Mister Althamer's Neighborhood

John Haberin New York City

Paweł Althamer and Maria Lassnig

If Paweł Althamer were any more well-meaning, the New Museum would kidnap passers-by on the Bowery and hold them hostage until they declare the profundity of his art, their common humanity, and their responsibility for the human condition. He is perilously close as it is—but his bodily obsessions have nothing on another self-portrait artists from Europe, Maria Lassnig.

Empty overcoats

Anyone entering in hope of a quiet respite from a brutal winter may need an attitude adjustment. You will have not have left behind New York's cold heart—or its persistent street musicians. One is always playing in the lobby, from among fifty in a changing cast over the course of the show.  They do not have hat in hand, but you may well think twice before stepping past. They also introduce the Polish artist's retrospective. The curators, Massimiliano Gioni and Gary Carrion-Murayari, call it "The Neighbors," but this is not Mister Roger's neighborhood.

They do not have hat in hand, but you may well think twice before stepping past. They also introduce the Polish artist's retrospective. The curators, Massimiliano Gioni and Gary Carrion-Murayari, call it "The Neighbors," but this is not Mister Roger's neighborhood.

Upstairs recruits from more than seventy community groups cover the fourth floor with art of their own devising. You may join in, but be prepared to don a white lab coat and to play well with others. On opening morning they had already filled much of the walls and floor. The doodles, in mostly black and white, have less in common with the exuberance of New York street art or its borrowings in Raymond Saunders than with William Kentridge in South Africa. A tepee at the cavernous room's center adds a further political message, should any be needed. The museum describes the work's incarnations, since the 2012 Berlin Biennial, as "dimensions variable," and do not even ask about quality.

The background music has a name, The Musicians, labeling it firmly a work of art. For Pawel Althamer, art is necessarily collaboration and performance, even when it is by his own hand. It both draws on the community and promises to create one on a harsh and lonely planet, but very much on his terms. It is idealistic, but like the graffiti seriously in need of editing. It can approach cliché even at its most sincere, much as street musicians lean to familiar melodies. At least three galleries in the last few months alone have now asked people to pick up a pen to lend a hand.

The clichés take on a more visible shape a floor below, with sculpture from as far back as 1991, and so does the existential anxiety. Here art runs to the social engagement, hyperrealism, and outright kitsch of John Ahearn or Duane Hanson. Althamer and his daughter stand naked, like remnants of the last human tribe on earth. His sculpture's hemp and animal intestines allude, he explains, to "rural Polish traditions." Other life-size characters, created in collaboration with children, "celebrate" society's cast-offs—in one case, to be displayed near the subject's favorite bar. Even a more expressionist portrait, in metal, takes on a glaring literalism once one learns that the woman has multiple sclerosis.

The closer art comes to the artist's life, the more its naturalism gives way to sentiment. He poses as a goat after his travels to Mali and Brazil—and because it reminds him of a popular cartoon character. An ambitious landscape, seen before at the New Museum in "After Nature," moves from Soviet-style block apartments and barbed wire to rowboats on a mirrored lake. In an accompanying video, in collaboration with Paulina Antoniewicz and Jacek Taszakowski, Althamer stares forlornly through an apartment window in his undershirt, while a child fends off tears. An only slightly wrier and darker sculpture represented a seated "observer," perhaps you, but with nothing beneath its heavy clothing. As Groucho Marx says, "I'm going back in the closet, where men . . . are empty overcoats."

Althamer even makes art out of his lack of editing, in So-Called Waves and Other Phenomena of the Mind, a video collaboration with Artur Zmijewski. Monitors scattered around the show's final floor follow him as he ingests various mind-altering substances "on a journey to explore the depths of his own mind." It apparently does not run all that deep. He tastes bark from a tree and pronounces it "ruins of a city." He looks inward as "all thoughts drift away . . . vanish . . . peace." One may fairly wonder how much thinking went on in the first place.

Mission accomplished

"Let the journey begin," he exclaims, as if in a lost episode of Star Trek, but for museum visitors it will almost have ended. Still, they will have shared an entire floor with Althamer's largest work, even compared to a monster coming up this summer in Socrates Sculpture Park. His most anxious and maybe his most human, Venetians approaches the expressionism of Thomas Houseago or Magdelena Abakanovich. The fifty standing figures do not acknowledge the videos, the visitor, or one another, even when close to touching. Their gaunt plastic shapes, cast from extruded ribbons, resemble bare skeletons or rags. Still, there is no escaping having seen this act before, and of course one face lost in the crowd is the artist's.

When it comes to bombast and sentiment, he has plenty of company. In the lobby gallery, Laure Prouvost builds a rambling shack "just for you." It has a love poem among the notes on its front and two $1 bills on the floor inside, almost enough to afford a cup a coffee. The French artist, now based in London, adds video to let you know that "this art will touch you" and "you'll be rich in your soul." A monster and designer handbags here and there suggest at least a small degree of irony, like a less confessional Sophie Calle, and "at night the water turns black." Still, as a slim, mature woman strummed a pop tune out front thanks to Althamer, I wanted her to be Prouvost and to be singing just for me.

Up in the education department, European politics gives way to order, community, and fantasy. tranzit, "a network of autonomous but interconnected groups" all the way from Austria to Slovakia, remodels the architecture as a spaceship, based on sci-fi films from the Cold War era. "Report on the Construction of a Spaceship Module" means to explore Communism's futuristic visions, but it seems altogether at home. Contributors speak on video from a spacious interior closer to Stanley Kubrick than to Gravity. Further inside, shelves hold a good hundred more works of art, one less memorable than the next. A thrift shop should be this clean and orderly, but then art should look less like a thrift shop.

