offers his "entire wardrobe," while a solid black cube holds potently smelling ink. A chair, bisected by a pane of glass, seems to float above the floor. The greater the pressure he places on himself and his art to vanish into words, the eerier an object's physical presence. If an object becomes art by an artist's statement, it becomes a stand-in for something as crudely real as a person. No wonder Marcel Duchamp needed to appropriate a urinal.

Conceptual art turns easily into cheap one-liners, and Ray's self-absorption hardly helps. Way too often, he comes off as no more than smirking, when I prefer art with an open grin. Trying to imagine the otherness of a homosexual, he creates a sculpture of himself, multiplied madly in body casts, screwing. He loves the coolness of it all. He revels in self-exposure and sexual provocation without a trace of pleasurable emotion. In practice, one walks past it quickly, along with most other rooms at his Whitney retrospective.

Yet Ray still breaks down distinctions, and he shows why the distinctions are so long overdue to break down. Often one's very real perceptions of the work hinge on a title. Through a title one learns about the ink, which one cannot smell or see. Another apparent cube has distorted one's perceptions of the entire room. 32 x 33 x 35 = 34 x 33 x 35 says so in its title, the aluminum cube's inner and out dimensions—and I believe it. So what if the math comes out wrong?

Overgrown children

Ray has a reputation for bringing grown-up pretensions down to earth. At his best, that includes his own. He did, after all, photograph himself draped limply over a plank pinning him to the wall. He could be a victim of John McCracken, the California Minimalist who churned out such planks, or of a career in art. He photographed himself, too, as little more than a shadow, bound up in a tree for the crows to peck at—should they be able to join the many predators who find their way into a gallery. He also photographed his wardrobe, and suffice it to say that he could just as well have crammed it all into a suitcase and abandoned it for all that art's fashionistas would care.

He may look halfway decent at the entrance to "Figure Ground" at the Met. But no, it is only a mannequin dolled up in a wig and his clothes, a dummy in more ways than one. He would be an empty suit if only he could afford a suit. Still, it turns out, he sees one segment of humanity as larger than life, kids, especially boys. The grown-ups in the room will not be pleased. That includes museum-goers and the rare adults in his art.

Ray has always toyed with scale, as part of his savvy and very material conceptual art. He also photographed himself trapped in a bottle, like a specimen for experiment. He modeled a seemingly ideal two-child family holding hands, for Family Romance in 1993, only the adults like the kids are stark naked. They are also the same size as the kids, because they have shrunk while the children have grown. The children have kept growing at that, to ridiculous proportions. Now if only the artist had not lost his sense of the ridiculous along the way.

He seems more than ever committed to the human figure, while now barely keeping his feet on the ground. One huge boy, visibly bored and ready for a day at the beach, is an archangel, whatever that means, in Japanese cedar. One can only presume that such stuff is precious. Others have a polished white or silvery finish, like Huck and Jim from an American classic. Jim does his best to act subservient while keeping an eye out, while Huck leans down to focus on himself. He could be a kid today preoccupied with his cell phone.

Now in his late sixties, has Ray, too, become overgrown child? He pulls out all his illusionism for a life-sized tractor, but it might as well be an overgrown boy toy. An aluminum relief copies Greco-Roman sculpture, because Ray is a proper artist at last. In a mere two rooms for mostly recent work, the show does have room for that family, along with a boy in overalls and the slow rotation of a circular incision in the museum wall from the years before. They might have made it here only because the boy is already getting up there in size, while the conceptual play with the wall is all but invisible. A white hand holds a white egg, next to the curled-up chicken it might have once contained, but which came first, the chicken or the egg? Maybe neither, since art begins in the serious artist's head.

I must leave a proper account to my past review of his 1997 Whitney retrospective, where I admired the mind games and illusions, while wondering whether they were not too clever by half. Now the mind and the illusion have taken a back seat to the cleverness. The Met would have you that Ray sculpts Huck and Jim because he, too, is an American classic, concerned for such highbrow notions as form, space, and time. Does that leave a mature artist out of touch with his times? A second sculpture takes up the moment in Huckleberry Finn when Huck disguises himself as a girl, but it seems unable to go anywhere near matters of fact, fiction, legend, or gender. I shall miss the paradox of conceptual art that refuses to lie.

Yoko Ono ran at Andre Emmerich through May 30, 1998, Charles Ray at The Whitney Museum of American Art through August 30. He returns at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through June 5, 2022. Related reviews and an interview with Edward Winkleman, the dealer, argue for the continued relevance of conceptual art as a kind of hypothetical art. Other reviews tackle some consummate conceptual artists, including Lawrence Weiner, Barbara Bloom, Eric Doeringer, and Dada. Related reviews also take up Yoko Ono in the 1960s and in 2015, with "The Riverbed."