Zmijewski himself exhibited in New York in 2010, along with Hans Haacke at the short-lived X-Initiative. He described Europe in the present as the site of violently competing protests and interviewed an Auschwitz survivor. He might have documented the potential for human cruelty—or staged it. And that ambiguity is bound to haunt art about the recent past, as both memory and creative act. Political art demands honesty, even as art relies on making things up. There is no one answer.

As recently as 2011, the New Museum presented artists struggling with memories of the Eastern Bloc and with disappointments since its dissolution, and it will do so again in 2016 with Anri Sala. "Ostalgie" did not go so far as nostalgia for the old order. Yet art offers its own promise of freedom that can so easily go unfulfilled. With Althamer, that promise mostly does, but there is no easy way out—not when facing the reality of his homeland or the Bowery. All one can ask is that he not sugar-coat it. Too often, his puppet theater comes a little too close to Mister Roger's after all.

A true New Yorker will know anxiety, existential or not. A New Yorker, too, will understand an artist who does not just live out of a suitcase, but turns one into his studio—and Althamer does, in miniature, seated inside and sadder than ever. He also extends his commitment to actual neighbors so easily forgotten on the gentrifying Lower East Side, the Bowery Mission. Anyone who donates a men's coat gets free admission, not a bad idea for the New Museum in perpetuity. Still, from New York to the far side of the Iron Curtain, Althamer's confessions and community have a way of effacing particulars, much as Venetians carries over from the 2013 Venice Biennale. Political art may take agony and empathy, as Mister Rogers would surely understand, but it may not survive whimsy.

Inside-out

Her subject is portraiture, but not everyone's idea of realism. The sitters face mostly forward, at almost full length, but they can rarely be troubled to stand erect. At times one can hardly distinguish sitting from lying down. The same colors that supply their contours also serve as shadow, in unfinished brushstrokes against an undefined background. The brightness has something to do with sunlight, but here sensation goes well beyond direct observation. One might be looking out or within.

I might be talking about Alice Neel, Mira Schor, or, at a quite different extreme, Paula Modersohn-Becker, the German Expressionist. I mean, though, another woman who presided over the last century, with her own academicism and anxiety. Born in 1919, Maria Lassnig studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, where a teacher compared her to Rembrandt, praise that she was desperate to overcome. She left, via Paris, for New York—the city, she has said, of "strong women"—returning in 1980 to Austria, where her heart had never left.  And this woman worries about internal organs: "the only true things . . . transpire within the house of my body.

And this woman worries about internal organs: "the only true things . . . transpire within the house of my body.

She means her naked body. One can forget how often portraiture for German Expressionism, too, meant self-portraiture, but Lassnig remembers. (The Neue Galerie devotes nearly a full room of its survey of "degenerate art" under the Nazis to the subject.) She has virtually a single subject, except now and again for prosthetic limbs or a straitjacket. When she empties out the background, it is for her body in snow. When a child appears with her, at least one of the two is deformed or dead.

Lassnig's self-consciousness can grow suffocating in even a concise retrospective, at MoMA PS1, and weighty titles like I Bear Responsibility approach self-parody. Her obsessive self-involvement comes as a natural follow-up to Mike Kelley, another troubled soul who has had the run of a blue-chip Chelsea gallery or two—and another sign that the alternative space now belongs fully to MoMA, for which an emerging artist can be in her nineties or already dead. Yet her career turns out to track much of late Modernism, with each step bringing her closer to herself. Already in 1945, as the Red Army neared Vienna, a self-portrait discards Rembrandt for her sharper palette and wider brush. In the 1950s she tries abstraction, first with black curves like those of early Al Held, then with wide-open color fields out of Helen Frankenthaler. However, the Austrian created those marks with her naked self.

Yves Klein, too, had female models execute paintings by rolling on them, but she is after not performance but visual and tactile sensation. She reappears again in the 1970s—as Lacoön (in antiquity, the Trojan priest dragged to his death by snakes), a monster, and covered with plastic wrap. She adopts heavier flesh tones in the 1990s, like her Rainbow Selves. She also finds creepy parallels in popular culture, like a cartoon thought balloon emptied of words. Finally come the gathering whites and sprawling poses of her last ten years. An artist with seventy years of work behind her was very much alive to see her retrospective happen, although she died May 6 in Vienna.

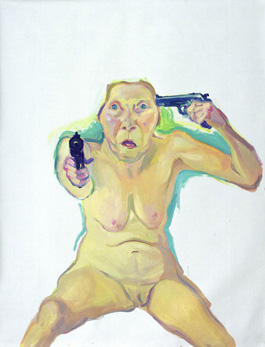

To the end, she is still "drawn by death"—the title of a double self-portrait with a head to one side and brush in hand to the other. She also makes explicit her double view without and within. It includes her brain slipping outside her skull. It also has her holding two guns, one pointed toward the visitor and one held to her head. Lassnig's art is not exactly a circular firing squad, but it does not permit of escape, most especially not by her. Hold a gun to my head, and I may admit at times to enjoying it.

Paweł Althamer, Laure Prouvost, and tranzit ran at the New Museum through April 13, 2014, Maria Lassnig at MoMA PS1 through September 7.